French Tarot, Anyone? Historian Ronan Farrell Shares Insights

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

During these extraordinarily uncertain and anxiety-provoking times, who has not consulted some form of predictive practice? Maybe, for you, it’s the daily weather forecast. Or maybe something more “alternative.” Confess. Is it your daily horoscope online or your deck of Tarots?

For those of you who are fans of or just curious about Tarot cards, here is an interview with a brilliant Tarot expert, Ronan Farrell, whose blog Traditional Tarot offers an enormous collection of texts on the subject, originally written in French and now available, thanks to Farrell’s extraordinary talents as a translator, in English.

Ronan Farrell and I met through an email exchange. Farrell contacted my colleague Professor Jacqueline Gojard, University of Paris III (Sorbonne nouvelle), who is the leading André Salmon expert in the world. She forwarded his email to me. This introduction focused on a blog post about the poet, critic, journalist, and novelist André Salmon, whose poems about Tarot cards were published in Action, January 1921 (this is the 100th anniversary!).

But before we get into all that, allow me to introduce the gifted and generous Mr. Farrell, who recently completed his Master’s degree in Buddhism in Taiwan.

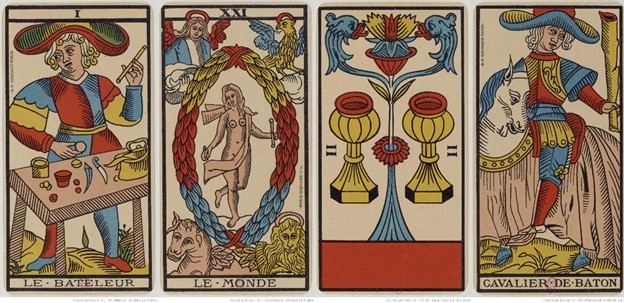

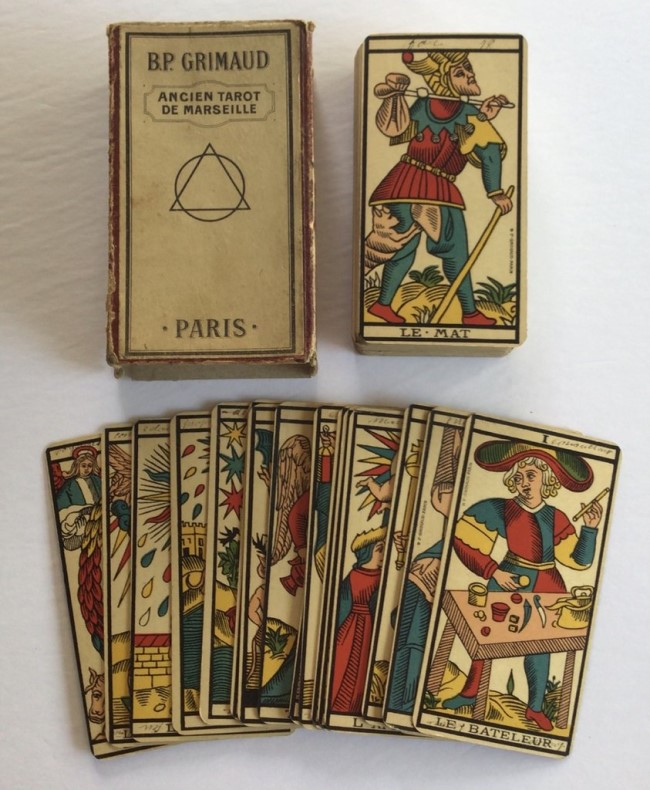

Grimaud Tarot de Marseille, c. 1930, courtesy of the BNF

Beth Gersh-Nesic: Hello, Ronan, welcome to Bonjour Paris. We are eager to hear about the history of Tarot cards and related subjects. But first, please tell us about you. Where are you from exactly? What got you started on this odyssey through Tarot history? And why?

Ronan Farrell: Hello Beth. To be honest, I was never very good at introducing myself, but here goes: I am from the west of Ireland, and am of French descent on my mother’s side, which explains my facility for that language.

