Camille Pissarro and the Battle for Impressionism

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

It is sometimes difficult to imagine the often extreme poverty that many of the Impressionists endured during their life times — considering their paintings now sell for vast sums of money. Only a few had private incomes or family wealth; Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas and Berthe Morisot were exceptions, immune to the hardships (although not the criticisms) that other Impressionists had to face on a daily basis.

Camille Pissarro suffered doubly. His family had money, but disapproved of his choice to be an artist (Pissarro would have described it as a compulsion), and although there was never any doubt that he was well loved, on the death of his father, he was disinherited, his mother promising only to cover his meager rent. But the family had another insurmountable objection long before that.

And that was Pissarro’s choice of mistress and the mother of his children.

Camille Pissarro and his wife, Julie Vellay, 1877, Pontoise. Unknown author

By 1857, he was sharing a studio at 56, Rue Lamartine with a gentle mannered Danish painter, David Jacobsen. The rest of the Pissarro family were living in Passy on the outskirts of Paris. Pissarro visited his family often and very soon became infatuated with their newly employed maid, Julie Vellay. She was a typical bonne. Employed through an agency, these women were usually untrained, unsophisticated country girls, innocent to the sometimes laxer morals of city life.

Hailing from Grancy in Burgundy, Vellay was slim and graceful with the high complexion of a girl used to the outdoors. Pissarro was soon entranced by her. They met in secret on her days off and within a year, the inevitable happened and Julie was pregnant. This was not a typical artist/model affair. Pissarro truly loved Julie, but his mother was much more than scandalized, she was utterly ashamed that Camille could even contemplate a liaison with a bonne, let alone acknowledge a child by her. From that moment on, neither Julie, nor the children they produced over Pissarro’s lifetime, existed in his mother’s eyes.

There was no question of marriage until his parents had died – even then, they married quietly in London.

But Pissarro had proved to be unpredictable, long before he met his wife.

Two Women Chatting by the Sea, St. Thomas, Camille Pissarro, 1856

Jacob Abraham Camille Pissarro was born on the island of Saint Thomas (now the U.S. Virgin Islands) on July 10th, 1830. The Pissarro family had already been touched with a certain notoriety. His father, Frédéric Abraham Gabriel Pissarro, was of Portuguese Jewish descent and his mother, Rachel Manzano-Pomié, was from a French Jewish family. Their marriage in the small Jewish community of Saint Thomas had caused quite a stir. Pissarro’s father had taken over the hardware store of his deceased uncle, Isaac Petit, whose widow, Rachel, Pissarro’s father subsequently married. In Jewish law a man is strictly forbidden from marrying his aunt. Camille Pissarro and his three siblings were consequently educated in the all Black primary school.

At the age of 12, Pissarro was sent to boarding school in Passy, near Paris. He stayed there for five years; apart from his formal education at the Savary Academy, he was also tutored in drawing and painting. He immersed himself in Parisian art galleries, which irrevocably set the course for his life.

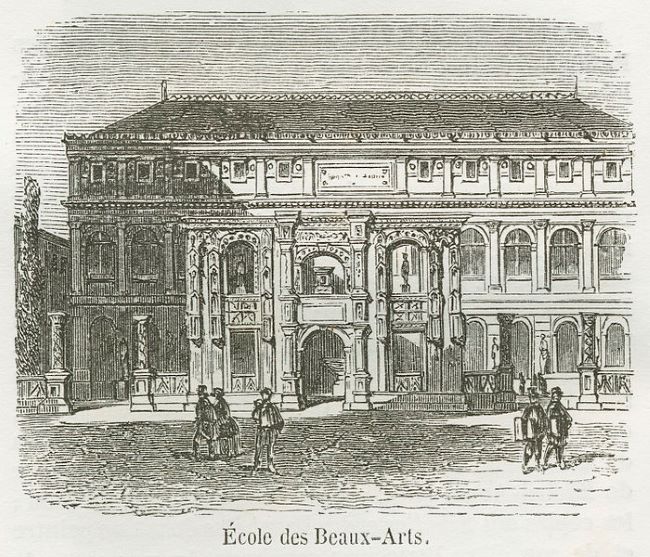

Back on Saint Thomas, Pissarro’s father had other ideas. Obliged to work in the family business as a port clerk, Pissarro’s artistic ambitions were not dimmed, and he spent every spare hour drawing and painting scenes of Saint Thomas. A chance meeting with a Danish painter Fritz Melbye persuaded Pissarro to abandon his family and job and accompany Melbye to Venezuela where he stayed for two years drawing, sketching and painting everything and anything he possibly could. After two years he returned to Paris to work for Melby’s brother, Fritz. Pissarro enrolled swiftly in the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, studying under Corot.

