Palais-Royal: Around and About Paris

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 80 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

So: you are going to Paris. Whether this is your first trip and you don’t know Paris at all, or whether this is your umpteenth trip and you think Paris holds no more secrets, be wary and listen to what Victor Hugo had to say about his native city, which he knew at least as well as any of his contemporaries did: “He who looks into the depths of Paris grows giddy.” I couldn’t agree more with Victor Hugo. This is precisely why this quotation heads my book.

Don’t just rush to the Louvre and the Musée d’Orsay when you come to Paris. Put on your walking shoes and go into the streets. I hope the excerpts from my books will entice you to do so and help you glimpse both its hidden beauty spots and its secret nooks and stories, which Paris only unveils to those who are adventurous and en terprising enough to seek them out. The following excerpt is taken from the chapter on the 1st arrondissement, in the first volume of Around and About Paris, and is part of the third walk.

Guided historical walk at the Palais-Royal gardens

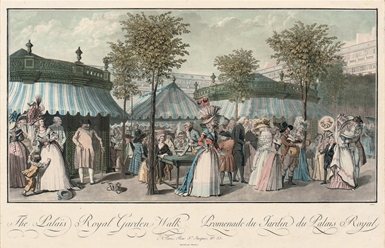

Turn left on rue de Beaujolais and left again to the Galerie de Beaujolais, leading to the gardens of Palais-Royal. You will enter a world of exquisite tranquillity where time has come to a standstill, a sleepy arcaded enclosure, shut off from the noisy streets around and graced with a Venetian touch. Despite the playful children and the chatty diners of an outdoor restaurant, a quiet secluded atmosphere prevails. Even Daniel Buren‘s striped columns, which har with the surrounding architecture and stone, and draw here weekend crowds, do not awaken it from its provincial drowsiness, particularly on weekday mornings. And yet, between 1784 and 1830 this was the bustling centre of both intellectual and dissolute Paris, lined with cafés and restaurants as well as game-houses and brothels. The mecca of prostitution, to which whores and courtesans came from all over Paris “faire le Palais,” as the saying went. Witness Casanova, who rushed here on his arrival in Paris.

When the palace was built for Richelieu it was known as le Palais-Cardinal. Richelieu bequeathed it to Louis XIII and after the latter’s death the royal family moved in. It was conveniently situated close to Mazarin‘s home on the neighbouring rue Neuve-des-Petits-Champs. To facilitate his rendezvous with Anne of Austria, a door was fitted into the wall which surrounded the palace. It proved handy in 1650, during the princely revolt of the Fronde, when the Queen and her two sons, the future Louis XIV and Philippe d’Orléans, escaped to Saint-Germain-en-Laye. Later Henrietta of France, the widow of Charles I of England, came to live here with her daughter, Henrietta of England, who would marry Philippe d’Orléans. She died in 1661 and Philippe d’Orléans married the princess Palatine, by whom he had one son, another Philippe Duc d’Orléans, who would become the celebrated Régent after the death of Louis XIV in 1715. He ruled over Paris till 1723, when Louis XV, aged 13, began to rule in effect.

It was during the Regent’s light-hearted reign that the Palais-Royal became notorious for its “soupers,” veritable bacchanalia. His grandson Philippe, the Fifth Duc d’Orléans and father of the future King Louis-Philippe, was in deep debt when he took over the Palais-Royal. He therefore built the arcades and their shops which he rented out, turning the establishment into a profitable business. Gambling houses and brothels opened up too, to ensure substantial profits. The Duke’s new line of activities was not to the taste of Louis XVI: “Cousin,” he said disdainfully, “you have turned shop-keeper and no doubt we shall see you only on Sundays.”

Philippe d’Orléans would have his revenge: in 1793, having sided with the Revolution, he became member of the Convention under the name of Philippe Egalité and voted for the death of his royal cousin (whom some claim he had hoped to replace). The guillotine, however, took charge of him too, only a few months later. The newly converted Palais-Royal was opened in 1784 to the satisfaction of all. Among its shops was a cutlery establishment at number 177, Galerie de Valois, which belonged to Monsieur Badin. Here on July 13, 1793 Charlotte Corday bought the knife with which she stabbed Marat in his bathtub the same day.

But the Palais-Royal was also the intellectual centre of the capital, studded with cafés where such prominent figures as Diderot used to sup and where dangerous new ideas were in progress. Diderot’s fictitious, beggarly, parasitical, yet so worldly Neveu de Rameau tells us that the celebrated café La Régence (on the site of the present number 161, rue Saint-Honoré) was the mecca of chess players. On wet days, when he could not meditate on one of the benches in the garden, the musician Rameau’s nephew would step into La Régence and watch a good game of chess. The chessboards were rented by the hour and cost more at night when a candle had to be fixed on either side. “Paris is the place in the world, and the Café de la Régence the place in Paris where the game is best played,” he tells us. Now this was no fiction. In fact, François André Danican-Philidor, composer and co-founder of the Opéra-Comique, and also world chess champion, would take on the world’s best chess players simultaneously at La Régence, and beat them one by one mercilessly. His Analyse du jeu des échecs that he published in London when aged only 22, remains a classic.

Diderot’s preference, however, went to Légal ‘the deep’, as he expressed it via his hero. Philidor ‘the subtle’ annoyed him with his chess activities. He thought he should develop his musical talent rather than devote his time to simultaneous blind games, out of vainglory, “pushing little wooden pieces on a chessboard,” as he told him bluntly. In 1794 Napoleon, an excellent chess player too, shared a wretched existence between a dump of a hotel in today’s rue d’Aboukir (in the 2nd arrondissement), and Café de La Régence where he spent hours moving pieces on a chessboard, rehearsing for the strategic showdown soon to come.