“Odyssey” is, as we say in French, “un bien grand mot“! It strikes me that giving an answer in reverse chronological order might be more direct, so in a nutshell, the three-step answer to the question is as follows: Initially, I had set up a blog to use as a notepad to keep track of some texts and images I came across, as well as bits and pieces I’d translated for friends and correspondents, and I had left it on private mode for a few years until it struck me that I might publish some of these pieces and give readers an inkling of the variety and quality of the material written in French that remains more or less unknown in English. That was the proximate cause, I suppose.

Some years ago, I’d become intrigued by the entire phenomenon of Tarot – not only the images on the cards themselves, but their origins, real or imagined, and all of the varying and more or less inventive interpretations put forth by a host of authors over the course of the past few centuries. As a result, I began to read up on the subject, making notes, simply out of personal interest.

Of course, there is a bit more to it than that. When I was quite young, perhaps 10 or 12 years old, I remember seeing a pack of Tarot cards for the very first time in a small supermarket in a grimy north Paris neighborhood, where I was visiting a relative. It was at the check-out counter, next to the cigarettes, matches, batteries, chewing gum, all those last-minute impulse-buy items, and I clearly recall the impression that the gaudily-colored medieval-looking figures produced at the time. I managed to scrape together enough pocket money to buy a pack discreetly, and would look at the images, wondering what they were supposed to mean, and how they were supposed to tell the future. The accompanying booklet was not particularly useful in that regard for my 12-year-old self, perhaps something we will return to, and so I put them away in a drawer out of a sense of frustration at not being able to pierce their mystery. It must be said that at the time I knew absolutely nothing at all about the cards, nor even anything of the pop culture surrounding them. I’d grown up in a house without a television, but full of books, and it was simply something I’d no idea about, other than that it was a vaguely mysterious and typically French thing, as the name suggested: Tarot de Marseille. On holidays in France, I’d often seen people playing the game of Tarot, but they used the Tarot Nouveau deck, a pack of larger-sized playing cards with an extra suit of trumps depicting scenes of everyday 19th-century life, and certainly not nearly as intriguing as the crudely carved woodblock prints of the Marseille Tarot. So, the pack of cards lay in a drawer for years, and every now and then I’d take it out and look at it and ponder the meaning of it all, without understanding much more to it than that.

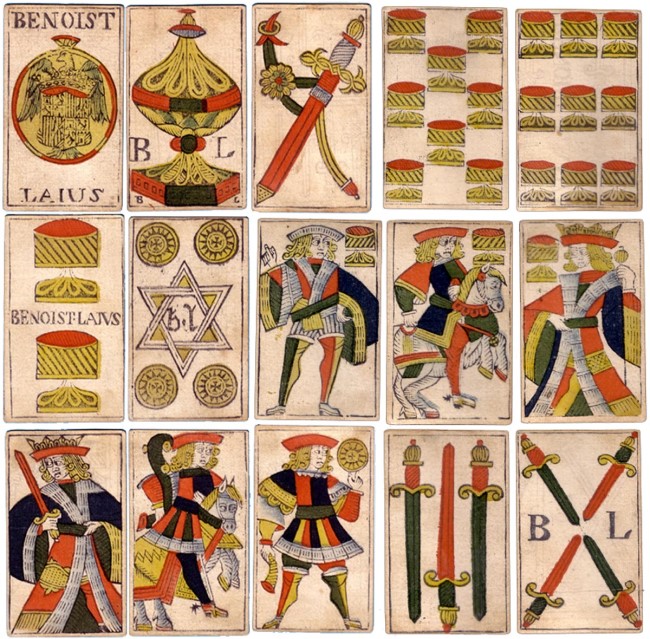

Benoist Laius (Montpellier), 1706-1738.

BGN: So if I understand you correctly, you bought the Marseille deck, read through the little paper brochure inside the box with the cards (that’s in my deck), and then you never bothered to buy a book to learn how to set up the spreads and read the cards? That is quite unusual. My sister and I shared the Marseille deck and learned about reading the cards. So, finding out your fortune from the cards didn’t interest you at first?

