Street Art from the Belle Epoque: Illustrated Posters at Musée d’Orsay

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

If I could choose only one item to remind me of Paris, I think I’d pick a poster, perhaps an iconic Toulouse-Lautrec advert for a concert-bal at the Moulin Rouge or one of Alphonse Mucha’s stylish representations of Sarah Bernhardt. So I was very drawn to the exhibition, showing until July 6th at the Musée d’Orsay, which promised a journey through the “golden age of illustrated posters.” It turned out to be much more than a chance to enjoy some of my favorite pieces from the Belle Époque, along with lots I hadn’t seen before, but also an opportunity to understand how they began life as a 19th-century version of street art, both an artistic phenomenon and a vehicle for social and political change.

The exhibition’s title, L’Art est dans la rue (Art is in the Street) makes clear that this art form was often first seen in the streets of Paris, plastered onto walls or billboards and an early exhibit, an oil painting from 1882 called L’Étameur, sets the scene. It depicts a woman mending pots and pans in a little street booth with a haphazard selection of posters stuck up all over the wall behind her. It shows how posters brought art out of the galleries and onto the streets, democratizing it. Ordinary people would be seeing the works, those producing them would adapt their designs to catch their eye and the results would better represent the society of the time than anything to be found in more formal settings.

Poster of Sarah Bernhardt as Joan of Arc. Photo: Marian Jones

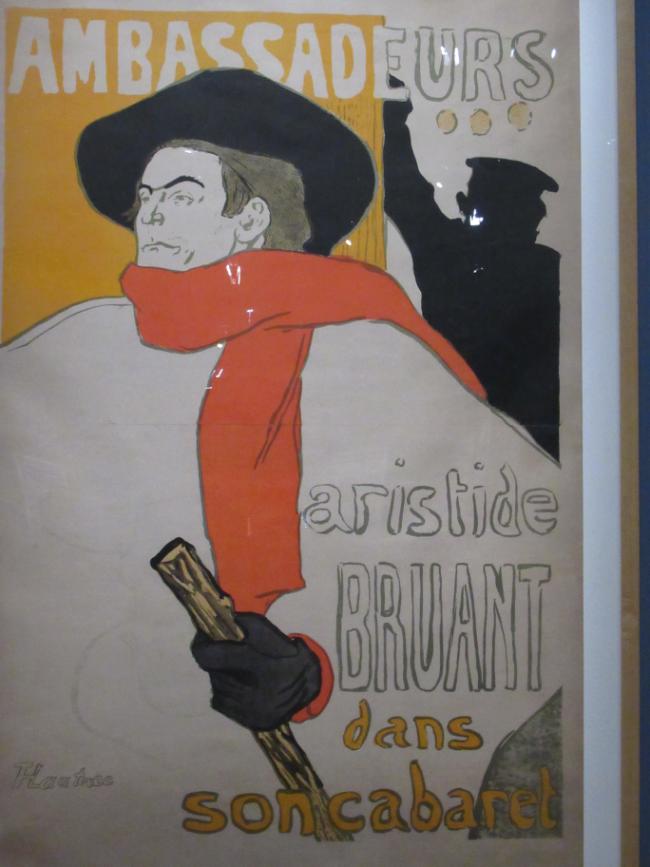

Posters, said an early text in the exhibition, were nothing new, even in the 19th century. Francis I had posted royal decrees for all to read in 1539 and printed materials – posters and pamphlets – were produced during other key events, such as the revolution. But it was in the mid-19th century, when color printing became possible thanks to the new technique of lithography, that things really took off and suddenly businesses saw the possibilities of this exciting new advertising medium and began to commission posters. Explanatory exhibits include a printing machine, a photograph from 1899 showing the inside of a printing works and a fascinating series showing how Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s well-known poster for the Ambassadeurs Theatre was printed in successive versions, each adding one new color.

