Life and Death at Charlie-Hebdo

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Though most Europeans have no idea who Charles “Sparky” Schulz was, his “Peanuts” characters are known all over the world. Until Wednesday’s events, French cartoonists Bernard “Tignous” Verlhac, Jean “Cabu” Cabut, Georges Wolinski and Philippe Honore were pretty much unknown outside of France… except to those who were told to “hate” them.

Though most Europeans have no idea who Charles “Sparky” Schulz was, his “Peanuts” characters are known all over the world. Until Wednesday’s events, French cartoonists Bernard “Tignous” Verlhac, Jean “Cabu” Cabut, Georges Wolinski and Philippe Honore were pretty much unknown outside of France… except to those who were told to “hate” them.

After an endless number of threats including a firebombing in 2011, the staff at Charlie Hebdo knew they were on the razor’s edge at all times. They worked daily under police protection. But, when faced with two fanatical individuals intent on a world of one religious belief, even an armoured door remains vulnerable. To help understand who the men and women behind their drawings really were, the New York Times filmed them at work in 2006 here. The document is subtitled in English. We can only hope it goes viral…

Hey, Mommy, who is “Charlie”?

Charlie Hebdo owes its origins, in part, to an Italian cousin, “Linus”, named after Shulz’s piano-playing, “Peanuts” character. In 1969 François Cavanna, the founder of Charlie-Hebdo, launched a non-satirical magazine called Charlie which reprinted numerous comic strips including that of Peanuts. Of course there were also other French satirical newspapers before Charlie-Hebdo, namely “Zéro” and “Hara-Kiri”, the latter founded by Georges (Professor Charon) Bernier and François Cavanna. But in reality the French satirical tradition began long before that, with writers such as Voltaire and Diderot.

It was a headline: “Tragic Ball in Colombay – One Dead” in reference to de Gaulle’s recent death in Colombay-les-deux-Eglises and to a tragic fire in a nightclub near Grenoble which had just cost the lives of 146 young people, that put an end to Hara-Kiri. The government forbid all publicity and the sale of the magazine to minors. François Cananna threw in the towel and created Charlie-Hebdo. He named the magazine in reference to de Gaulle and the Hara-Kiri incident, but also after Charlie Brown.

How it all began

Like most newspapers, Charlie-Hebdo had its share of “ups and downs”, some political, others for personal or financial reasons. What happened on Wednesday had its roots, not in France, but in the Netherlands in 2004.

Like most newspapers, Charlie-Hebdo had its share of “ups and downs”, some political, others for personal or financial reasons. What happened on Wednesday had its roots, not in France, but in the Netherlands in 2004.

The incident involved the assassination of a certain Theo van Gogh, son of the younger brother of painter Vincent van Gogh. Theo van Gogh was a film maker by trade. Blatantly Islamophobe and outspokenly provocative after the September 11th, 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center, Van Gogh was assassinated by Dutch-Moroccan Islamist, Mohamed Bouyeri, in November of 2004, crime for which Bouyeri is currently serving a life sentence without possibility of parole.

Shortly after the assassination, cartoonists at the conservative Danish newspaper, Jyllands-Posten, took it upon themselves to illustrate satirically – and just as blatently – certain of Theo van Gogh’s quotes. In 2005, the Danish government thwarted a plot by four armed gunmen intent on killing as many of the gazette’s journalists as possible. You can learn more here.

Charlie-Hebdo was firebombed shortly thereafter for reproducing the Danish gazette’s provocative illustrations. It was this free spirit and outspoken defiance, satirizing everything from political scandals to any sort of religious fanaticism, which would cost them their lives on Wednesday.

Post mortem

On Thursday morning, the day after the assassination, I arrived, as usual, at the local newspaper in Auxerre for our weekly English lesson. One of the staff stopped me on the way in and asked, “How do you say ‘Bonne Année’ in English?” “Happy New Year”, I answered, “But I’m afraid it’s really an UnHappy New Year?” Tears began streaming down my cheeks, with a dawning realization of just how deeply we had all been affected by Wednesday’s events.

On Thursday morning, the day after the assassination, I arrived, as usual, at the local newspaper in Auxerre for our weekly English lesson. One of the staff stopped me on the way in and asked, “How do you say ‘Bonne Année’ in English?” “Happy New Year”, I answered, “But I’m afraid it’s really an UnHappy New Year?” Tears began streaming down my cheeks, with a dawning realization of just how deeply we had all been affected by Wednesday’s events.

Saturday, January 10th, 2015. After a two-day manhunt covered Live on radio and TV world-wide, France suddenly awakens to memories of other murderous terrorist attacks, those in the Marais, rue des Roziers, in 1980, in a mailbox in front Tati’s cut-rate store in Montparnasse in 1986, in the St Michel métro station in 1995…

In two days nearly 5 million men, women and children, over 1.5 million in Paris alone, have flooded the streets to honor the seventeen victims of France’s three day tragedy. In Lyon alone over 300,000 people have turned out and here, in nearby Auxerre, an hour and a half southeast of Paris, over 10,000 marchers of all ages have gathered, in freezing weather, to pay tribute. It is France’s largest public demonstration since the Liberation of Paris at the end of WWII! Even more remarkable, it was echoed around the world!