RF: Not quite. The “little white booklet” was not so little – almost 100 pages – and it had nothing at all either about history, or the meaning of the cards, or fortune-telling. Instead, it was full of philosophy, psychology, physics, and what we would now call “consciousness studies.” Extremely interesting, to be sure, but very dense and I could not make head or tail of it for a long time.

Sometime later, again in France, I found a book somewhere that gave all the usual fortune-telling meanings of the cards, but also all manner of correspondences with the letters of the alphabet, numbers, the days of the week, even herbs, crystals and metals, without providing any explanation or justification for doing so. Perhaps I am too analytical, but it all seemed very arbitrary to me, and not very useful in the end, so I set that aside too.

Eventually, I revisited the little booklet, written by one Tchalaï, an odd name with no surname, and attempted to once again figure it out. But while the ideas involved had gradually become clearer to me in the meantime, I still had little understanding of what the Tarot was, and what it did. Or perhaps, what it was supposed to be and do. There too, I set it aside, until I later developed a more historical interest in the subject.

Again, my interest was not and is not fortune-telling, although what that consists of is a fluid notion, and an interesting topic in itself. Initially, I knew practically nothing at all about the cards, and that included this idea that they could be used to divine the future, I was simply intrigued by the images.

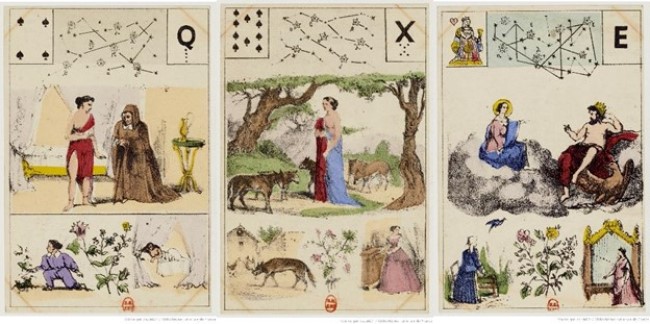

Grand jeu de Mlle Lenormand, late 19th century, courtesy of the BNF.

BGN: Then you became interested in the history of the cards, which is fascinating. When did you start this research?

RF: That started a little later, perhaps some 12 or 15 years ago or so. I think it was a case of being sufficiently intrigued over the years to decide to dive in, but also from having gained a greater awareness of the presence of things like Tarot in literature and culture more generally that set me off on that course. So I started to read up on the subject, some of the standard French works mostly and historical reference works, and art history and so on, and found that it was a very interesting subject, not necessarily because of the mystique of the whole thing or the symbolism of the images, but simply because it touches upon so many different domains of human activity: art, iconography, the invention of printing and the transmission of playing cards from Asia to the West, the relations between games and divination, gambling, religion and the law, debates about high culture and popular culture, and many other things.

BGN: Your blog introduction dated April 19, 2014, provides a wonderful overview of your mission as a historian and translator of texts on Tarot. Your next blog post was on March 19, 2020, during the pandemic lockdown. Did your decision to open your posts to the public have anything to do with the pandemic?

RF: Yes and no. I had begun to revisit Tchalaï’s writings – the author of the little booklet alluded to earlier – and had translated a chapter for a friend some years ago, and later, I’d posted some excerpts online since her ideas were completely unknown in English. Eventually, I felt it would really warrant a proper book proposal, so between researching and translating that, I thought I may as well open up my blog and make things more presentable and accessible. The timing was more or less coincidental, but the lockdown did help, in a way, as I was able to get more material organized and translated than I might otherwise have done. Conversely, I figured that if I was spending so much time at my computer then presumably others were too, and that reading some of these weird and wonderful writings might provide a welcome distraction.

BGN: Should we call you a “tarologist”?