Suddenly bill-posters, with their ladders, brushes and pots of paste. were a common sight on the streets of Paris, sticking up posters wherever space could be found. Some were employed by shops and theater owners, others posted during election campaigns and the result was a colorful mix of ideas jostling for attention. The art critic Roger Marx described the effect all this had on Paris as the creation of an “open-air museum … where the brilliant collides with the mediocre, where the exquisite rubs shoulders with the coarse, where the spiritual rubs shoulders with the absurd.”

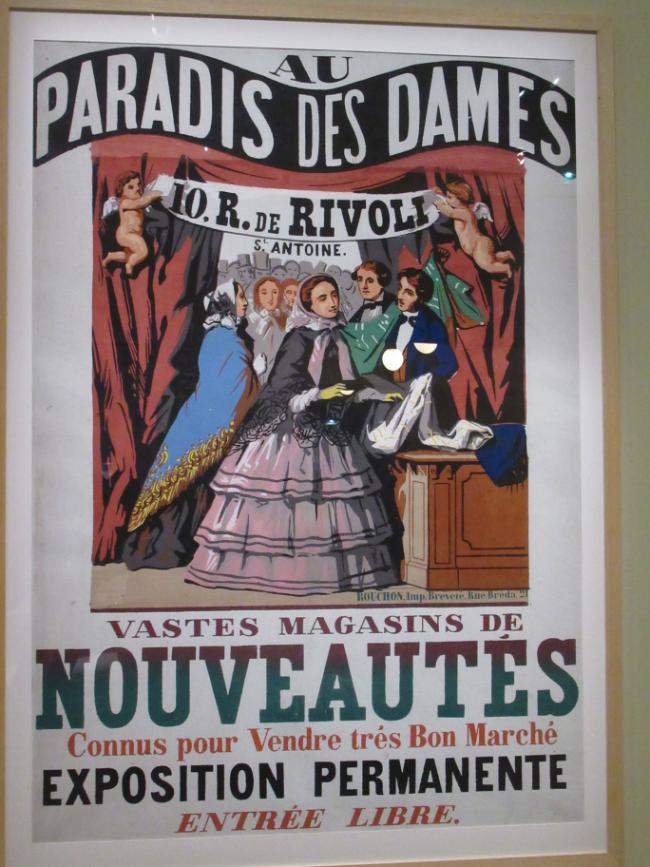

Au Paradis des Dames poster, 1856. Photo: Marian Jones

The writer Émile Zola called the new department stores “cathedrals of consumption” and their owners were quick to see the advantage of advertising their wares in this attention-catching new way. As early as 1856, posters were appearing for Au Paradis des Dames on the Rue de Rivoli, enticing customers to visit and see – for no cost! – the wares on offer at the vaste magasin de nouveautés (vast shop of novelties). The industrial revolution meant goods could now be mass-produced and posters would help the shops advertise them to large numbers of customers.