Ecole des Beaux-Arts

It was in Paris that Pissarro was introduced to what became the Bête Noir of of the emerging Impressionist artists: the Paris Salon. Acceptance in the Salon’s annual exhibition was the ultimate Catch 22. At the time, the Salon’s annual exhibition was essentially the only way that young, unestablished artists could gain exposure and recognition both in the art world and with the general public. The catch was that the official body of the Salon still only recognized traditional works of art. At first Pissarro followed this edict, and in 1859, his first painting, Landscape at Montmorency, was accepted by the Salon. The Salon, of course, had absolute discretion on how and where paintings were hung. Even if one was perhaps grudgingly accepted, it could be hung so high, that it could only be viewed with difficulty by the general public. (Manet had submitted his poignant L’Absinthe to the same exhibition. It had been roundly rejected.)

But painting in the accepted academic Salon style was fundamentally an anathema to Pissarro, and encouraged by Corot, and influenced by Courbet, Pissarro began painting in “plein air.” Painting rural scenes of nature outdoors became a passion that endured all of Pissarro’s life.

Camille Pissarro, Paysage à Montmorency, Vers 1859. © Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

There were three things that — combined together — contributed to this new mode of “plein air” painting.

The first was the advent of the trains. In 1842, enough tracks had been laid to bring both the country and the coast within easy reach of Paris. Then, the seemingly simple invention of a collapsible, light-weight easel was a revelatory game changer for artists who previously had been encumbered with heavy, unwieldy easels, impossible to carry long distances. The third new invention changed everything. Paint in tubes. No more mixing of paint in pig’s bladders; instead lightweight, ready mixed tubes of paint fit into a compartment in their portable easel. There was a fourth invention, much beloved by Pissarro: flat paint brushes, known as “feral.” Paint brushes previously had been round, made from sable, but these flat, blunt ended paint brushes, made with hog’s hair, proved perfect for the broad brush strokes of the burgeoning Impressionist artists. There was also an unspoken uniform: blue, workman smocks – blue so as not to reflect on water – and big hats which were worn more to protect the paint than their heads. And suddenly, a whole new era of painters and art was born with Pissarro at the forefront.