RF: Ha! Honestly, I have never asked myself the question. “Amateur” in all senses of the word, perhaps? As a term, in French “tarologie” is typically used in distinction to “taromancie” – i.e. divination with Tarot cards. Tarology perhaps involves a broader emphasis on gaining greater self-knowledge or self-awareness by using the cards. But the Tarot itself is an inanimate object – a pack of pieces of colored cardboard: it is the people – those who question and those who read the cards – who live, think, speak and act. How they think about and see the cards, how they use them for some purpose or other, or to help them decide on a course of action, I think, is worth examining. It does sound a bit anthropological, but at the end of the day, the Tarot is a human creation and reflects human concerns.

Playing the Tarot card game in France (Public Domain: Wikipedia)

BGN: When were Tarot cards invented? When did they arrive in France?

RF: Tarot cards appeared in northern Italy in the mid-15th century, around 1440. Playing cards had already been around for a few decades by then, having been imported from the Middle East and North Africa to Spain and Italy along the trade routes. What happened in Italy is that a deck of cards comprising four suits became welded to a set of allegorical images known as trionfi, or “triumphs,” from which our English word “trumps” comes from. The genesis of the process is unclear, but similar sets of allegorical emblems on cards used for pedagogical purposes from a slightly later date exist, and I tend to think that perhaps a number of these were added to the playing cards in order to provide what we would now call a suit of permanent trumps, and to increase the relative complexity of the game. It must be noted that the card game of Tarot is a trick-taking game, similar to bridge and whist in that respect.

The issue of why these images were chosen, and whether the trump sequence has a particular significance are questions which have given rise to a lot of speculation. It may well be the case that there is no innate mystery at all, and that they were simply chosen from a stock of commonly understood allegorical emblems current at the time. In any case, the earliest decks were luxury items created for the aristocratic families of the day, before being mass-produced by woodblock printing, or copperplate engravings.

Tarot cards entered France sometime in the early 16th century, most likely brought back by soldiers returning from the French wars in Italy. The earliest reference we have to Tarot in French is in Rabelais’s famous novel Gargantua in 1534, tellingly enough. Two and half centuries later, towards the end of the 1700s, Tarot would become inextricably linked to theories of its mysterious and supposedly Egyptian origins, as well as to fortune-telling…

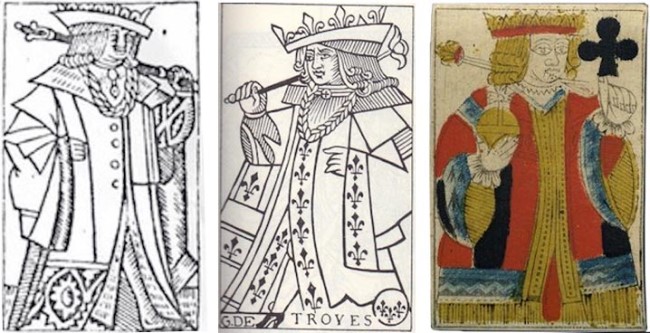

Richard Bouvier, 17th century

BGN: Thank you for bringing up the history of Tarot as a card game before it became a popular divinatory art, and thank you so much for bringing up Egypt. I have been told that Tarot cards go all the back to ancient Egypt. How did this idea come about? Do we know the source?

RF: Tarot cards don’t go all the way back to ancient Egypt; this is one of those ideas that came into being a few years before the French Revolution and grew legs! In fact, we can date the birth of fortune-telling with Tarot cards to more or less the same time, at least, that is when things really took off, under the impetus of this new “ancient” mystical pedigree. The person responsible for floating this idea was an eccentric savant, Court de Gébelin, who wrote a massive work of comparative mythology and philology which includes a chapter on Tarot. The theory was then taken up by a fortune-teller who styled himself “Etteilla,” his name spelled backwards, and who then spread the idea even further. This all occurred against a backdrop of what is known as “Egyptomania,” very much a cultural trend at the time, and this is one example that still survives down to the present day, although we are – or ought to be – much clearer on the accepted history by now.

