The Richest French Artist of the 19th Century, Unknown Today

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Ernest Meissonier and Édouard Manet were contemporaries whose works showcase a revolution in art

The richest and most popular artist in France in the 19th century wasn’t Renoir, Monet or even Manet, but an artist whose reputation languishes in obscurity. Ernest Meissonier, born 1815, was a Realist painter who would end up as a footnote to the history of French painting when the free-hand of the Impressionism took over from the painstaking minutiae of Meissonier.

Meissonier was a self-taught artist who started his career with small, meticulously detailed book illustrations. It was this exacting detail that would make Meissonier‘s name; it would also be the ruin of him. He enjoyed incredible success in his lifetime. He first showed his art at the prestigious Paris Salon at the tender age of 19.

Ernest Meissonier, Autoportrait. © Wikipedia, Public Domain

His paintings harked back to the Revolutionary and Empire periods. He often portrayed masculine scenes of derring-do against a backdrop of 17th and 18th-century life. He also developed a military genre capturing Emperor Napoleon and his descendant Napoleon III on their respective battlefields. Meissonier was twice elected as the President of the Académie des Beaux-Arts and the first artist to receive the Grand-Croix in the Légion d’honneur.

Meissonier’s small paintings relied on scrupulous research and close work with models whether they be horses or humans. When he didn’t have a live horse to work from he would recreate one, out of wire, wax, and leather. He dressed his studio models from his personal collection of armor and 18th-century costumes, with collars and cuffs suitable for gentlemen and musketeers. He would spend all his daylight hours creating wonders of precision and meticulousness.

The Judgement of Paris. © Ross King.

As early as the 1840s Meissonier’s works prompted effusive reviews. Ross King quotes in his 2006 book, “The Judgement of Paris: The Revolutionary Decade that Gave the World Impressionism,” an anecdote that said “each year at the Paris Salon… the space before Meissonier’s paintings grew so thick with spectators that a special policeman was needed to regulate the wealthy connoisseurs as they pressed forward to inspect his latest success.”

Meissonier’s micro work commanded macro prices. Members of the social elite, like the Rothschilds, vied for them. Napoleon III bought a painting called The Brawl for 25,000 francs, which was, according to Ross King, eight times the salary of an average factory worker in 1855. Another commission for Napoleon III resulted in a fee of 85,000 francs.

Ernest Meissonier, The brawl. © Wikipedia, Public Domain

In 1846 Meissonier purchased his Grande Maison in Poissy. His success afforded him a stable for eight horses and a coach house for his fleet of very expensive carriages which bore the crest Omnia Labor – “Everything by work”. He had a duck pond and a greenhouse to supply his English garden which sloped down to the Seine where his two yachts were moored. His house boasted two large studios – one for summer and one for winter. He also maintained a Paris apartment in the rue des Pyramides.

Meissonier’s maison in Poissy. Photo credit: Philippe/ (c) Région Ile-de-France – Inventaire général du patrimoine culturel

The most unconventional feature at the Poissy manor was Meissonier’s miniature railway. He had a track installed with a small carriage that was pushed to and fro by a couple of unlucky workers while the painter jotted down every motion and strain of the horse galloping alongside his hurtling carriage.

Not everyone loved him. In 1848 the famed artist Delacroix visited Meissonier in his studio to see him working on the heart-rending painting The Barricade, rue de la Mortellerie. Delacroix said, “His faithfulness of representation is horrible, missing the indefinable thing that makes it art rather than reportage.”

Ernest Meissonier, The Barricade, rue de la Mortellerie, juin 1848. © Wikipedia, Public Domain

To create his great work, Napoleon III at Solferino, shown at the 1863 Salon, Meissonier had received a commission in 1859 from the government to illustrate several scenes from the campaign. Meissonier was actually embroiled in the action and made numerous on-the-spot sketches, but he spent more than three years researching the 30” x 17” painting. He interviewed survivors at the scene. He became an expert on all aspects of Napoleon’s life. He rummaged through flea markets for appropriate costumes. He spent months deciding on the most miniscule of detail. Absolutely nothing was left to the imagination. “Perfection,” Meissonier said “lures me on”

In response to an era of rapid technological changes there had been a surge in nostalgia. “My house and my temperament belong to another age.” Ross King wrote that Meissonier did not feel at home in the 19th century. He detested the trappings of the industrial age; cast iron bridges and modern architecture threw him off. Even modern fashions like frock coats and top hats rubbed him the wrong way.