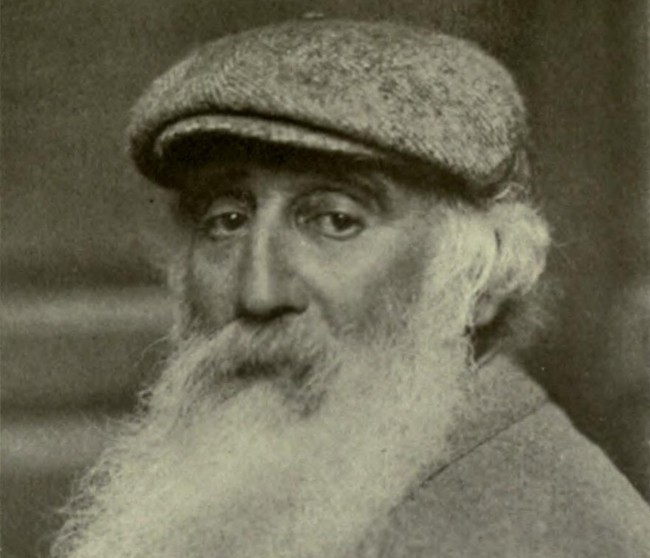

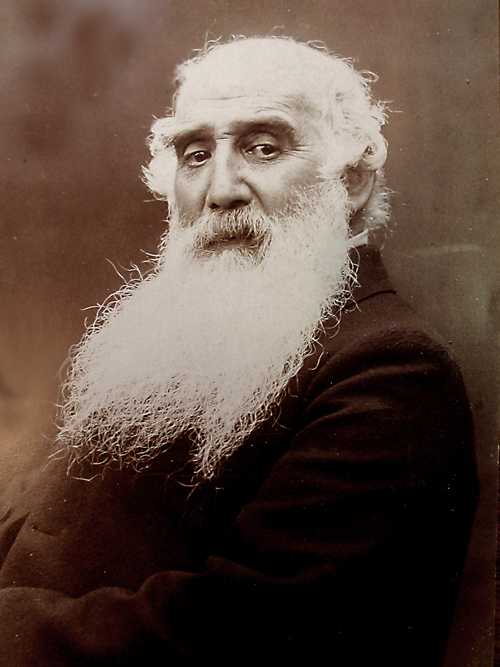

Portrait of Camille Pissarro. Unknown author. Publ. Art Gallery of New South Wales (2006)

Claude Monet, Armand Guillaumin and Paul Cézanne — attending the free school, the Academie Suisse, along with Pissarro — were like-minded in their dissatisfaction of the dictates of the Salon, all desiring to paint in a more realistic style. It was to prove a long and torturous road for many of them.

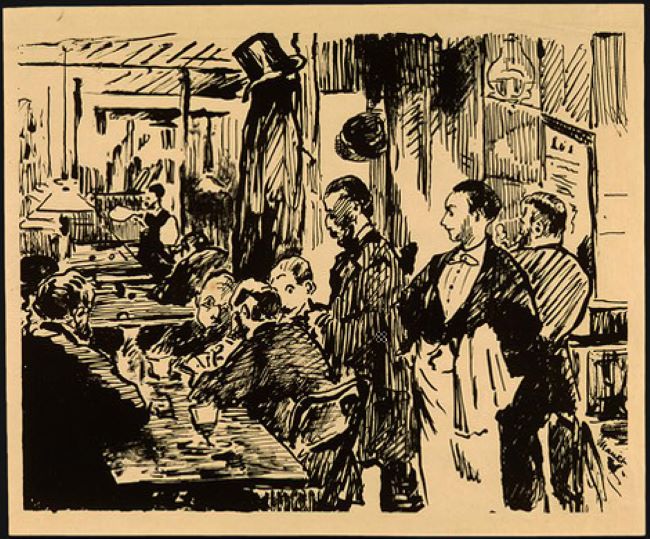

As the salon rejected this new style of painting, so their little circle of innovative artists expanded, James Whistler and Henri Fantin-Latour among them, railing against the Salon in the Café Guerbois every week. There was a renewed optimism, however, even among the most discouraged of them, for the upcoming 1863 exhibition. Each artist believed that they had honed their metier, improved their craft, now worthy of acceptance by the Salon. Only their poet-friend Baudelaire had misgivings. He had been passed, illicitly, the list of the jurors. The same old names, “the arch preservers of the past,” he’d warned.

Au Café, by Édouard Manet, depicting the Café Guerbois. National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

Pissarro still traveled out to Auvers-sur-Oise, painting all day before returning to pregnant Julie in their studio in the Rue Neuve-Bréda. His output was prodigious and he had finally chosen three medium-sized village paintings for the exhibition.

In the last week of April 1863, some 3,000 aspirants converged on the Palais de L’Industrie with their paintings — some hoisting them on their backs, others accompanied their canvases in carriages, on carts, or simply carried them, like Pissarro, on foot.

Manet had submitted his Luncheon on the Grass, doubtless wondering if it would scandalize or be appreciated for the groundbreaking work it was. All paintings had to be gold framed to be accepted by the Salon, an expense few of them found easy to afford but had no choice if they wanted their paintings in the exhibition. The artists waited five days for the results.

The entire group was rejected.

This time the indignation and anger was palpable. For the first time, thousands of the rejected paintings were left in the store house where offended painters had refused to take them back. Manet’s father, a magistrate, had agreed to write to the Emperor; Baudelaire promised to put his name to an article denouncing the choices of the Salon, others had friends in high places… Delacroix, terminally ill, put his name to the voices and avant-garde collectors joined in the uproar, claiming that Paris was “no longer the art capital of the world.”

Édouard Manet, Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (1863), Paris, musée d’Orsay.

