Remembering Theo Van Gogh

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 80 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Theo van Gogh is best known for being the brother of artist Vincent van Gogh and for the patience and financial backing he offered him. Theo himself made an important contribution to the French art world by introducing Impressionist stars such as Monet and Degas to the public. He persuaded his employers Goupil & Cie to exhibit their works and and later branched out on his own to specialize in them. Without Theo, and the life’s work of his young widow Johanna Bonger, Vincent van Gogh wouldn’t be one of the world’s most recognizable painters. Like his older brother, Theo had a short, poignant life and tragic death.

The Van Gogh family had been in the business of selling paintings throughout the 1800s. Theo’s uncles Hendrick and Cor were book and art sellers. Uncle Cent van Gogh was a partner in the very successful art dealership Goupil & Cie with branches in major European centers. Just months after his 16th birthday, Vincent van Gogh became a junior apprentice at his uncle’s business in The Hague, moving to the London location in 1873, and from 1875-76 at the Paris head office.

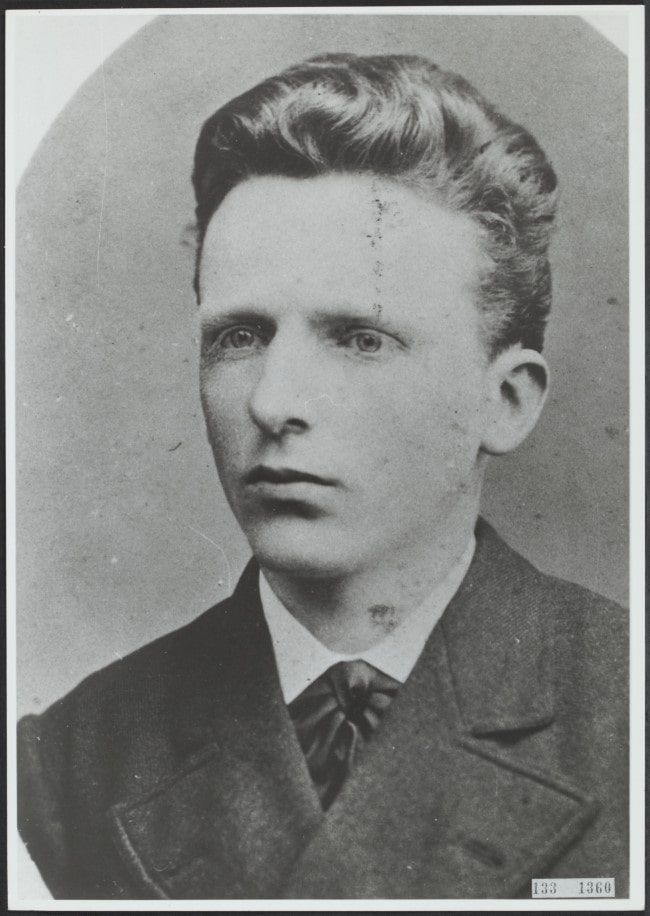

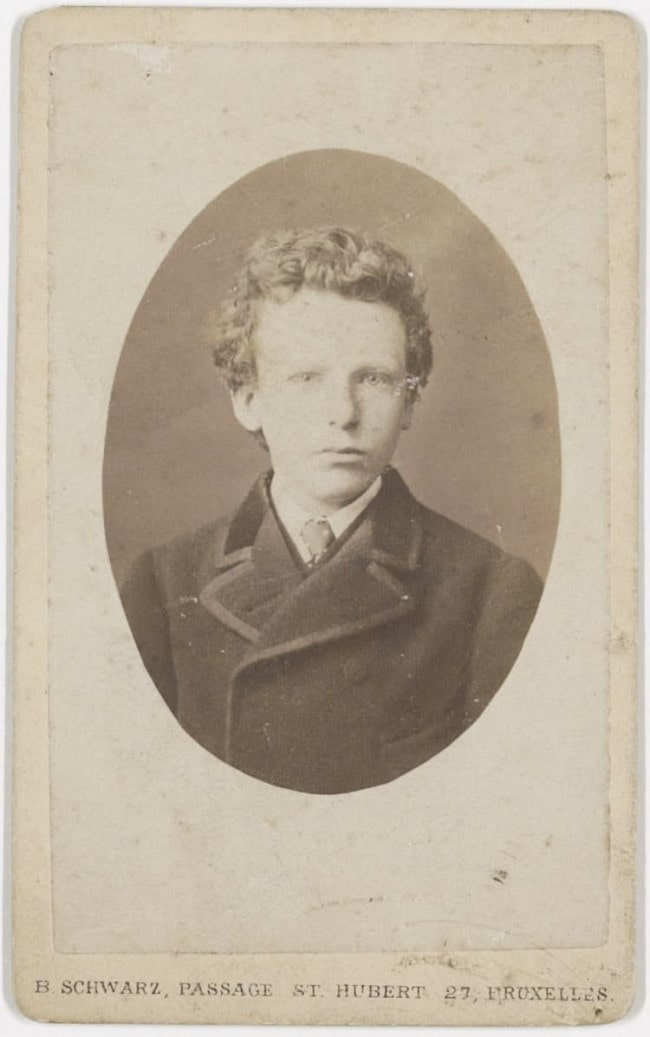

Theodorus van Gogh, born May 1, 1857, four years after his older brother, was a thinner, paler, more precise version of Vincent. Theo would follow the requisite path and work for his Uncle Cent. At 15, Theo took a position at Goupil’s office in Brussels. He was a frail child, away from home for the first time, and he endeavored to make his parents proud. Theo did well at the Brussels branch. Modest and intelligent, his employers entrusted him with some managerial duties. He manned the Goupil & Cie kiosk during the 1878 Exposition Universelle. At first, Theo found Paris chaotic and confusing but he returned permanently to Goupil’s Paris headquarters in late 1879.

Theo van Gogh age 15, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

Following Cent’s retirement, the firm became Boussod & Valadon and Theo became manager of their office on Boulevard Montmartre. When he let an apartment at 25 rue Laval (now Victor-Masse), he was smack in the epicenter of the modern art world. Theo was au courant with not just art, but also theater, music, food, and fashion.

Theo was a highly competent expert at Boussod & Valadon. His success as a dealer of contemporary art was a stark contrast with the path of his older brother. Vincent failed at his attempts to be an art dealer, language teacher, bookseller, and lay preacher. Theo advised Vincent to develop his skill as an artist and to stop making life so difficult for their parents. Vincent followed this brotherly advice and decided art was his life’s calling. Theo was the steadier of the two and became Vincent’s anchor. Theo selflessly started providing his ne’er-do-well brother with painting supplies and monthly support.

Vincent van Gogh’s view from Theo’s apartment by Google Art Project