A town like many others

After a half hour’s march, the procession in Auxerre has arrived in front of the City Hall. A man in his late fifties stands silently in the crowd. In his hands, one long-stemmed white rose.

After a half hour’s march, the procession in Auxerre has arrived in front of the City Hall. A man in his late fifties stands silently in the crowd. In his hands, one long-stemmed white rose.

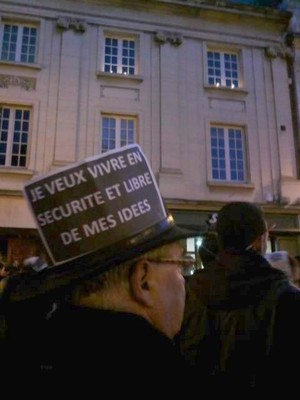

Next to him a gentleman listens solemnly, a sign on his black hat proclaims, “I want to live in safety and free to express my thoughts.” All around people of all ages: teenagers, families with children, many of them still in strollers, young couples holding hands, local merchants gather in silence.

Most everyone is dressed in black. Here and there a French flag reminds us that France is a “Republic”. From time to time, but rarely, a small group shouts “Je suis Charlie!” But this is a march, not a demonstration. Window sills are alight with candles and elderly people, those unable to take part directly, holding forth large “Charlie” signs, look down upon the procession as it passes below.

The assembly lasts over an hour. There are songs, “Amazing Grace”, “We Will Overcome” and, of course, the “Marseillaise”. There are poems by well-known French poets and an excerpt from a book by France’s late, and much missed, comic Pierre Deproges. The head of Auxerre’s mosque will be long applauded for his words of compassion and courage. A minute of silence and seventeen white balloons are released into the late evening sky in memory of the seventeen victims. The crowd turns and retraces its steps together, as silently as it has come.

You can’t kill a pencil

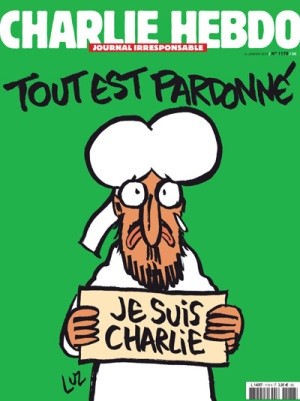

The last drawing of Charlie-Hebdo‘s editor Stephane Charonnier headlines “Still no Terrorist Attacks in France” Below the headline, a terrorist is saying, “Just wait, we still have till the end of January to extend our best wishes.” The front page chosen for the post mortem edition reads, “All is forgiven” and shows Mohamed holding an “I’m Charlie” sign.

If, ironically, the Kouachi brothers took shelter in the offices of a printing house just before their standoff with police, doubly ironical is the fact that, unbeknownst to brothers, Charlie-Hebdo was on the brink of bankruptcy. Totally dependent on subscriptions and newsstand sales, itwas selling roughly only half of its weekly publication and needed to reach 5,000 more sales a week just to break even.

If, ironically, the Kouachi brothers took shelter in the offices of a printing house just before their standoff with police, doubly ironical is the fact that, unbeknownst to brothers, Charlie-Hebdo was on the brink of bankruptcy. Totally dependent on subscriptions and newsstand sales, itwas selling roughly only half of its weekly publication and needed to reach 5,000 more sales a week just to break even.

Now, with the disappearance of its top contributors and its survivors hard at work in the offices of another of France’s progressive newspapers, Libération (a newspaper founded in the ’60s with the help of Jean-Paul Sartre) their work goes on. With 5 million copies of Wednesdays edition, 16 translations and distribution in 26 countries, the newspaper’s immediate future seems assured.

Third ironical detail, France is, as a rule, pretty much unsupportive of their police forces. On Sunday, when France’s CRS (State Police) cut through the millions of rallying Parisians in order to join the head of the rally, not only were they warmly applauded, but they were even embraced in a sort of “guard of honor” by the crowd. Many of those applauding rallied in protest against those same CRS, along those same Paris streets, in May of ’68.

Note that In Denmark the editor of the Jyllands-Posten decided to simply print a black front page and that certain of the representatives or State leaders locking arms in Sunday’s Paris rally were from countries which figure regularly on Amnesty International’s list of current Civil Rights offenders.

Charles Schulz was from my hometown in California. He was a kind, generous person. “Peanuts” popularity stems from Shultz’s understanding of just how complicated it is to survive our everyday contradictions. I try and imagine, instead of the Red Baron, a Snoopy disguised as The Prophet Mohamed, sitting on top of his dog house, reading the Koran to Woodstock and his angry bird friends and saying, “Stop acting like idiots! You can kill a journalist, but it takes more than an AK–47 to kill a pencil!”

Research Sources:

Photos sources:

Charlie-Hebdo

All other photos were taken by the author

More in Charlie Hebdo, French news, News in France