Napoleon III, already an unpopular ruler, was unwilling to suffer more unwanted criticism and bad publicity over a group of protesting artists and ordered that the rejected canvases left at the Salon be exhibited for his personal perusal. His grand throne chair was transported from the palace and he then asserted that he was unable to tell the difference between those paintings accepted by the Salon and those refused. He ordered the politician, the Comte de Nieuwerkerke, to come up with a solution to display the paintings that the Salon had rejected. An empty building across from the Palais de L’Industrie was chosen. It was to be called the Salon des Refusés (“the exhibition of rejects”).

When the Emperor and the Empress announced that they would be attending the opening of the Salon des Refusés, it seemed that success was assured, and the public would turn up in droves, even though Pissarro and his group were well aware that some of the paintings being shown were execrable.

But the Comte de Nieuwerkerke, an advocate of the accepted Salon paintings, along with the hanging committee, would have their revenge. The most ludicrous and badly painted canvases were hung in the most prominent positions in the first gallery.

Portrait of Napoléon III by Jean Hippolyte Flandrin. 1862. Public domain

Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass was hung side by side with Whistler’s Lady in White. Whistler’s painting was viewed with incomprehension, and Luncheon on the Grass was vilified, viewed with outrage and accusations of immorality. The exhibition was mocked, laughed at, insulted and overwhelmingly rejected. The Impressionists had suffered an almost deadly defeat.

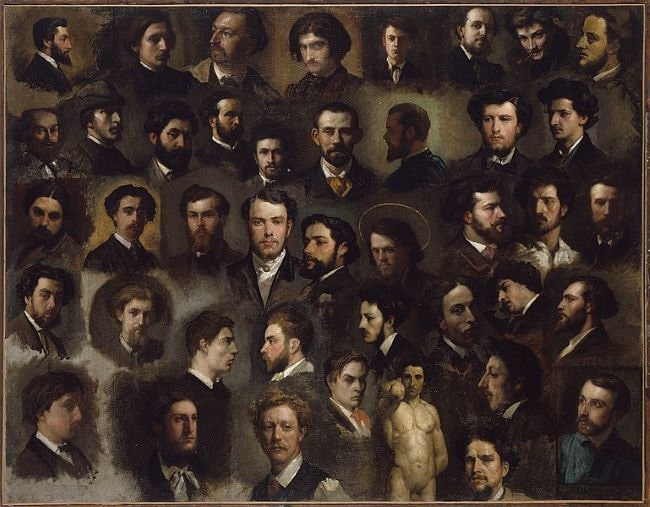

43 portraits of painters of l’atelier Gleyre. Anonymous. Between 1856 and 1868. Petit Palais, musée des Beaux-arts de la Ville de Paris

Pissarro gave up his studio and moved to La Varenne, 15 miles southwest of Paris, more than an hour away by train. His mother accused him of living like a peasant, but here Julie, as a country girl, came into her own. She bought chickens and rabbits and planted vegetables in their little garden. Julie was, throughout Pissarro’s life, adept at living frugally, living off the land, making ends meet and often simply doing without, so that Pissarro could continue to paint. And Pissarro certainly did that. He painted relentlessly, from first light until the fading of the day. Their little house reeked of turpentine but the canvases were stacking up. He still traveled to Paris often, to see his parents and to catch up with his friends and their news. It was in their favorite bar that he was introduced to Auguste Renoir who was sharing a studio with Frédéric Bazille on the Rue des Beaux-Arts. Renoir, still only 22 and from a poor family, had started earning his living at age 13, painting porcelain and then blinds. Like Pissarro, Renoir lived frugally. He had made good money and determined to use his savings to register at the Atelier Gleyre for two years. Pissarro was enchanted by the youthful Renoir’s enthusiasm. Another like-minded artist to join the group.

Portrait of Paul Cézanne, by Camille Pissarro, 1874. National Gallery

The following year, the Salon accepted two of Pissarro’s oils, a study near La Varenne and a painting of La Roche-Guyon. The jury, having been admonished by Napoleon III, bent over backwards to include more naturist works. Manet, Renoir, and Fantin-Latour were also accepted, but a furious Cezanne was once more rejected.

A week later, Pissarro was approached by Alfred Cadart, a Parisian art dealer from Chez Cadart et Luquet, to place his two paintings from the Salon exhibition in the window of his gallery in the Rue de Richelieu. Pissarro was ecstatic. As was Julie – another child was on the way.