Theo was part of his company’s progression towards Impressionism, surreptitiously introducing Sisley, Pissarro, Monet and Renoir into the gallery. Yet his bosses showed little interest in the the value of the new and still less-than-popular Impressionistic style. Theo was tempted to walk out the door and start business for himself but when Theo entreated his artistically-inclined uncles for funds to finance a gallery of his own, they refused him.

Frustrated at work, Theo wanted to withdraw from society. Theo and Vincent both suffered from melancholy and when their father died of a sudden stroke in 1885 the pair were despondent. So when Theo invited Vincent to join him in Paris he jumped at the chance. The duo shared Theo’s small apartment throughout the spring of 1886, moving on to a larger flat at 54 rue Lepic. But Theo had no respite from his daily stresses – when returned home in the evening he had to deal with the volatile Vincent.

Theo’s apartment building at 54 rue Lepic © Hazel Smith

Theo personally introduced Vincent not only to the paintings of the Impressionists, but also to the artists themselves – Gauguin, Cezanne, Toulouse-Lautrec and Seurat. Theo included Vincent with this group of up-and-comers, but struggled to sell his brother’s work.

Theo van Gogh was a significant threat to competing Paris art dealers. When he bought 14 works from Monet in 1887, it was a major attack on rival dealer Durand-Ruel’s core group of artists. There was talk of sending Theo to Great Britain or America to counteract Durand-Ruel’s successes abroad. As the question of money for the two brothers – artist and patron – seemed to be without answer, Theo thought seriously about this.

Theo had now assumed the role of the wise, older brother. Vincent sat up at night next to his brother, yammering about the future, while his brother tried to sleep. Theo’s affection for his brother was sorely tried. He wrote to his sister Wilhelmina.

“There was a time when I loved Vincent a lot and he was my best friend. But that is over now. It seems worse from his side. For he never loses an opportunity to show me that he despises me and I revolt him. That makes the situation at home almost unbearable. Nobody wants to come and see me because that always leads to reproaches and he is so dirty and untidy that the household looks less than attractive. All I hope is that he will go and live by himself…”

In 1888, Theo persuaded Gauguin to join Vincent in his plan to set up an artist’s community in Arles. Providing the rent and the furniture for the Yellow House, Theo now had two penniless painters to worry about. Theo had Gauguin on retainer, and of course Vincent relied on his younger brother for all his cash flow. Thinking he and his brother to be partners in art, Vincent wrote a continuous stream of letters. He felt obliged to keep Theo informed about everything he was painting in return for his financial support. Vincent and Gaugin sent Theo pictures for him to sell, but they ended in the ever-increasing pile of unsold art at rue Lepic.