BGN: Your blog highlights the artists and writers who used Tarot in their creative process. Please tell us about a few of these artists. I am particularly intrigued with the Fauve artist André Derain’s deck, which you have on your blog.

How did he use these cards? Or did he create the deck as an artistic project?

RF: Derain had an abiding interest in mysticism, and his notebooks bear witness to that. I think it would be fair to call him a “seeker.” We know that he read the cards himself, since André Breton mentions this. But apart from his brief poetical piece, he doesn’t seem to have written anything else on the topic. He did create a set of Tarot-like woodblock prints for an edition of Rabelais’s Pantagruel, and the ballet costumes he designed for La Boutique fantasque (1919) are also inspired by the cards, but I haven’t come across signs that he drew his own deck, which would be interesting to discover. The set of cards which illustrate the journal which included Derain’s Tarot piece come from a deck that dates back to the early 19th century, although I don’t know if it belonged to Derain himself. I think that it is also fair to say that he had both a practical and theoretical interest in the cards, in addition to being visually inspired by them for some of his work.

BGN: And which writers used Tarot for their creative practice?

RF: Italo Calvino’s Castle of Crossed Destinies needs no introduction, since it is probably the best-known work inspired by Tarot. But truth be told, there is a tremendous amount of literature out there, especially French, which uses the Tarot as a narrative device rather than as a mere mystical prop. I think we can say that the Tarot as a creative instrument goes back at least to authors like Gérard de Nerval, who was inspired by its imagery, or the Symbolist Paul Adam, who read the cards for his characters to determine their fates and the plots of his novels! These techniques are now so common as to be found in mainstream books on creative writing, but it is, in my view, the direct result of the set of overlapping circles between games, divination and storytelling: They all posit a world, and its constituent elements, which can be combined together to form all manner of situations and possibilities. In fact, the relation between Tarot and literature goes back almost to the inception of the game in Italy, since there was a genre of poems about Tarot, and also a literary parlor game which had the players improvise verse according to the cards they drew. The poet Aretino wrote a poem based on Tarot cards in 1521, and 500 years later, its creative power is unabated.

A novel such as Michel Tournier’s Vendredi ou les Limbes du Pacifique (Friday, or, The Other Island) is the classic example of a novel where a Tarot reading “telegraphs” the plot, which then unfolds in an unexpected manner. There are many other examples of this narrative device. But less obvious are the books in which the Tarot itself does not make an explicit appearance, but contributes somehow to the structure, or the plot, or otherwise acts as a creative ferment: Robbe-Grillet’s Les Gommes (The Erasers), Jeanne Hyvrard’s La Meurtritude (Waterweed in the Wash-Houses), and other works by Michel Butor, Pierre-Jean Jouve, and so on. Antonin Artaud’s Nouvelles Révélations de l’Être is also largely based on his reading of the Tarot, and another remarkable work I have come across recently is the poetic science-fiction novel by Charles Dobzynski, Taromancie. If anything, the sheer breadth of Tarot-inspired works shows that, as a creative stimulant, the literary use of the Tarot defies classification.

BGN: When you mentioned “the classic example of a novel where a Tarot reading telegraphs the plot,” I thought of Prosper Mérimée’s novella Carmen (1845) which introduces the central character reading Tarot cards for the author who tells the story. Georges Bizet, Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy’s adaptation of the novella for the opera in 1875, telegraphs the tragic conclusion in Carmen’s reading of her Tarot cards at the beginning of Act II. In your Salmon blog post you demonstrate the use of Tarots in poetry.

Georges de la Tour, The Cheater with an Ace of Diamonds, 1635, Musée du Louvre (Public Domain: Wikipedia)

RF: Yes, that’s right. I had translated Salmon’s Cartomancy poems in the summer of 2020, but held off on publishing my translations for a few months as I wasn’t completely satisfied with the presentation. Eventually, I felt the new year was the perfect time to publish something rather different to what I’d done before and so put it out. But there’s always the question of broken links and new material appearing and so on, so I went back and checked and saw that Salmon’s works were still in copyright, which I hadn’t noticed the first time round. I then wrote to Jacqueline to mention my rendition of these poems, and she referred me to you. But I had found her email address on your Salmon website to begin with – so it was all very circular!