Pissarro’s relief was short lived. Even with a selling price of about $5, which would not even cover the cost of the canvas and the paint, there had been no interested buyers, and Cadart returned the paintings to Pissarro with apologies.

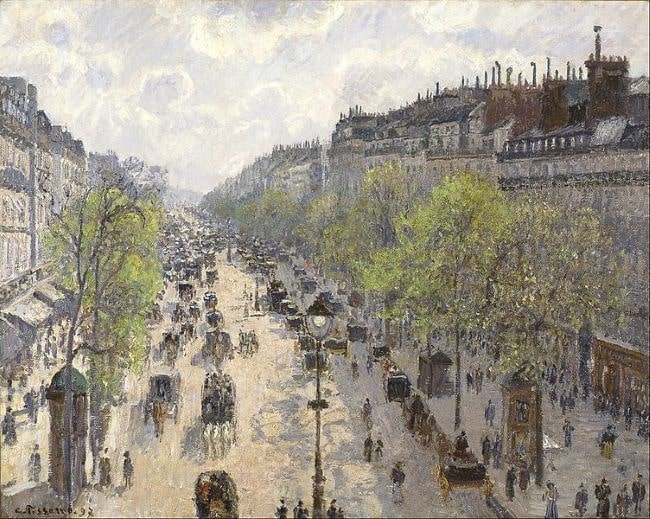

Camille Pissarro, Boulevard Montmartre, Spring. 1897. Public domain

Another much greater blow was to befall Pissarro in January 1865. His father had been ailing for months and despite doctors and medication and even Dr Gachet’s homeopathic remedies, he died. He had always been more understanding of Pissarro’s life choice, less censorious about Julie and his illegitimate grandchildren than Pissarro’s mother who remained obdurate in never acknowledging their existence. Pissarro was devastated at the death of his father, but nevertheless assumed that he would benefit from his will, enough at least to secure his future for a few years. He had in fact been disinherited. Half the estate had gone to his mother, the other half to his brother Alfred. Camille had been left absolutely nothing.

He was 35 years old, with a family and wife to provide for, and no-one was buying his paintings. His mother would pay only half his rent now but continued with his small allowance.

Édouard Manet, Olympia, 1863.

Once more Pissarro submitted two paintings to the Salon’s exhibition the following year. To his delight they were both accepted, but Manet was even more euphoric. His painting Olympia, depicting a naked prostitute on her bed with her Black maid presenting her flowers from an admirer, had also been accepted. It was found to be so shocking, so obscene by the public that it is was spat on; someone tried to slash it with a knife and the crowds, outraged and revolted by the subject of the painting, still pushed each other for a better view and ignored the other works. Manet invited Pissarro to his studio in the Rue Guyot. Manet’s luxurious studio was a far cry from anything Pissarro could ever hope to afford. He was introduced to Berthe Morisot, but came away unsettled by the disparity of their living arrangements.

Pissarro found a cheaper house on the outskirts of Pontoise. The house was big, but stark, isolated along a dirt track, and once more Julie began the task of making a garden. But she was lonely; the neighbors distrusted strangers, and she was still an unmarried mother. For Camille, however, it was perfect, the adjoining fields, new pastures for him to paint. And Pissarro still had his trips to Paris, where the loyal, vociferous, fluid group in the Café Guerbois now included Degas.

Jalais Hill, Pontoise, by Camille Pissarro, 1867. Metropolitan Museum of Art

But money was a never-ending problem. They were living on the kindness of others. His brother Alfred always offered to pay for the gold frames needed for the Salon, his sister Emma sent clothes and gifts of food for the children and the eccentric Dr. Gachet accepted paintings in lieu of payment, but every spare sou went toward canvases and paint. Julie, mostly uncomplaining, ensured that the family didn’t starve.

In 1867, another Exposition Universal was announced. Bigger than ever, more paintings would be required to fill the space. Optimism among the Impressionists spilled over once more. Pissarro had been impelled to visit the pawn broker with his father’s gold watch and one of Julie’s copper pans just to feed the children, so the prospect of acceptance and a sale had lifted both his and Julie’s spirits – only to be dashed yet again. The jury decided that this year they would be ultra cautious and select even fewer paintings. It was the last straw. Courbet, who had leased a plot next to the Salon exhibition and built his own gallery, offered it to the group. Despite all of them contributing whatever they could, it was not enough, and now neglected, Courbet’s pavilion, its roof falling in was deemed a dangerous nuisance by the City of Paris and demolished along side the hopes of the group.

