Gemma Bovery : Madame Bovary, C’est Elle

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

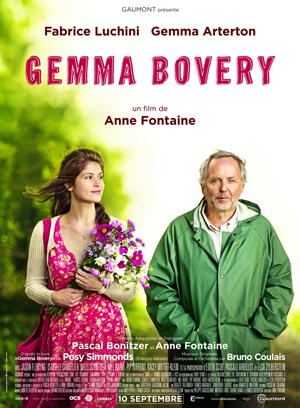

Gemma Bovery is lushly filmed but oddly constructed, a movie that tickles your senses while your brain wonders whether it’s all a botched cinematic soufflé. It mashes up an update of Flaubert’s novel and an English-French encounter à la A Year in Provence. Gemma Arterton and Jason Flemyng play an English couple who’ve decided to set up house in a deceptively idyllic-looking Normandy. Things get complicated when a Parisian publisher-turned-baker and Flaubert fanatic becomes infatuated with Gemma and convinces himself that her life parallels that of the original Madame Bovary.

Gemma Bovery is lushly filmed but oddly constructed, a movie that tickles your senses while your brain wonders whether it’s all a botched cinematic soufflé. It mashes up an update of Flaubert’s novel and an English-French encounter à la A Year in Provence. Gemma Arterton and Jason Flemyng play an English couple who’ve decided to set up house in a deceptively idyllic-looking Normandy. Things get complicated when a Parisian publisher-turned-baker and Flaubert fanatic becomes infatuated with Gemma and convinces himself that her life parallels that of the original Madame Bovary.

This is yet again another film where the French resurrect a gem from their culture to swoon over. But with the passage of time classics become sentimentalized—director Anne Fontaine loses sight of the fact that Madame Bovary was a harsh analysis of a bored, romantic bourgeoise. We not only lose the social criticism, but also the sense of the heroine’s character—in the update, Gemma isn’t really the subject. We’re never inside her head. Rather, she’s the voluptuously filmed object of Ms. Fontaine’s camera eye.

Gemma Bovery also belongs to another genre: the Fabrice Luchini film. Luchini is the exuberantly declaiming (but also self-parodying) John Barrymore of French cinema. He tends to turn his films into one-man shows in which he rages, waxes sardonic, deludes himself, and much more. In Gemma Bovery Luchini is a comic French Lear revving his libido for a romantic ideal that must remain unattainable.

Luchini plays Martin, the publisher who returned to his native Normandy to live with his wife in a rustic house and take up the family bakery. Martin hasn’t really obtained the peace of mind he’d hoped for. He feels himself moldering away while growing distant from his long-suffering (but still tart-tongued) wife. Gemma awakens his dormant libido, overturning “years of sexual tranquillity.” Desire oozes from every glance he gives Gemma and every word he speaks to her, and when she asks him to suck the venom of a bee that’s stung her on the lower back … you get the idea.

Luchini plays Martin, the publisher who returned to his native Normandy to live with his wife in a rustic house and take up the family bakery. Martin hasn’t really obtained the peace of mind he’d hoped for. He feels himself moldering away while growing distant from his long-suffering (but still tart-tongued) wife. Gemma awakens his dormant libido, overturning “years of sexual tranquillity.” Desire oozes from every glance he gives Gemma and every word he speaks to her, and when she asks him to suck the venom of a bee that’s stung her on the lower back … you get the idea.

Gemma and Charley are eager to repeat the Peter Mayle experience (albeit in Normandy, rather than Provence)—they adore the wonderfully sense-drenched French edibles, smellables, touchables. Yet they chafe at the difficulties of village life: the leaks, mice, broken cupboards. This gives Martin a chance to worm his way into their lives.

As Martin starts an obsessive friendship with the young Englishwoman, and observes the parallels between her and Madame Bovary, we wonder if he might be a crackpot projecting his delusions. His observations and projections may just be a self-fulfilling prophecy: his own actions play havoc with the couple’s life.

But just as we don’t perceive Gemma as a real person, we don’t have much of a sense of Charley’s character either, or their relationship. We do realize that life away from their native habitat is fraying the marriage. What tips the balance are two men who enter the picture (neither of them Martin, alas). We discover that there was a previous man in Gemma’s life, the archetypal married cad, who reappears. There’s also Hervé (Niels Schneider), the son of the owners of the village chateau. (The irony is that the real complication comes from Gemma turning back to her husband.)

But just as we don’t perceive Gemma as a real person, we don’t have much of a sense of Charley’s character either, or their relationship. We do realize that life away from their native habitat is fraying the marriage. What tips the balance are two men who enter the picture (neither of them Martin, alas). We discover that there was a previous man in Gemma’s life, the archetypal married cad, who reappears. There’s also Hervé (Niels Schneider), the son of the owners of the village chateau. (The irony is that the real complication comes from Gemma turning back to her husband.)

The most sharply observed scenes come from the movie’s intentional comic relief—the Franco-British couple that Gemma and Charley become friends with. Elsa Zylberstein is hilarious as a pretentious fashion slave who seems to have popped out of a house-and-gardens magazine to hire Gemma to re-decorate her home. Her husband is one of those English oafs who expatriate themselves in order to denigrate wherever it is they’ve expatriated.

While all the actors in Gemma Bovery do a serviceable job, there’s not much real acting in the film. There’s Luchini’s running commentary, but without the genuine interaction that acting needs. As with Woody Allen, age has made it increasingly implausible for Luchini to get the girl. When the romantic Martin is forced to be a voyeur or Platonic friend we feel both the comic and pained aspects of his predicament. It adds human depth to his performance, but also limits the drama.

There’s also Gemma Atherton’s camera-posing. To be fair, she does try to act, but because the director hasn’t written a full-bodied role for her, she seems to be just going through the motions. The rest of the cast isn’t quite there, either. Only Elsa Zylberstein’s comic performance really shines.

There’s also Gemma Atherton’s camera-posing. To be fair, she does try to act, but because the director hasn’t written a full-bodied role for her, she seems to be just going through the motions. The rest of the cast isn’t quite there, either. Only Elsa Zylberstein’s comic performance really shines.

Maybe Gemma Bovery should have been satiric from the start, rather than archly romantic (or romantically arch). In any case, the film abruptly lurches near the end to a completely different tonal register. The director’s sense of irony keeps things from falling apart, but barely; it’s in contrast to the sure-footedness of the original. That may be the difference not only between Fontaine and Flaubert, but between Flaubert’s era and our own.

Production: Albertine Productions/Ciné@/Gaumont

Distribution: Gaumont

More in film review, French film, Gemma Bovery