Chocolate Menier poster. Photo: Marian Jones

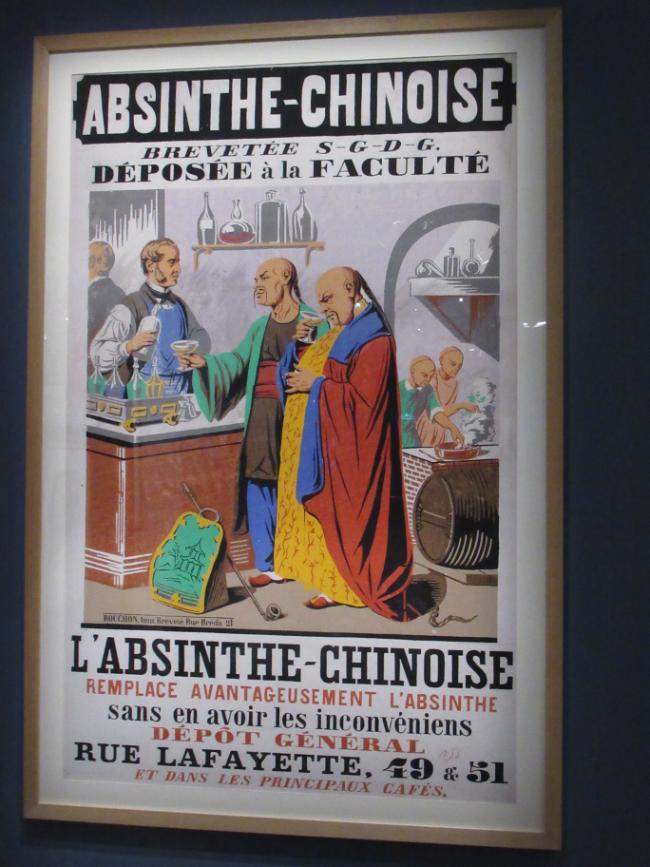

There was quirkiness too, for example a poster extolling the virtues of “Chinese absinthe” and promising a product as good as the real thing, yet “without the disadvantages.” New strategies were thought up which we can still see in today’s marketing techniques. A poster advertising Chocolat Menier featured a child in order to appeal to the female customers who were beginning to have more purchasing power and perhaps also to stimulate a little of what we would call “pester power” today! The artist also found a clever way to repeat the name of the product by showing the little girl writing out the product’s name more than once.

Chinese absinthe poster. Photo: Marian Jones

Theaters and cabaret venues made extensive use of posters and there are lots of charming examples in the exhibition, including a number designed by the prolific artist and lithographer Jules Chéret. His adverts for the Élysée Montmartre and the Folies Bergères fizz with the exuberant atmosphere of the Belle Époque. They will have been displayed all around the buzzy Grands Boulevards area, contributing to the gaiety of the city and many of them still serve today as iconic images from the era. Who doesn’t immediately recognize Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s poster for Le Chat Noir?

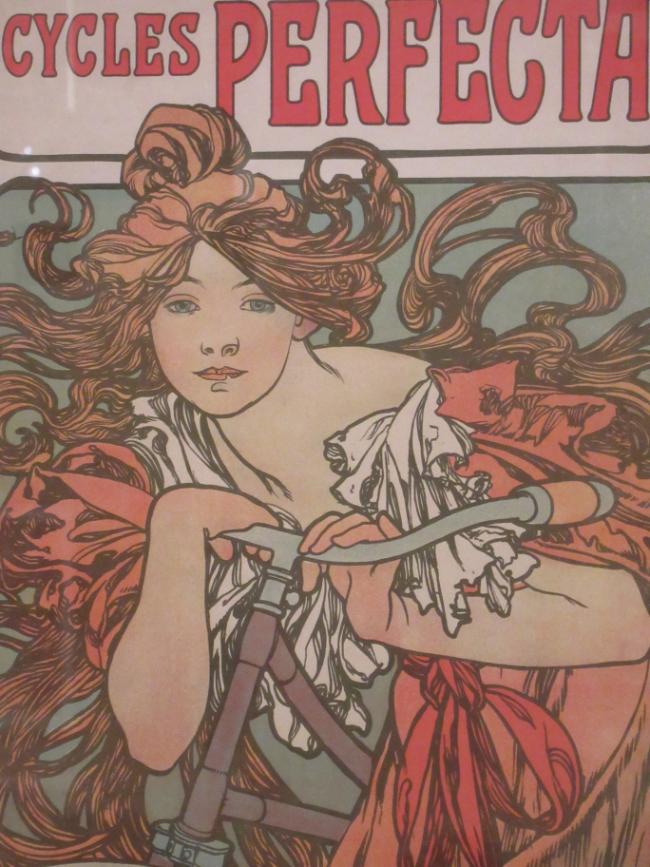

Popular artists of the day often worked with actors and cabaret stars. Lautrec’s depiction of La Goulue, the flamboyant dancer who made her name at the Moulin Rouge, is here and so is the work of another artist closely linked to the Belle Époque, Alphonse Mucha. There’s a whole selection of the pieces he created for productions starring the actress Sarah Bernhardt including Jeanne d’Arc, Medea and La Dame aux Camélias. This collaboration was a forerunner of modern PR techniques, the stunning posters contributing to, as one caption puts it, “the invention of an icon.”