Camille Pissarro. Scène villageoise, between 1854 and 1855

But nothing deterred Pissarro. Neither poverty, nor rejection repressed him. He painted like never before in the fields around Pontoise, and along the banks of the Seine at Bougival. He painted like a man possessed. And this time two of his paintings were accepted by the Salon, and despite the fact that they were hung near the ceiling, both Emile Zola and Odilon Redon wrote glowing reviews. But still they didn’t sell.

In 1869, the Salon accepted only one of Pissarro’s paintings. Once more it was hung at the highest level, but despite the insult, Pissarro acquired his first collector, Jean-Baptiste Faure, a popular singer at the Paris Opera. Pissarro’s change of fortune was on a roll. After Faure came Gustave Arosa, a banker, then a certain monsieur Lecreux from Lille bought two more of his paintings, Coconut Palms by the Sea and Two Women Conversing by the Seashore. Pissarro was now in the incredible position to help out Monet and Renoir, both struggling to feed themselves.

Pissarro’s Pear Trees and Flowers at Eragny, Morning, WikiArt Public Domain

The Franco-Prussian war was to make Julie an honest woman. Escaping from the bombardment of Paris in 1870, the Pissarro family made their way to London, and finally Julie and Camille were married. It was here, too, that Pissarro was introduced to the art dealer Durand-Ruel, who was to become a good and trusted friend, while helping change Pissarro’s fortunes back in Paris. But perhaps even more importantly, Pissarro was back with his contemporaries, Monet, Renoir, Sisley and the others.

The bad news was that when Pissarro reclaimed his house in Louveciennes, the Prussians who had occupied it had destroyed hundreds of his watercolors and drawings, using them as mats to wipe their feet on. Pissarro had to take consolation that not all of his paintings had been trashed. He had hidden some and those he’d stored for Monet were still salvageable.

And it was Monet, tired as so many of their group were of the intransigence of the Salon, who suggested that they attempt their own exhibition – an exhibition of Batignolles Independents.

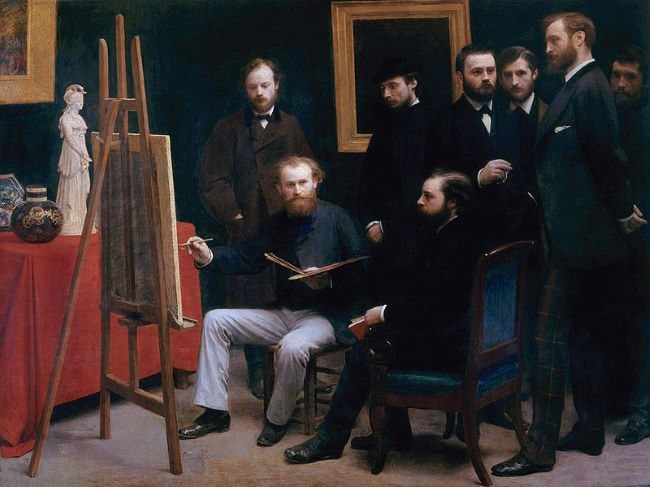

Henri Fantin-Latour, A Studio at Les Batignolles, 1870

There was a nucleus of nine: Monet, Renoir, Sisley, Bazille, Pissarro, Cezanne, Morisot, Manet and Degas. Others included Braquemonde, Guillaumin, Guillemet, Fantin-Latour, Caillebotte, Gauguin and the American artist, Mary Cassatt and Nadar who hosted the first exhibition in his studio at No. 35 Boulevard des Cappucines. The exhibition lasted a month from April 15th to May 15th, 1874. Once again, the public did not respond well to this new style of painting. The artists were laughed at and derided. A second exhibition the following year provoked violence by the crowd, any paintings sold were sold at the lowest price possible, leaving many of the artists in need of loans to simply survive. The third exhibition did not fare any better and in desperation the 45 paintings not withdrawn after the exhibition went up for auction at the Hotel Drouat.

It was yet another disaster.