A. Camoin and Company, Marseille, c. 1890

BGN: Then we began to correspond about Salmon’s Tarot poems and his book Le Voyage au Pays des Voyants, which you read too. I re-read the book after we started to write to each other. And at that time, I had just discovered another website that translated Salmon’s Tarot poems. Do you know why Salmon wrote these poems? Your reference to the parlor games that required composing a poem about a Tarot card by drawing from the deck sounds like a possibility.

RF: To be honest, the background to Salmon’s poems is still a little obscure. My knowledge of the milieu, and of Salmon and his work in particular, is somewhat lacking, but my understanding of the Cartomancy poems is that they are the result of a number of different strands coming together: Salmon’s account of his visits to the fortune-tellers shows that he had a lasting interest in the divinatory phenomenon, and was well acquainted with its procedures, both from his investigations, but also from his friendship with Max Jacob whose interest in the conjectural sciences is well-known. Salmon does not appear to have been either a “believer” or a “practitioner” of these arts but comes across as more of an “informed but skeptical layman.”

BGN: That’s the journalist hat that Salmon wore to earn income.

RF: Some of the early Italian Tarot poems would have been accessible to Salmon as they are mentioned in the standard historical works available at the time in French, and it is possible that he read one of those for his research. In this type of game, a poem was spontaneously composed to describe a person or group of people, using the attributes of the Tarot cards. Interestingly, these parlor games using the cards became increasingly elaborate as the cards themselves became more widely available and developed into a sort of allusive theatrical performance played in aristocratic circles.

As to whether there is a more formal or even ludic aspect to the composition of the Cartomancy poems, I cannot say; as far as I know, Salmon’s memoirs are silent on the matter, but it is a tempting possibility. After all, the cryptic (or not-so-cryptic) cartomantic definitions provide a ready-made source of material for the poet; and these gnomic sentences, blended to the historic and cultural baggage of the playing cards – the kings, queens and jacks as historical or semi-legendary figures, with their own attributes and personalities – are so much symbolic fodder to be worked and reworked into a thematic set of poems.

André Perrocet (Lyons, late 15th-early 16th centuries), King of Clubs, c. 1491-1524

BGN: Now I wonder if Salmon’s poems started out as a casual studio challenge, like other games played among the members of Picasso’s Gang. Derain belonged to Picasso’s circle. Do you know if he brought the Tarot cards with him to do readings? Max Jacob, among Picasso’s closest friends, certainly did Tarot readings. Do you know anything about Max Jacob and his use of Tarot?

RF: Derain did read the cards for people he knew, as mentioned previously, and Apollinaire also talks about his arcane interests somewhere. I think that divination aside, Derain had a deeply philosophical understanding of occultism, and reading the cards was but one facet of this interest. Max Jacob has been studied in greater depth, and now there is Rosanna Warren’s new biography, which looks very promising. Jacob was mostly interested in astrology, and palmistry too, although I don’t think he wrote anything about the Tarot. He did write on astrology, not just poetry reflecting astrological symbolism, but also more involved efforts such as his Petite Astrologie or his contributions to the astrological treatises by Conrad Moricand, another member of that milieu. While the Surrealists’ use of so-called occult symbolism is now well-researched, the works of the previous generation of writers and artists would also be worth examining from this perspective as well.

BGN: Would you be willing to share your translation of Salmon’s Tarot poems and offer some insight into their meaning? Are they similar to the poems that come from 16th century Italy?

RF: Without being able to research the matter in greater depth, it is difficult to say whether these are poèmes à clef, or if they are simply using the court cards as a framework. Yet the poem entitled “Encounters” is quite revealing, since the very title reflects a cartomantic concern – the combined meaning produced by two cards drawn in conjunction. This view is further justified when we look at the text: It reads as a pastiche of the sort of sentences found in manuals of cartomancy, and in fact, most of the sentences contain keywords taken from the cartomantic tradition which ultimately originates with Etteilla in the late 18th century.