By 1863 Meissonier was the wealthiest and most celebrated painter, not just in France, but the world. However, critics found it absurd that in the modern age of telegraphs and steam locomotives, painters relied on scenes from the past. Poet and art critic Charles Baudelaire launched a call for artists to embrace “la modernité” in his treatise “The Painter of Modern Life.’

And then came Manet. Seventeen years younger than Meissonier, Édouard Manet worked and lived in the Batignolles district of Paris, a neighborhood just bohemian enough for an artist. Manet befriended Baudelaire and paid heed to his call for painters to be of their time.

Edouard Manet, Luncheon on the grass. © Wikipedia, Public Domain

Manet wore frock coat and top hat, too modern for Meissonier. While Meissonier was pugnacious-looking somewhat arrogant, Manet was described as having a sunny soul. Handsome and outgoing, Manet personified charm. The son of a judge, Manet was raised as a gentleman in the neighbourhood of Faubourg Saint-Germain at 5 rue Bonaparte (then 5 rue Petits-Augustins), across from the École des Beaux-Arts. Disenchanted by law school and the navy, Manet trained to be an artist, studying for six years in the studio of Thomas Couture. Sons of judges did not become painters. But Manet did.

5 rue Bonaparte in Paris. Photo credit: Jmgobet/ Wikimedia commons

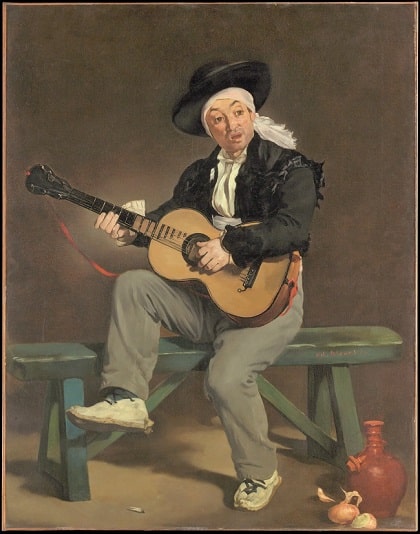

While Meissonier showed at the Paris Salon at age of 19, Manet was 27 years old when he felt ready to launch his public career at the Paris Salon of 1859. The jury for the Salon promptly rejected the work. In 1861 he entered the strange new painting for the time, The Spanish Singer. It was roasted by the critics, but it was awarded the Salon’s Honorable Mention. Though he had yet to sell a single painting, he seemed to have finally arrived.

Edouard Manet, The Spanish singer. © Wikipedia, Public Domain

The pioneers of modern painting, like Manet, Monet, and Renoir often worked en plein air, capturing fleeting images from their summer gardens, or impressions of leisure at clubs, cafés or riverside settings. Famed art dealer Ambroise Vollard, on a sojourn to Meissonier’s house, saw his students raking the studio floor with sparkling white rice powder where they arranged miniature cannons, little trees, ammunition wagons, soldiers and horses to imitate a winter battle.

Vollard’s companion ventured, “(Claude) Monet can only paint from nature.” Meissonier scoffed, “Don’t talk to me of your Monet and all the gang of jeunes. The other day I saw a picture by someone called Besnard in which there were violet colored horses. Let us talk seriously.”

Ernest Meissonier, Napoléon III à la bataille de Solférino, Musées du Second Empire, Château de Compiègne. Public domain.

While Meissonier was toiling away on his Solferino painting, Manet began work on a masterpiece his own – Le Bain aka Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe. Despite the measured success he’d had with the Spanish Singer, this did not guarantee an entrée into the Salon. The lofty figure in charge of the Paris Salon, Comte Nieuwerkerke, thought it his duty to guard and protect French art. He did not like Manet’s work. He wanted to encourage history painting and discouraged gritty realism. Manet was rejected.

On May 3rd, 1863 the Salon opened with Napoleon III at the Battle of Solferino as one of the big draws of the exhibition. Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe was relegated to the Salon des Refusés, a separate exhibition for those painters of merit who had been rejected by the officials. It sparked controversy. The nude woman, who directly regarded the viewer from Manet’s most famous canvas, clearly belonged to a contemporary Paris. To an audience used to the aristocratic fashions of yore from Meissonier’s work, she was vulgar. In the 19th century, art nudes were always appreciated, but only if they represented goddesses and heroines.

