On the Trail of Heroic Impressionist Gustave Caillebotte

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

“Who knows M. Caillebotte? Where does M. Caillebotte come from? In what school was M. Caillebotte trained? Nobody has been able to inform me. All I know is M. Caillebotte is one of the most original painters who has come to light for several years and I don’t fear compromising myself by predicting he will be famous before long.”

Since art critic Marius Chaumelin said these words in April of 1876, the pieces of Monsieur Gustave Caillebotte’s life have fallen into place and we can follow Caillebotte’s path throughout Paris and the circle of the Impressionists.

Gustave Caillebotte was born August 19, 1848 into an upwardly mobile family that would soon become very rich. Caillebotte would spend the first 20 years of his life at 160 rue du Faubourg-Saint-Denis (later renumbered as 152). The building was demolished when the rue des Deux-Gares was built straight through their lot. The Caillebottes made their money in textiles and were contracted to supply the French army with camp beds. They augmented their wealth by investing in real estate during the redevelopment of Paris in the 1860s.

Les jardiniers (1875) Private collection. Photo credit © Gustave Caillebotte -, Wikipedia. Public domain

Young Caillebotte was a bit of a dilettante and because of careful investing by his father and the subsequent deaths of his father, stepmother and brother, he became a millionaire by the age of 30. He earned his degree in law by 1870. He was with the National Guard – the Seine Garde Mobile – during the Franco-Prussian war up until 1871. He joined the art studio of Jean Bonnat in 1872 and passed the entrance exam to the École des Beaux-Arts in 1873 when he was 25. His attendance there was short lived. He felt constrained by academic teaching and was soon drawn to what would be known as Impressionism.

Then why label him heroic? Caillebotte organized the Impressionist exhibitions, paid for the publication of advertising, collected art from the painters, paid their rent, tried to calm their squabbles, and provided food and board. He bought his colleagues art and left a huge collection of Impressionist art to the State under a very specific stipulation. Without Caillebotte’s influence, the world would be left with a weaker form of Impressionism than that which endures today.

Caillebotte featured both modern, urban subjects from unusual Parisian vantage points and his bucolic surroundings on the Yerres river. Caillebotte’s paintings display his great sensitivity to light and the violet of his atmospheric shadows is incomparable. Demonstrations of masculinity seemed more important to him than painting pretty women, but on the other hand, some years he just painted food, or flowers or portraits. He loved the contrast of light and dark interiors and what lay outside his window frames. Many of Caillebotte’s pictures have an aura of peace and solitude as if his subjects were absorbed in a dream, turned either in on oneself or outward to a spectacle.

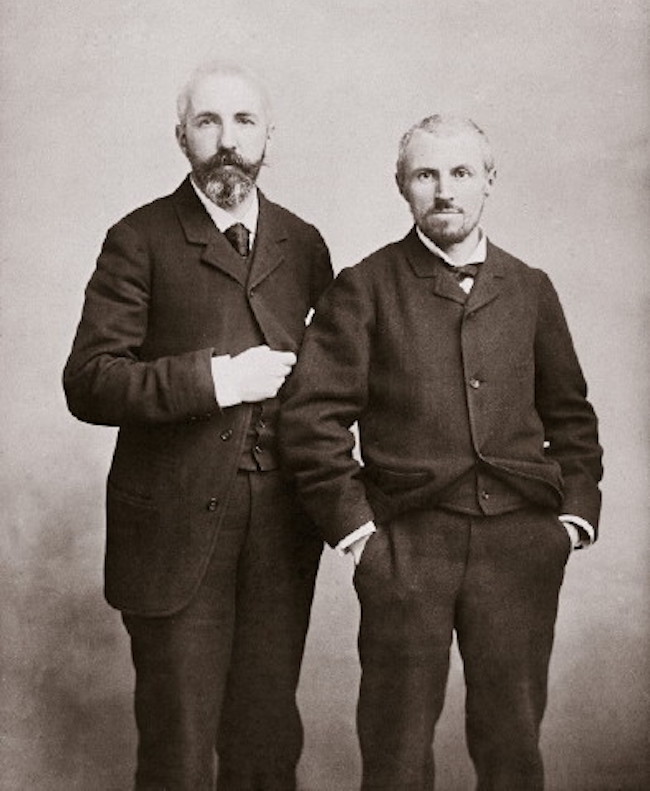

Gustave Caillebotte (right) and his brother, Martial. Author unknown, Wikipedia. Public domain

In 1873 Caillebotte was introduced to Claude Monet. He met Edgar Degas in 1874 who urged him to take part in the first exhibition of Society of Independent Artists. They met at the house of mutual friend Giuseppe de Nittis at La Jonchère, on the banks of the Seine, between Rueil-Malmaison and Bougival. However, at that time Caillebotte was not swayed.