Grand Etteilla, late 19th century, courtesy of the BNF.

To my mind, the unanswered question here would be to know whether Salmon prefigured the formal experiments of the Oulipo group (Raymond Queneau, Italo Calvino, Georges Perec, Jacques Roubaud etc.) by drawing cards and attempting to write a poem around the combinations of meanings, or whether he simply picked and chose some of the keywords from a cartomantic manual. I think it would further our understanding of the creative relation between games, symbols, and the structure of literature.

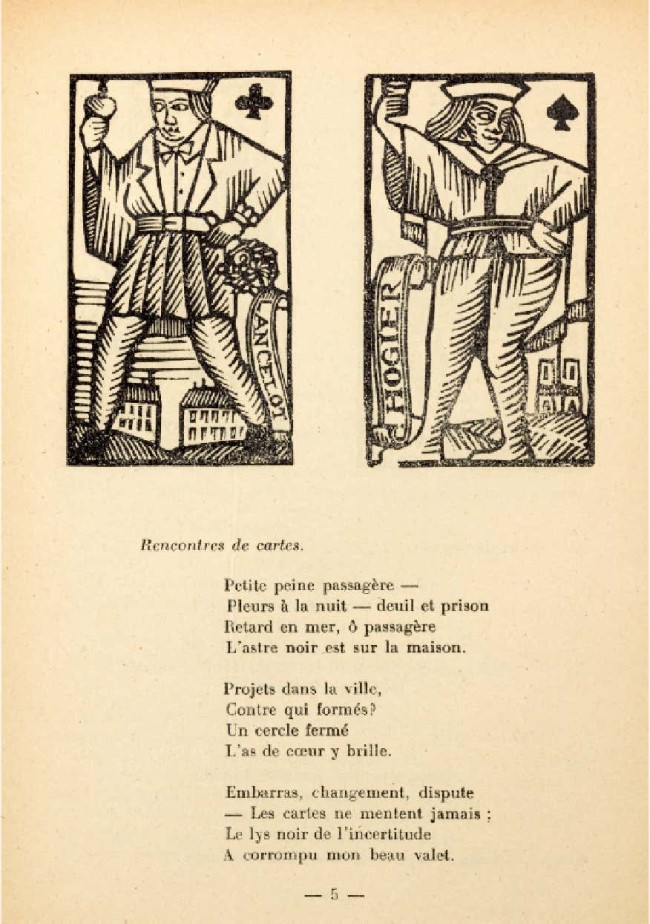

André Salmon, “Rencontre des cartes,” Cartomancie, published in Action, January 1, 1921. Illustrations : Apa (Felíu Elías Bracons)

Encounters

Trifling temporary troubles —

Tears in the night — bereavement and prison

Delays at sea, O passenger

The dark star is above the house.

Plots in the town,

Formed against whom?

A closed circle

Wherein the Ace of Hearts shines.

Bothers, changes, disputes

— The cards never lie;

The black lily of uncertainty

Has corrupted my handsome valet.

BGN: Wow, Ronan! You really nailed this translation. A tough nut to crack, too. I tried to translate it while we compared other versions of Salmon’s “Cartomancie.” You successfully captured its essence and kept the meter. A difficult combination.

The figures featured above these verses are Lancelot (lover of King Arthur’s wife Guinevere) and Hogier (Ogier, the Dane, one of the Twelve Legendary Knights of Charlemagne). A Valet in Tarot became the Jack in playing cards.

Speaking of playing cards, have you ever visited the Musée Français de la Carte à Jouer in Issy-les-Moulineux?

RF: No, unfortunately, not yet. Both times I attempted to visit when I was in the area, the museum was closed. Of course, I hadn’t thought to check the opening hours! That said, the museum has a wonderful website and has been hosting online events and exhibitions recently. In fact, they will hold a major Tarot exhibition and conference from mid-December this year till March next year, which will be well worth visiting.