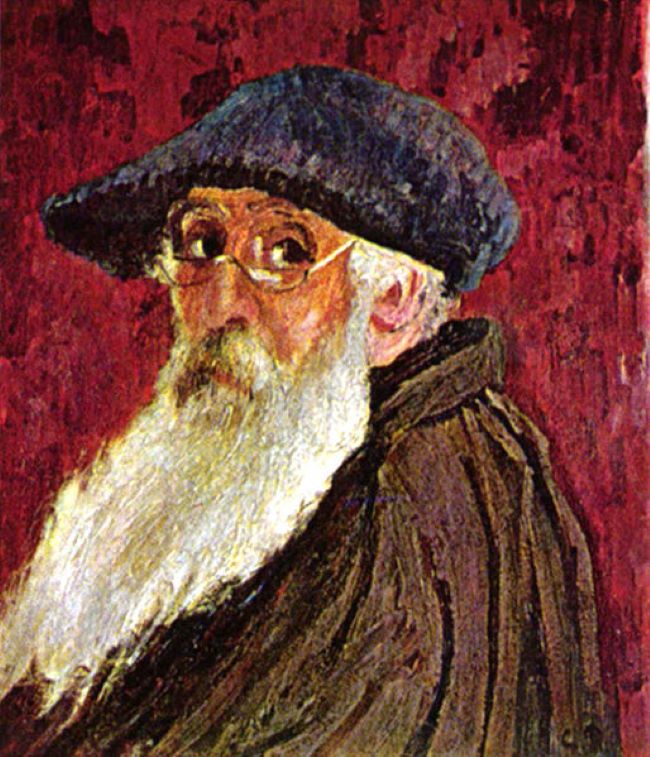

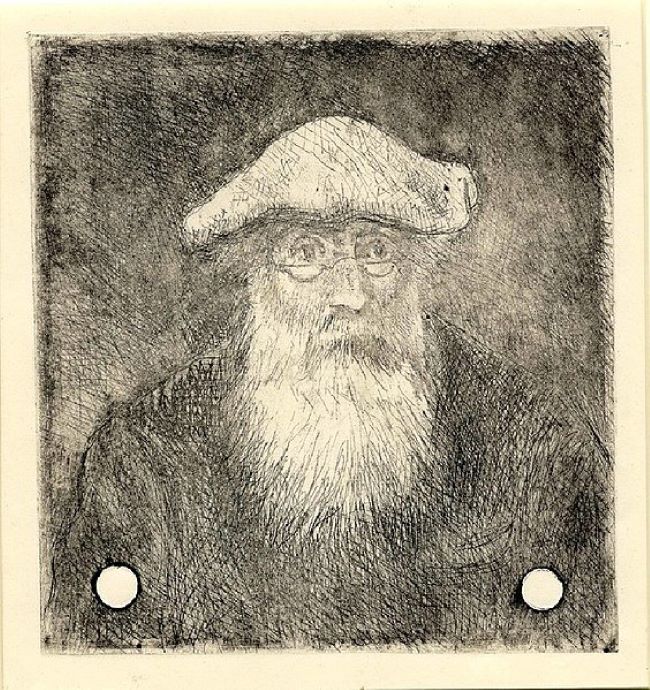

Camille Pissarro, Self portrait, 1898

But Gustave Caillebotte was obstinate in his determination for a fourth exhibition. Many of the original artists no longer had the heart or masochistic tendencies for another public humiliation. Monet, Degas and Pissarro were joined by Cassatt and Caillebotte who had found and leased premises at 28, Avenue de l’Opera. Others were invited, Bracquemonde, Cals, Lebourg and Rouart. While this fourth exhibition was not an overwhelming financial success, nor was it so overwhelmingly vilified. The artists took courage from that but, courage did not help to pay their bills and Pissarro found it impossible to rally them for a fifth exhibition. A proposed sixth, despite Pissarro pleading with Monet, Renoir and Sisley, seemed destined to go the same way, but Degas, Morisot, Guillaumin and Rouart agreed and Gauguin promised to send his oil paintings from Pontoise. Pissarro, with his 28 paintings, overwhelmed the exhibition. It was mildly successful, but not enough to be life-changing. Only the art dealer, Durand-Ruel was keeping the wolf from the door.