In 1875 Caillebotte painted some canvases that would seal his artistic reputation. A major success was The Floor Strippers, showing three men carrying out work at his home at 77 rue de Miromesnil, his new house at the corner of rue Lisbonne, where he lived with his brother and mother. The Floor Strippers was part of Caillebotte’s submission to the 1876 Exhibition.

Another important 1875 painting originating from the same address was Young Man at His Window. The man, his brother Martial, stands at the threshold between light and dark. Experts have concluded that the woman Martial Caillebotte is watching is heading onto Boulevard Malesherbes and have determined that it portrays the afternoon light coming from the west as the viewer is facing north. Caillebotte’s streets and scenes would often capture the same quiet emptiness that is exhibited here.

The same calm is captured in the 1875 painting The Yerres, Rain. The Yerres river ran along side the Caillebotte estate in the town of Yerres, 20 km southeast of Paris, at 8 rue de Concy. The location was used often by Caillebotte showing the rowers, fishers and swimmers on the river. Caillebotte’s focus on the water’s surface is unusual for the time, forecasting the lily pads of Monet with whom he became close friends.

The artist’s younger brother in the home on rue de Miromesnil (1875). By Gustave Caillebotte

In 1876 Caillebotte was introduced into the second exhibition of Independent Artists by Monet and Renoir; the term Impressionism would not be adopted until the following year. Held at 11 rue le Peletier at the Durand-Ruel Gallery, Caillebotte showed eight paintings at the event; his work, including The Floor Strippers, stole the show making the Impressionists’ second exhibition more popular than the first.

Le Pont de l’Europe that Caillebotte exhibited at Durand-Ruel’s in 1876 was a masterpiece of geometry, celebrating the then modern engineering feats of Baron Haussmann’s redevelopment of Paris. It spanned the station and sheds at Gare Saint-Lazare linking the new neighborhoods on both sides of the station’s sunken tracks. The length of the bridge on which the unmatched couple walk is the rue de Vienne. The top-hatted man is based on Caillebotte, as much a flâneur as his subject. This viewpoint can be readily seen today but the nature of the grids and girders has changed completely.

The same year Caillebotte exhibited Le Déjeuner showing lunch with family at Yerres. This portrayal is an airless display of bourgeoisie life and like many of Caillebotte’s paintings, permeated with silence. Despite the table set properly with Baccarat crystal, fancy silver tureens and ivory-handled knives, the light coming through the curtains indicates it might be more enjoyable outside. This table setting is recreated at Property Caillebotte at Yerres.

Caillebotte and his brother Martial settled into a Paris apartment at 31 Boulevard Haussmann just behind the new Opéra and looking what is now the Galeries Lafayette. Caillebotte felt his vision renewed in this renovated area of the city. His new apartment was higher, just below the servants’ quarters, where he would paint striking geometric urban views.

In January 1877 Caillebotte invited Degas, Manet, Monet, Pissarro, Renoir and Sisley to his apartment to discuss plans for the Third Impressionist Exhibition. At this dinner party a policy emerged, not just to display the artists’ works but also to establish a coherent style. This policy accentuated the rivalries within the group which led to arguments. One such argument broke out at the Impressionist hangout, La Nouvelle Athènes at 9 Place Pigalle, where Caillebotte accused Degas of “spreading disunity into our midst,” blaming him for attempting to pack the group with artists Caillebotte thought unworthy.

Caillebotte largely organized the Third Impressionist Exhibition himself. He used his personal wealth to provide crucial financial support for his fellow artists. He paid for the advertising and paid the rent for the exhibition space at 6 rue Peletier. In 1877 Caillebotte helped Monet rent a flat across from the Gare Saint-Lazare in order for Monet to paint his famous steam train pictures.

That year Caillebotte exhibited Paris Street: Rainy Day representing the intersection of the rue de Turin and the rue de Moscou. The famous rainy day couple is walking south on rue de Turin and the corner is still Instagrammable.

Paris Street, Rainy Day (1877), Art Institute of Chicago, Gustave Caillebotte. Photo credit © Gustave Caillebotte, Wikipedia. Public domain

At his rural location in Yerres, Caillebotte painted Les Canotiers on his beloved river. This 1877 paintings bring us into an insider’s view point. We’re perching on Caillebotte’s seat and brought into the activity.