During the Restoration of the monarchy that followed Napoleon’s downfall, the Palais-Royal became the scene of bellicose duels. Having fought the rest of Europe, the French now set about killing each other off wholeheartedly. The Monarchists assembled in the Café de Valois, the Bonapartists and the Liberals in the Café Lemblin. The slightest provocation ended up with a fatal confrontation. An inhabitant of rue de Montpensier related how between the years 1815 and 1820 he had been woken up over 20 times by the groaning victims of the political clashes. In Paris it needn’t be only politics that triggers passionate, violent arguments. At Le Caveau the heated conversations and verbal sparring centred around music and gave way to impetuous confrontations between the partisans of the Italian Piccini and those of the German Gluck! However quarrelsome a Frenchman may be, his palate and stomach will always bring him back to line, and good fare was to be found in plenty at the Palais-Royal. Le Café de Chartres, at numbers 79 and 82, Galerie de Beaujolais, another Monarchist stronghold, served a set menu of vermicelle et poitrine de mouton aux haricots.

During the Restoration of the monarchy that followed Napoleon’s downfall, the Palais-Royal became the scene of bellicose duels. Having fought the rest of Europe, the French now set about killing each other off wholeheartedly. The Monarchists assembled in the Café de Valois, the Bonapartists and the Liberals in the Café Lemblin. The slightest provocation ended up with a fatal confrontation. An inhabitant of rue de Montpensier related how between the years 1815 and 1820 he had been woken up over 20 times by the groaning victims of the political clashes. In Paris it needn’t be only politics that triggers passionate, violent arguments. At Le Caveau the heated conversations and verbal sparring centred around music and gave way to impetuous confrontations between the partisans of the Italian Piccini and those of the German Gluck! However quarrelsome a Frenchman may be, his palate and stomach will always bring him back to line, and good fare was to be found in plenty at the Palais-Royal. Le Café de Chartres, at numbers 79 and 82, Galerie de Beaujolais, another Monarchist stronghold, served a set menu of vermicelle et poitrine de mouton aux haricots.

Today, its descendant Le Grand Véfour has abandoned homely fare: with its wealth of decorations and choice dishes it is one of the best restaurants in the capital, and as such was targeted by Leftists to be blown up in December 1983. At number 83, Le Véry created a sensation when it first opened, being the first Parisian establishment to offer meals at fixed prices, high enough nonetheless to ensure a select clientele. Among them was the illustrious painter Fragonard, who actually expired here while savoring a sorbet. In 1830 the “bourgeois” King Louis-Philippe ascended the throne. A “middle-class” puritan, he decided to close down this seat of vice (and of political threat: after all, the French Revolution had also been plotted here).

Some Parisians held on to the place for another generation, and at the time of Balzac it was still a popular promenade where art and vice mingled. The more fashionable Parisians had migrated to the new axis of pleasure, les Grands Boulevards, further north; some frequented both. By the time Colette was living at 9, rue de Beaujolais, and Jean Cocteau at 36, rue de Montpensier, the Palais-Royal had become a closed world and assumed its present aspect of outdated serenity, as described by Colette: “In the mornings we went out for a breath of fresh air—cat, bulldog and me—on the garden chairs, uncomfortable armchairs of venerable age […] I like to think that a magic spell preserves, at Palais-Royal, everything that collapses and lasts, everything that crumbles and doesn’t alter.” She goes on to describe its nameless, silent citizens who followed a code of mysterious mutual courtesy: the elderly lady leaning on her stick, the gentleman cultivating little cacti on his window sill, the other gentleman in straw slippers on his early morning walk, or the earnest little boy who might one day lay a marble in the palm of your hand. There was also a venerable lady who might one day read out to you the ode she had written to Victor Hugo.

Some Parisians held on to the place for another generation, and at the time of Balzac it was still a popular promenade where art and vice mingled. The more fashionable Parisians had migrated to the new axis of pleasure, les Grands Boulevards, further north; some frequented both. By the time Colette was living at 9, rue de Beaujolais, and Jean Cocteau at 36, rue de Montpensier, the Palais-Royal had become a closed world and assumed its present aspect of outdated serenity, as described by Colette: “In the mornings we went out for a breath of fresh air—cat, bulldog and me—on the garden chairs, uncomfortable armchairs of venerable age […] I like to think that a magic spell preserves, at Palais-Royal, everything that collapses and lasts, everything that crumbles and doesn’t alter.” She goes on to describe its nameless, silent citizens who followed a code of mysterious mutual courtesy: the elderly lady leaning on her stick, the gentleman cultivating little cacti on his window sill, the other gentleman in straw slippers on his early morning walk, or the earnest little boy who might one day lay a marble in the palm of your hand. There was also a venerable lady who might one day read out to you the ode she had written to Victor Hugo.

Jean Cocteau was more than just a neighbor, even though he dropped in on Colette en voisin.” He was a friend and admirer who called her “an ink fountain.” Today’s arcades are as peaceful as then, lined with ravishing outdated shops, and the lovely gardens are still an oasis in the heart of a congested city, “La campagne en plein centre de Paris,” to quote Cocteau once more.

More in Bonjour Paris, French history, Paris history, Paris restaurants, Paris tourism, Paris writers