The Water Lily Paintings: Claude Monet’s Gift to the Nation

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

A hundred years ago in Paris a piece of paper was signed which left us all a wonderful legacy. For in 1922 Claude Monet agreed to give the Nymphéas, the series of enormous paintings known collectively as The Water Lilies, to the French nation. Today they remain on display in the Orangerie, a museum in the Jardin des Tuileries, housed in two huge oval rooms specifically adapted to Monet’s own design. The “refuge for peaceful meditation” he wanted to create remains exactly that today and the story of it came about is uplifting and poignant in equal measure.

Jardin des Tuileries. Photo credit: Dennis Jarvis / Wikimedia Commons

“I am good for nothing,” wrote Monet, “other than painting and gardening” and these twin obsessions run right through his work, seen most especially in the many canvases he painted in his garden in Giverny. Monet rented the house there in 1883, later buying it, and was still living there when he died in 1926. He loved its orchard and the surrounding landscape, he adapted the barn to be his studio, and, above all, he devoted his energies to the garden. He devised the layout and the plantings, choosing “a flower palette to look at all year round, always present, but always changing,” as the critic Arsène Alexandre wrote after visiting.

Monet’s Garden at Giverny, 1895, Wikimedia Commons

In 1893 he bought a little extra land, a water meadow, enlarging it by another purchase a few years later, and created the pond, which is so familiar from his paintings, planting first white water lilies which grew locally and then buying imported ones to increase the color range. Soon, there were clusters of lily pads on the water and weeping willows, iris and bamboo growing around the edges, and it was into this idyll that he brought his easels, setting them all around the pond in order to paint the beauty he had created. For more than 30 years this was one of his main subjects, and he created at least 300 paintings of the pond, some 40 of which were on giant canvases. “These water landscapes,” he wrote in 1908, “have become an obsession.”

Monet’s waterlily garden in Giverny, Creative Commons

By 1908 he had been working for several years towards an exhibition to be called Les Nymphéas (The Water Lilies), painting for long hours on most days, always to his own exacting standards; in fact the exhibition had been postponed a number of times because he threw away many canvases which he found unsatisfactory. Eventually, in May 1909 there were over 40 pieces he was pleased to include and the exhibition proved a great success. The public loved his water lilies, the delicate flowers, the vibrant colors, the watery setting with all its different light effects and rippling movements. The critics were also enthusiastic, one noting Monet’s “completely new, fluid and somewhat audacious style of painting in which the water-lily pond became the point of departure for an almost abstract art.”

Claude Monet, The Water Lily Pond, 1897, Public Domain

By January 1915, when Monet was already 75, he wrote of his plans to create a “Grande Décoration,” a major project which would revolve around “water, water lilies, plants, spread over a huge surface” and one which would occupy him for much of the last 10 years of his life. He told friends that despite his age, this was something he felt he just had to do: “These landscapes of water and reflection have become an obsession for me. It is beyond my strength as an old man, and yet I want to render what I feel.”

Claude Monet, The Water Lily Pond, 1900, Public Domain

At this time, Monet had been through a number of personal difficulties. The deaths of his second wife Alice in 1911 and of his elder son Jean in 1914 had left him deeply depressed and at the same time he began to develop the cataracts which were to plague him for the rest of his life. He was profoundly affected by the war, especially worried for his younger son, Michel, who was fighting at the front. Gunfire could sometimes be heard in Giverny and many of his neighbors fled to safety, but Monet’s response was to stay and dedicate himself to his work. He often rose at 4 a.m. and worked until early evening, explaining “It’s the best way to avoid thinking of these sad times.”

Alice Hoschedé in the garden, Claude Monet, 1881, Wikimedia Common

Monet had served in Algeria in 1860, before being sent home with typhoid, and so he had an understanding of conflict. Although no one could have expected an elderly man to go to war, he nevertheless said he was ashamed to be working on his paintings “while so many people are suffering and dying for us.” But then he realized what it was that he could do. The day after the armistice of 1918, he wrote to his friend, the Prime Minister Georges Clémenceau and offered to give two of his Grandes Décorations, now nearing completion, to the nation “to honor the victory and the peace.”