Galerie Goupil headquarters, Paris, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

Theo forged ahead, promoting the new style of art. He exhibited Pissarro’s latest works. Even grumpy old Degas allowed him to set up a small exhibition of nudes in January 1888. Ironically, Theo sold an important Degas work to the doctor who would treat him in his final days. Theo launched a Monet exhibition in 1889 which proved to be very successful.

Another success was the sweet love story that developed between Theo van Gogh and Johanna Bonger. Johanna had gently rebuffed Theo’s advances when they originally met in the Netherlands – she had a different beau. But patient Theo persevered to win her, writing her more than 70 tender and innocent letters. After an idyllic encounter in Paris in late 1888, the couple decided to marry. Theo gushed to his mother: “I loved her too much and now that we have seen one another a great deal during these last few days, she has told me she loves me, too.”

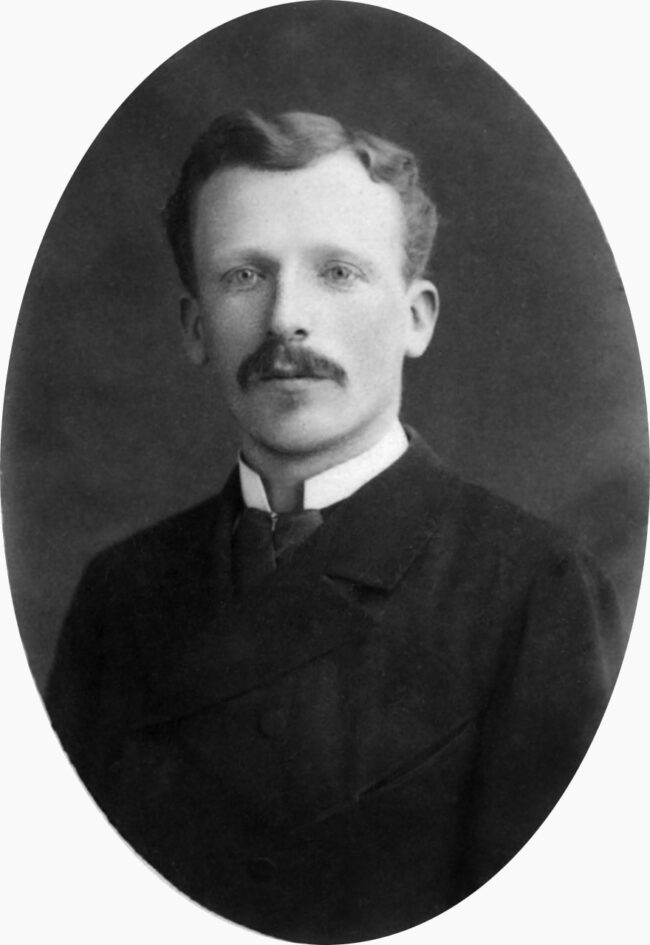

Theo van Gogh in 1888. Public domain

Preparation for their wedding began. There was the question of where they would live. Theo’s dilemma was that his rue Lepic apartment was too far from work to return home for lunch! He found them a new nest, an apartment at the bottom of Montmartre at 8 Cité Pigalle. He even sent Jo a fabric swatch of their new curtains. “What a nice, cozy home we shall have.” Johanna wrote back to her fox-haired fiancé. After a round of family visits in Amsterdam, they married on April 18, 1889. After a blissful night in Brussels they arrived in Paris where Theo escorted his bride into their new flower-strewn apartment. They delighted in the thought of the days spreading out before them as husband and wife. She’d be widowed within two years, but if it wasn’t for Jo, as she was referred to, Vincent van Gogh wouldn’t be a household name.

Less than a week after their wedding, and five months after Vincent’s ear-slicing incident, Theo received a letter from a doctor in Arles requesting Theo’s authority to commit Vincent to the local asylum. Although they had never met, Jo wrote to Vincent at St Rémy, extolling Theo’s virtues. “… I wish you could see how nice and cozy Theo had arranged everything before I came. The bedroom, in particular is so sweet, very light and lots of pink in it.” Jo added: “Every Sunday morning is spent rehanging and arranging everything. It’s so wonderful when Theo’s home for the whole day on Sundays.”

Johanna Bonger van Gogh, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

At first Jo warmly welcomed Theo’s artist friends into their home – they expanded her world. But Theo began to tire. He came home faithfully at 7:30 p.m. and fell into bed early. Jo had previously confided to Vincent that Theo didn’t look well. She worried when she became pregnant that their baby wouldn’t thrive as his parents were in feeble health. A healthy Vincent Willem was born January 1890.

Johanna Bonger van Gogh with son Vincent Willem 1890, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

Now that Theo had a family, Vincent didn’t want to return to Paris to burden them. With Vincent’s time in Arles at an end, Theo asked the artist Pissarro’s opinion about Vincent’s care. Pissarro, who lived in Pontoise, recommended Dr. Gachet – a physician/artist from a neighboring town who seemed like the ideal man to care for his brother. This enabled Vincent’s smooth transition from Arles to Auvers-sur-Oise.