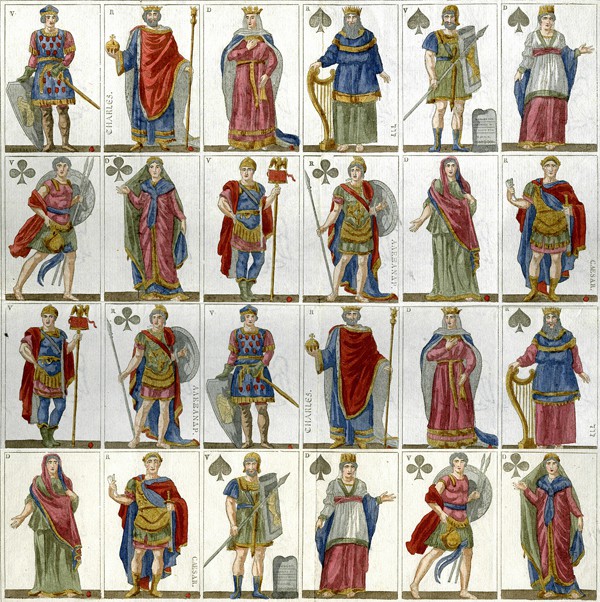

Jacques-Louis David, Imperial Playing Cards, c. 1810, napoleon.org website

BGN: It’s not far from central Paris. Issy-les-Moulineux can be reached by RATP Metro 12 at the end of the line. On the museum’s website we can find videos about their collection, including a deck of playing cards commissioned by Emperor Napoleon I from his favorite artist and celebrated Neoclassical painter Jacques-Louis David. David’s student (a woman artist by the way!), Angelique Mongez (1775-1855), completed the deck that her teacher began with the drawings of the four sovereigns Alexander, David, Charles and Caesar, each resembling Napoleon himself. Jean-Bertrand Andrieu (1761-1822) engraved the images, and famous typographer Firmin Didot (1764-1836) produced the templates to print the cards. The museum explains on the video that this Imperial deck, introduced into circulation on October 1, 1810, did not achieve great popular success.

Nicolas-Marie Gatteaux, c. 1816, found on The World of Playing Cards website

Another set of playing cards designed by Nicolas-Marie Gatteaux (1751-1832) in 1811 caught on through 1853, and a revised design produced in 1813 remains in use today. These cards and the Marseille deck probably inspired the artist Apa (Felíu Elías Bracons) who illustrated Salmon’s poems.

Thank you so much, Ronan, for your generous and highly informative responses to my questions. Are you going to publish your history of Tarot cards within the near future?

RF: You are very welcome. Right now, I have a number of books in various stages of completion. First off, I have an edition of Eudes Picard’s seminal Tarot manual ready to be published, another classic of the Tarot literature, and an anthology of late 19th century-early 20th century material, all of which I intend to publish myself. Then, I have a translation of Artaud’s New Revelations of Being in the works, and finally, I have been making notes towards a sort of literary history of the Tarot, which I suppose has been my main focus these past few years. That will take some time yet as I keep discovering new material. In the meantime, readers can subscribe to my blog to receive news of updates and publications, and I am open to offers from enterprising publishers as well!

BGN: Best wishes to you, Ronan, for all these exciting projects and endeavors. I look forward to seeing your Tarot studies in book form. In the meantime, your blog is a feast for the eyes and mind.

For Further Reading and Discovery

Ronan Farrell’s Blog: Traditional Tarot: Desultory Notes on the Tarot https://traditionaltarot.wordpress.com/

Ronan’s post on André Salmon’s Cartomancy: https://traditionaltarot.wordpress.com/2021/01/15/andre-salmon-cartomancy-excerpts/

Le Musée Française de la carte à jouer: https://www.museecarteajouer.com/

Lead photo credit : B.P. Grimaud, Ancient Tarot de Marseille, c. 1930

More in Art, gallery, history, images, Tarot

REPLY

REPLY