In 1878 Caillebotte painted Roofs In the Snow, showing the dramatic view from his building over the older, lower roofs below. From his aerie under the eaves on Boulevard Haussmann, Caillebotte painted La Rue Halevy, Seen From the 6th Floor. In 2019 this painting was for sale at Sotheby’s for an estimated 6- 8 million. This is one of Caillebotte’s few paintings that captures the hustle and bustle of Paris streets compared to the usual abandoned hush he usually portrayed.

Caillebotte exhibited at the Fourth Impressionist Exhibition in 1879, at 28 Avenue de l’Opéra – again taking control of the presentation. Monet did not want to appear but Caillebotte collected his works and hung them. Cezanne, Morisot, Renoir and Sisley did not participate in the exhibition; they were still stinging from the discord Degas had sown. However at the exhibition’s close Caillebotte reported that there had been 15,400 admissions and all expenses had been covered. Each member received 440 francs. A satirical cartoonist of the time said that Caillebotte had used his wealth to save the Impressionists from foundering and dubbed him as their leader.

In Renoir’s 1879 Oarsmen at Chatou the artist himself says that the rower holding his skiff taut is inviting Caillebotte for a ride. In 1879 Caillebotte paints his self-portrait in front of Moulin de la Galette bought in 1877 from Renoir.

At the Fifth Impressionist Exhibition in 1880 Caillebotte exhibited 18 paintings. One of them, The Interior, features a woman at his window. She exhibits ennui despite her comfortable surroundings and her eye, and ours, is drawn to the letters NT RBU on the building across the street. It is indeed the Hotel Canterbury at 44 Boulevard Haussmann, now the Galeries Lafayette.

In 1880 Caillebotte bought a house with splendid gardens at Le Petit-Gennevilliers, just across the Seine from Argenteuil, which became his main residence. Caillebotte owned a variety of sailing yachts with names like Le Roastbeef, (sic) Condor, Ines, White Ass and Grasshopper whose race results were entered into the records of Parisian yachting. Caillebotte had a passion for sailing and is often described as a naval engineer. In reality, along with naval engineer Maurice Chevreux, he designed sailboats for himself and other amateurs. He was skilled at this and spent more time designing yachts than painting. A replica of Le Roastbeef was built in the 1990s. In the 1880s the silk sails of Caillebotte’s yachts featured the outline of a cat.

Artistically, the most memorable thing Caillebotte did in 1880 was to pose for his friend Renoir’s Luncheon of the Boating Party at the Maison Fournaise on the Île de Chatou. In Renoir’s ensemble cast Caillebotte is the man in the foreground with the white undershirt and straw hat.

In 1881 Caillebotte boycotted the Impressionist’s Sixth Exhibition along with Cezanne, Monet, Renoir, and Sisley citing that Realistic tendencies were infiltrating the Impressionist’s exhibitions and putting the onus on Degas. That year Caillebotte tried his hand at still-lifes, painting mostly food like fruit, cakes, seafood, and meat. This is quite a departure for Caillebotte who, until 1881, painted mostly contemporary life in Paris or en plein air studies in the summer visits to his property at Yerres.

In 1882 the seventh exhibition of the Impressionists was held at the Salon du Panorama de Reichshoffen at 251 rue Saint-Honoré in a building designed by architect of the Opèra, Charles Garnier. Today it is the site of the Mandarin Oriental. Caillebotte framed and helped to hang the art for the event. Caillebotte came in for a lot of ridicule at this show. One critic thought his works hilarious. Eugène Renoir, Pierre-Auguste’s brother, in a letter to his wife, described Caillebotte’s works as “some very boring figures done in blue ink, some excellent small landscapes in pastel.”

Caillebotte took little part in Parisian artistic life after 1882. He was disillusioned with the arguments that resulted in the break up of the Impressionist group. Caillebotte amassed most of his art collection before 1880. After 1882, the last year he exhibited with the Impressionists, he added nothing to his collection.

He settled down to his life at Le Petit-Gennevilliers where Caillebotte kept a cook, a maid, her two children and two sailors. Caillebotte became an avid gardener. As is obvious from his paintings of the time, Caillebotte lavished a lot of care on his grounds. In 1883 Renoir visited Caillebotte at Le Petit-Gennevilliers and painted a portrait of his lady friend Charlotte Berthier who was also part of the household. Caillebotte never married Berthier but she lived with him from 1883 until his death. In 1883 he added Charlotte to his will, giving her a life annuity.