In the spring of 1890, Vincent, Jo, Theo, and the baby met for a happy afternoon at Dr. Gachet’s house. However, Vincent sensed that Theo was finding it hard to play the role of his committed patron. Theo’s position within the firm started to falter. He couldn’t rid himself of a cough so terrible that even Vincent noticed. By June Theo was very ill, suffering from nervous exhaustion and finding it hard to care for his own family let alone Vincent.

Vincent, as the story goes, shot himself in the abdomen in the wheatfields above the town of Auvers-sur-Oise and died at the Auberge Ravoux on July 30, 1890. Theo was in complete despair following Vincent’s death. He was urgent to get Vincent the recognition he deserved, even approaching his rival Durand-Ruel to organize an exhibition of his brother’s works. The last meaningful act that Theo was able to undertake was an exhibition of Vincent’s canvases in his apartment in September 1890.

Vincent’s bedroom at the Auberge Ravoux © Hazel Smith

Theo didn’t die of a broken heart, but the stress of Vincent’s death may have caused Theo’s illness to accelerate rapidly. Theo lost his sanity just three months after his brother died. The common diagnosis was that he died of paralytic dementia caused by syphilis.

Always frail, Theo suffered a life-threatening illness at age 19. At 25 he had bouts of headaches and malaise. At 29 he had been frightfully ill and six months later was painfully stiff to the point of paralysis. He consulted with doctors but the leg pains returned. Theo’s nightmares and hallucinations were incorrectly associated with a new cough medicine, most likely containing morphine or opium. Theo’s health deteriorated very rapidly and Johanna was obliged to face the fact that she couldn’t care for him at home.

Theo’s medical records reveal his very harrowing condition. Suddenly hospitalized in October 1890, a straitjacketed Theo was transferred from Paris to the Netherlands on November 17, 1890, where he ended his days. Doctors described Theo as agitated, confused with no notion of time and space, and unable to answer a single question coherently. He spoke in a undecipherable monologue of several different languages. Tearing at his clothes, he was unable to settle or calm down. Other symptoms pointed to paralysis. Medical records found within Wouter Van der Veen and Peter Knapp’s book Van Gogh in Auvers: His Last Days detail disastrously upsetting visits from Jo and Theo’s sister.

After the second of two epileptic seizures Theo didn’t regain consciousness. His heartbeat and respiration gradually weakened and died before midnight on January 25th, 1891. There was no post-mortem. He was buried in Utrecht.

We learn of the death of Theodore Van Gogh, the sympathetic and intelligent expert who worked so hard to make known to the public the works of the most daring independent artists of today, during the too short years that he remained director of the Boussod and Valadon house on Boulevard Montmartre. – Mercure de France, 1891.

Perhaps Theo contracted syphilis as a young man new to the big city. Visiting brothels was less taboo at this time and well-known men of the era: Baudelaire, Manet, Gauguin and Toulouse-Lautrec met their early end from syphilis. However, Theo’s waxing and waning symptoms were inconsistent with the progress of this disease.

It’s interesting to note that Vincent and Theo’s mental and physical disabilities were similar. Vincent alluded to a history of epilepsy in his mother’s family. There was a genetic disposition for insanity. Younger sister Wilhelmina spent the balance of her life in mental institutions. Cornelius van Gogh, the family’s youngest son, was another to commit suicide.

Jo dedicated her life to keeping the memory of the two brothers alive. Widowed at 28 with a remarkable collection of art, she took on the task of promoting the work of her brother-in-law, organizing and assembling his myriad art and letters.

Johanna Bonger, Theo’s widow with son Vincent Willem and 2nd husband, with Vincent Van Gogh’s art on the walls. Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

“…Theo taught me many things about art: no, I should say instead he taught me much about life…and aside from the child, he also left me another obligation: Vincent’s work, to make sure that it is seen and appreciated as much as possible. I am not without things to do, but I feel very alone and abandoned.” She remained a widow for 10 years and was married to Johan Cohen-Gosschalk from 1901-1912.

In 1914, Theo’s coffin was exhumed and reburied beside Vincent’s in the Auvers-sur-Oise graveyard. In 1926 Johanna Bonger-van Gogh died, leaving a brilliant inheritance of Vincent Van Gogh’s work, not only to her son, but also to the world.

Theo and Vincent’s grave in Auvers-sur-Oise © Hazel Smith

Lead photo credit : Theo van Gogh, 1878 via Municipal Photo Museum Amsterdam courtesy of Stedelijk Museum

More in Art History, Goupil & Ciel, Paris, Theo Van Gogh, Vincent van Gogh

REPLY