Clémenceau, delighted to accept Monet’s offer, suggested that as the two works being offered were part of a cycle of eight, they should all be displayed together. Monet agreed and signed the paintings over in April 1922 but requested that they should be housed in their own setting, rather than at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs as originally planned. So began a to-and-fro which lasted until the artist’s death in 1926. Monet’s stipulations included being able to oversee the arrangements for their display and also being allowed to keep the paintings until he died. He continued to make alterations and improvements, probably because of his perfectionist approach, but also perhaps due to a reluctance to part with the pieces. However, Monet kept his promise, and the canvases were moved into their home in the Orangerie in 1927, less than a year after he died.

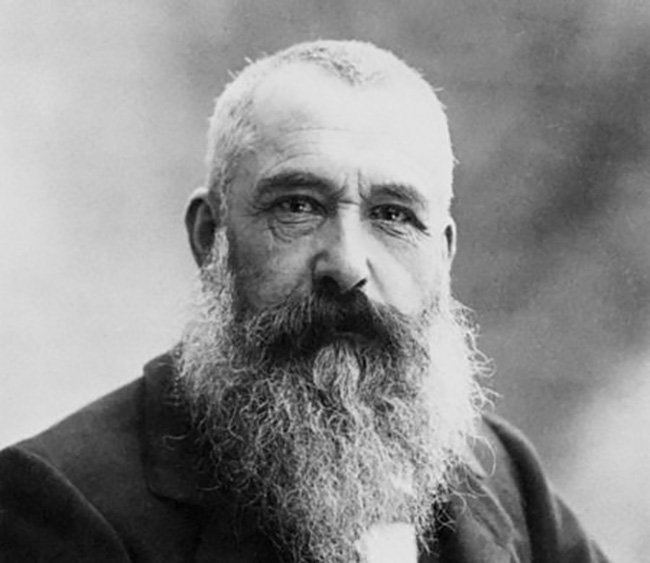

Portrait photograph of the French impressionist painter Claude Monet by Nadar, 1899, Wikimedia Commons

Monet’s reaction needs to be understood in the light of the difficulties he experienced in his last years. By 1923 he was nearly blind in both eyes because of his cataracts, and he agreed to undergo surgery, something he had resisted until then. The improvements in his sight meant he wanted to go back over some of his paintings and redo sections. Also, he was at an age when he had lost many of those he loved, including all of his Impressionist colleagues. He attended the funeral of Degas in 1917 and that of Renoir two years later, writing on that occasion that “with him goes a part of my own life.” So, the Nymphéas are both the culmination of a lifetime’s work and an expression of the feelings of an elderly man in declining health whose life had been tinged by sadness many times.

Monet’s legacy is immeasurable and includes all his paintings and his house and garden at Giverny which were donated by his son to the Institute of France. But here at the Orangerie is something very special, the gift he himself gave France, eight of his loveliest paintings displayed just exactly as he wanted them to be. You can lose yourself in their vastness – some 200 square meters of canvas! – and reflect on their beauty and their poignancy, and on the way, they combine this hugely talented man’s two great passions, painting and gardening. You are, as the artist André Masson once wrote, in “the Sistine Chapel of Impressionism.”

Details

Musée de l’Orangerie

Jardin des Tuileries, 1st arrondissement

Tel: +33 (0)1-44-50-43-00

Ticket price is €12.50. It’s recommended to buy tickets online in advance for a certain time slot.

Hours: 9 a.m. – 6 p.m. Closed Tuesdays.

Lead photo credit : Claude Monet, Les Nymphéas, Soleil couchant, Creative Commons

More in Claude Monet, Iconic French Painter, Impressionist art, Monet, Musée de l’Orangerie, Nympheas by Monet, Water Lily