Edouard Manet – The Balcony. Photo credit © Google Art Project Wikimedia

According to Claude Monet’s stepson, Monet got his first taste of grand gardens from Caillebotte which inspired his own garden at Giverny. Unfortunately the quay-side property was taken over just a year after Caillebotte’s death as a shipbuilders yard and is today home to a sprawling aerospace engine manufacturer.

In 1884, at the Hotel Druot auction of the works of the recently deceased Manet, Caillebotte paid 3,000 francs for The Balcony, one of Manet’s most famous paintings. In 1885 Caillebotte was named godfather of Renoir’s first born son, Pierre. As Le Petit-Gennevilliers was on the same stretch of the Seine as Argenteuil, Caillebotte tried his hand at painting the same sites Monet and Renoir had. Caillebotte made no attempt to capture the same leisure or nature in these landscapes that other artists had painted. Instead he focused on the architecture of the train bridges and the factories in the far distance. This would be perhaps a foreshadowing of what would happen on his stretch of the Seine.

On May 27th 1888, Vincent Van Gogh wrote to his brother, “My dear Theo, I read an announcement in L’Intransigeant that there’s going to be an exhibition of the Impressionists at Durand-Ruel — there’ll be some works by Caillebotte — I’ve never seen anything of his, and wanted to ask you to write and tell me what they’re like— there are certainly other noteworthy things, too.”

The announcement that Van Gogh read was for an exhibition of paintings at the Durand-Ruel Gallery, 11 rue Le Peletier.

In 1888 Caillebotte was elected town councillor of Gennevilliers. He often paid for the town’s expenses out of his own pocket. He kept in touch with his Parisian artist friends. There were dinners at the Café Riche from 1880-1894 at 16 boulevard des Italiens. Sometimes arguments erupted between Renoir and Caillebotte. Renoir would taunt Caillebotte who could easily anger. In 1922 journalist Gustave Geffroy would write about those evenings at the Café Riche. “The discussions sometimes got quite heated, especially between Renoir and Caillebotte. Renoir with a mirthful irony, took a mischievous delight in taunting Caillebotte, a choleric and irascible man, whose face would change color, from red, to puce, to even black whenever his words were contradicted by the sprightly flow of words which Renoir loved to employ against him.” Café Riche was replaced by an Art Deco bank in 1927 which is now itself under renovation.

The boulevard des Italiens in Paris (France) and the café Riche, circa 1890. Photo credit © author unknown, Wikipedia. Public domain

After 1884 Caillebotte worked on portraiture and largely concentrated on the activity on the Seine by Le Petit-Gennevilliers. In 1892 Caillebotte painted his most famous self-portrait. Caillebotte produced a total of 565 works as the 1994 edition of Marie Berthault’s catalogue attests. Caillebotte died in Le Petit-Gennevilliers in February 1894 at the age of 45 from what we would today understand as a stroke or an aneurism. Were his red-faced episodes at the Café Riche an indicator of what was to come?

He bequeathed his collection to the French state as per his 1876 will. Renoir was the executor of the will drawn up when he was just 28. Due to Caillebotte’s generosity toward his fellow artists, he accumulated an astonishing collection of Impressionist works, which eventually consisted of 19 Pissarros, 14 Monets, 10 Renoirs, nine Sisleys, seven Degas, five Cezannes and four Manets. He stipulated that his collection “should go neither to an attic, nor a provincial museum, but straight to the Luxembourg (the museum devoted to living artists) and later to the Louvre.” But there were years of controversy that Renoir and Caillebotte’s brother Martial had to endure revolving around what the government was willing to take and what the Louvre was willing to show. There were cries from the other artist of favoritism, some even suggesting that a moral turpitude would descend on society. Eventually in January 1895 it was agreed that the Musée de Luxembourg should accept only those pictures which it could hang. The remaining 29 pictures were left in the hands of Martial who offered them again unsuccessfully to the government in 1904 and 1908. Ironically in 1928 the government expressed a desire to have them Martial’s widow rejected the term of the bequest.

Gustave Caillebotte with the Shepherdess dog on the Place du Carrousel, 1892. Photo credit © Martial Caillebotte, Wikipedia

Lead photo credit : Caillebotte in his greenhouse (February 1892), Petit Gennevilliers. Author unknown, Wikipedia commons

More in Claude Monet, Gustave Caillebotte, Impressionism, Manet, Yerres River

REPLY