Ernest Meissonier, 1807, Friedland. © Wikipedia, Public Domain

Another horse painting by Meissonier contrasted with one in Manet’s pre-Impressionist style. From 1861-75, Meissonier Friedland – evoking one of Napoleon I’s greatest victories – required more than 14 years of work from 1861-75. It was one of the most anticipated paintings in the history of art. Meissonier was a reputed painter of horses and considered himself quite an expert in this matter. Did it chafe Meissonier that Manet could knock off some preliminary sketches of horses in an afternoon? Manet’s Races at Longchamp (1866) showed horses galloping straight at the viewer. Manet did not make detailed drawings of his subjects before painting them.

Edouard Manet, Races at Longchamp. © Wikipedia, Public Domain

Manet wasn’t obsessed with perspective or capturing three dimensions. Half his Longchamp painting was sky; the crowd just dabs of paint in the background. Manet gave the rapid impression of flying forelegs kicking up a cloud of dirt which was the opposite of Meissonier’s carefully rendered, lifelike beasts. There was a marked difference between a painter who captured the sensation of speed through slurred colors and the man who used a railway track to faithfully convey the same motion.

Before 1870 there was no evidence to confirm these polar opposites had ever met. As both the men’s names started with the letter M, their works would be unavoidably displayed in the same room at the Salon. Between 1864 and 1870 Meissonier had sat on at least four juries of the Salon which rejected four of Manet’s paintings.

The two had a number of friends in common including Delacroix and Daubigny. Therefore Meissonier was well-aware of Manet as an artist. In December 1870, in the midst of the action of the Franco-Prussian War, Manet was transferred to the staff headquarters where he was in the company of commanding officer Meissonier. The artists pretended not to know each other.

Manet’s Le Bon Bock of 1873 gave him unaccustomed celebrity. A typographical error led to a “Bon Bock” craze with reproductions of the painting sold in bookshops and tobacconists. A newspaper said that an offer of 120,000 francs had been made for Manet’s painting of a pot-bellied drinker. This was an incredible sum – one that only Meissonier alone could command. Manet himself went into the newspaper offices demanding to know what madman would pay that kind of money for one of his paintings. The printer had added one too many zeros.

After the success of the 1873 Salon, Manet sold paintings worth 22,000 francs. Claude Monet was able to command 24,000 francs. In 1874, the Impressionists exhibiting at Nadar’s studio were now the pioneer painters of the future and their godfather was Manet. Many critics and writers thought Manet was the future of French art.

Ernest Meissonier, 1814, La Campagne de France. © Wikipedia, Public Domain

In 1890, the year before his death, Meissonier was offered 850,000 francs for one painting- more than the whole budget of the Paris Opera. The Campaign of France was the most expensive painting purchased in the 19th century. But what it came down to was not who made the most money; it was their artistic vision – what artists put on their canvases and how they saw the world. There was a struggle between those artists firmly glued to the past and those of la vie moderne that led to a revolution in painting.

Meissonier was not a painter of modern life as Baudelaire had so poignantly pleaded; he was a painter of the past. He was obsessed with his own posthumous reputation. Meissonier once wrote, “Time gives every human being his true value.” Critic Théophile Thoré had no doubt that Meissonier would be consecrated for future generations.

Today it is Manet’s works that command exorbitant prices and keep museum admissions ticking. Manet’s works endure while Meissonier’s works gather dust. Manet died in 1883. Within months a retrospective exhibition of his work was launched at l’École des Beaux-Arts and was met with the kind of favorable reviews that Manet did not often receive in his lifetime.

Meissonier died at the top of his game but within a decade his reputation and prices had plummeted. Meissonier’s home and studio were sold within two years of his death. Academics started treating his legacy with disdain. Meissonier went from being one of the most revered painters in Europe to a national embarrassment. His every excruciating detail became a target for future generations. He himself said “many people who had great reputations are nothing but burst balloons now.”

Lead photo credit : Ernest Meissonier. © Wikipedia, Public Domain

More in artists, Ernest Meissonier, Impressionist art, Manet, Monet, painting, Realism, Renoir

REPLY