Camille Pissarro, Avenue de L’Opera (Effect of Snow in the Morning), 1898. Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts

The years passed. Pissarro’s admiration for Pointillism and his friendship with Seurat had caused rifts in his old friendships from the Cafe Guerbois. Only his family— six sons, a daughter, and Julie — sustained him. (All his sons became painters and five generations of Pissarros followed in his footsteps.) When his mother Rachel, died at the age of 94, she left everything to his brother Alfred and his family. Once more, Camille had been disinherited. His mother had not forgiven him, even on her death bed for marrying Julie Vellay, her bonne.

In 1890, Pissarro was 60 years old and despite the help of Paul Durand-Ruel and Theo Van Gogh doing their best to sell his paintings, he was still struggling to feed his family and deeply dismayed by Vincent Van Gogh’s shocking death. His eyesight was deteriorating and the injections of silver nitrate into his eye ducts were both painful and expensive.

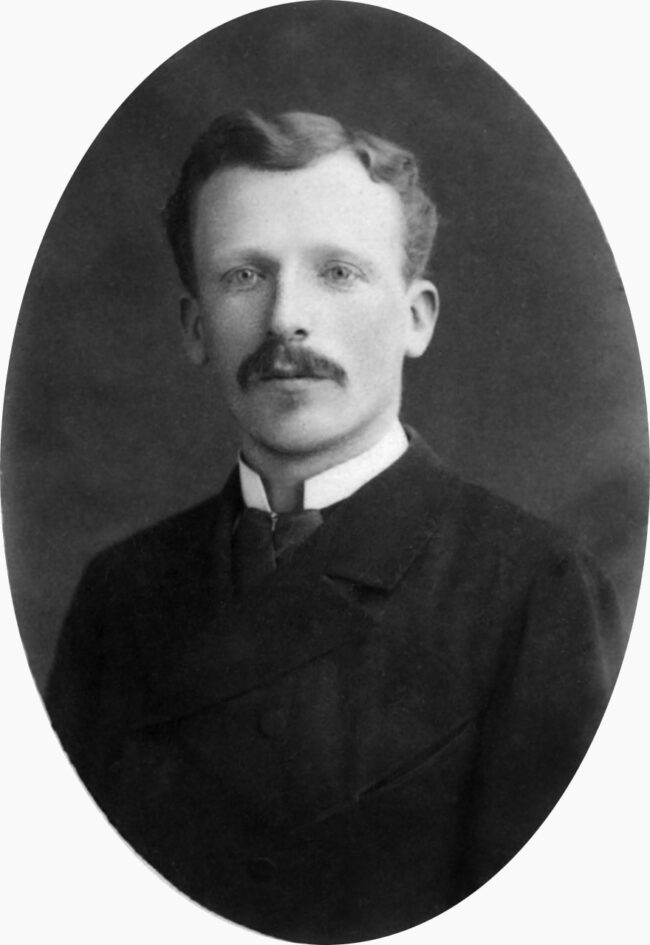

Theo van Gogh in 1888. Public domain

But still Pissarro painted, and in 1892, Durand-Ruel came through on his promise to hold a one man exhibition for Pissarro. Seventy-one of Pissarro’s paintings from the 70s, 80s and 90s graced Durand-Ruel’s gallery. The exhibition was a success. It had brought Pissarro some welcome publicity, some laudatory comments but not vast riches. He had gone to London to sort out problems with his son Lucien’s forthcoming marriage when he received a letter from Julie. On hearing that their rented house was going up for auction, Julie had taken the first train to Giverny and borrowed money from Monet (now comfortably off after his marriage to Madame Hoschede and the sale of his paintings). It was to be Julie and Camille’s first house that they had owned, and Pissarro, despite the worry of how he would repay the loan, was as delighted by the purchase as Julie.

Camille Pissarro self-portrait

Pissarro’s paintings began to sell. He completed a series of paintings of Paris boulevards but returned to his house in Eragny to complete his next contribution to Durand-Ruel’s upcoming exhibition. His paintings all sold.

In 1901, Pissarro sold a painting for 10,000 francs and two years later the Louvre bought two of his paintings. After more than 40 years, Pissarro had proved he had overcome every rejection of the Salon and his critics.

He died on November 13th, 1903 and was buried alongside his parents in Père-Lachaise Cemetery.

Lead photo credit : Camille Pissarro, c. 1900. Unidentified photographer

More in Bête Noir, Café Guerbois, Camille Pissaro, Ecole des Beaux-Arts, Julie Vellay