It all felt very modern and “of-the-moment.” The latest trends found their way onto posters, whether that was Mucha’s colorful design for Cycles Perfecta or the posters advertising the new tourism industry, made possible by the expansion of the railways. One colorful design for the Paris-Lyon-Méditerranée line advertises a trip to Lake Maggiore in Italy. The growing interest in faraway cultures can be seen in a Folies Bergère poster from 1895 advertising Awata, “the famous Japanese juggler.” The craze for collecting the posters themselves, known as affichomanie, or “poster-mania” in English, is represented by a stand in which a proud owner could display posters bought to keep as works of art.

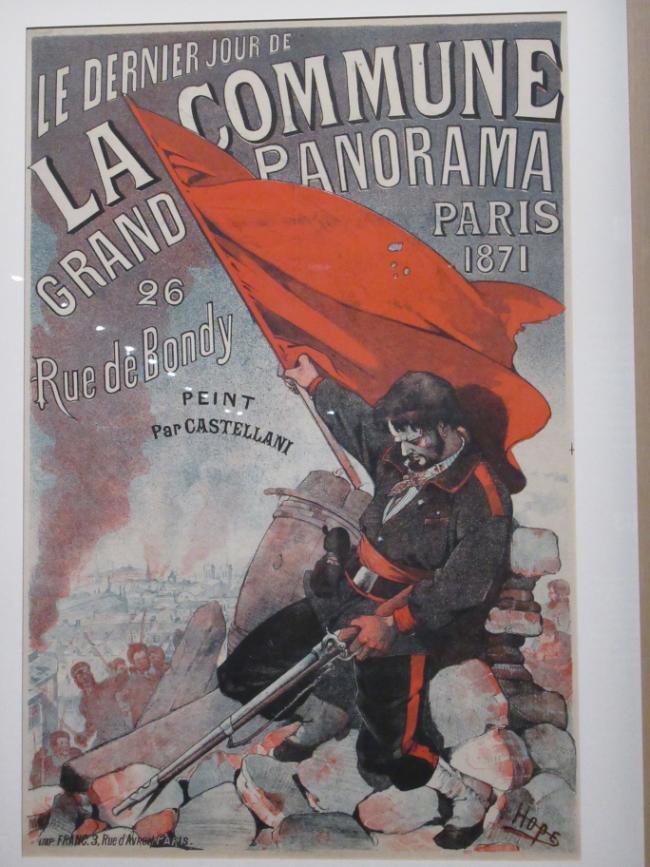

After the Freedom of the Press Act was passed in 1881, more liberal subject matter was permitted, often highlighting social or political concerns. In the essay L’Art dans la Rue (Art in the Street) from which the exhibition takes its name, the Belgian architect Frantz Jourdain wrote about the social responsibility artists had because “people learn as much in the street as they do in the classroom.” The posters-with-a-message on display include one depicting the last day of the Paris Commune and one advertising Lanterne, a fiercely anti-clerical newspaper. Posters were used by trade unions and political groups and one of the last on display is a government poster from 1916, urging young men to fight for their country with the call “On les aura” (‘We’ll get them’).

Last Day of the Commune. Photo: Marian Jones

It makes a fitting end to the story, for it was with the onset of World War I that the Belle Époque came crashing to a halt. This exhibition explains much about the origins of street art, both artistically and for its role in social commentary. It’s also a fascinating trip back to the legendary period when Paris led the world in style and glamour, an era these glorious posters illustrate in enlightening and colorful detail. Do go if you can.

DETAILS

Art is in the Street

Musée d’Orsay until July 6th

Full rate €16. Concessions €13

9:30 am – 6 pm

Closed on Mondays

Late night on Thursday until 9:45 pm

Lead photo credit : L'Etameur. Photo at the Orsay exhibit: Marian Jones

More in Alphonse Mucha, belle epoque, Orsay, posters, Toulouse-Lautrec