Leonardo Da Vinci Laid Bare at the Louvre

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Ever heard Leonardo da Vinci’s prediction that one day humans would master flying and be able to sail through the sky like birds? If not, perhaps you should head to the Louvre for the biggest ever Leonardo da Vinci exhibition in history before it closes on February 24th – and see for yourself just what his feverish imagination compelled him to sketch. With completely free late night opening slots scheduled for the last three days, there’s no excuse not to check it out.

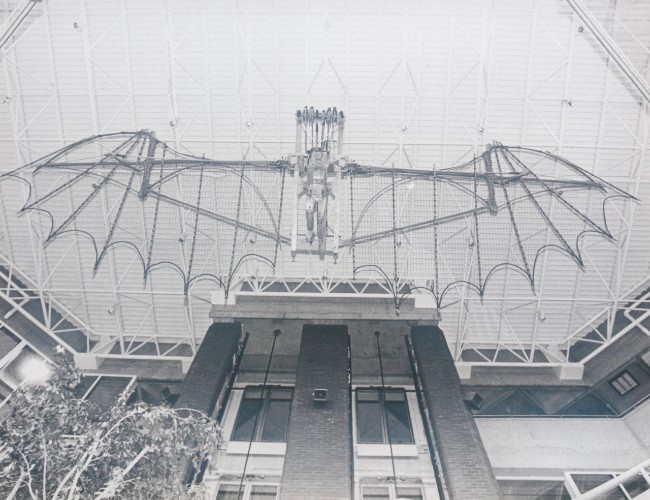

The uninitiated dismiss Leonardo da Vinci as a painter alone, but he was also an inventor, a military engineer and a royally commissioned entertainer for the French King — not to mention, of course, a fantasist of comedic proportions, tightroping that fine line between genius and insanity. One of his favorite inventions, for example, inspired by the anatomy of birds and bats, envisaged men launching themselves into the air strapped to a giant pair of mechanical wings. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this particular “flying machine” prototype quite literally never got off the ground, although his failures never dampened his fiery imagination.

Leonardo Da Vinci Flying Machine

After all, every part of modern life initially began as an idea in someone’s mind, from the architecture of a house to the design of the shoes on our feet. As the adage goes, without the dreams there is no reality — and Leonardo da Vinci was a perfect example of this. He designed an early version of the scuba suit back in an era when few had ever contemplated breathing underwater. He created a prototype for a robot which would later be brought to life, based on his exact sketches, by a NASA scientist. He even turned his talents to warfare, planning logistics for tanks and a machine gun before such weaponry had ever existed.

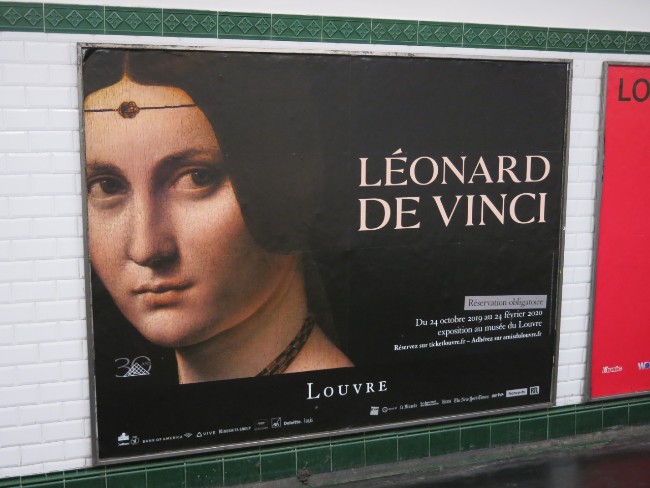

Metro poster advertising the exhibition

The exhibition at the Louvre takes a closer look at Leonardo da Vinci’s life and legacy, with paintings and sketches that depict everything from the aforementioned inventions to scenes of political life in his native Florence. Adding a touch of technology to the displays, a feature enables guests to see the Mona Lisa’s every detail projected through a virtual reality headset.

Infrared reflectograms of the Belle Ferronniere by Leonardo da Vinci

Arriving hot on the heels of the 500th anniversary of Leonardo da Vinci’s death, there could scarcely have been a better time to launch the tribute, which has been 10 years in the making. However, owing to fierce Italian opposition, it almost never went ahead. Paintings that would have played a starring role in the exhibition were withheld and loan agreements cancelled, while tensions between President Macron and nationalist groups across the border reached an all-time high. Those seeking symbolic possession of his legacy had argued that Leonardo da Vinci belonged to Italy and had “merely died in France”. Plus in those all-important final years before he captured the heart of the French King and was summoned to the Loire Valley, carrying the Mona Lisa and The Last Supper in his battered satchel, it seemed as though he had been an Italian loyalist too. A former friendship with the Duke of Milan, Ludovico Sforza, had led to the pair plotting how best to annihilate the French in battle. Consequently, some 400 years before armored tanks were first introduced on the battlefield, Leonardo da Vinci produced sketches for them — chariots shrouded in sheet metal, with slits in the sides from which to fire.

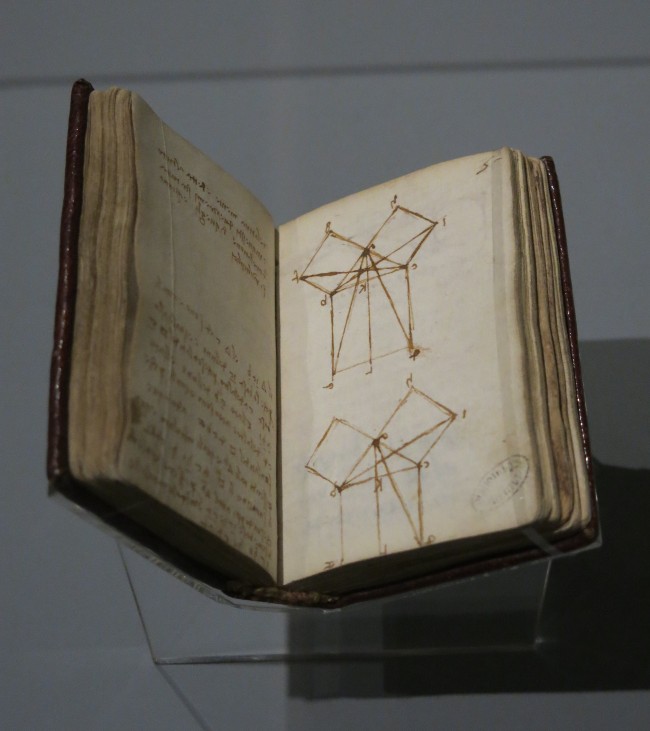

Sketches from Leonardo da Vinci’s Notebook demonstrating Pythagoras’ theorem

On another weapon-led occasion, 80 tons of bronze — originally intended for use on a horse statue that the Duke had commissioned Leonardo da Vinci to create — ended up being misappropriated by the royal for the construction of weaponry instead. This led to taunts from art rival Michelangelo, mocking the perception that the royal family had rejected his work. ‘Make Art, Not War’ seemed to have fallen on deaf ears in this case. Ultimately, the seemingly bloodthirsty friendship between the genius and the Duke ended when the latter was handed over to France in 1500 during the Treason of Novara.

Entrance hall of the Leonardo da Vinci exhibition at the Louvre

Amusingly, however, King Louis XII seemed to hold few grudges. He offered Sforza a soft imprisonment in a chateau in Berry, with free reign of the grounds, access to a royally approved doctor when he fell ill and permission to receive visitors too. The former Duke was perhaps regarded as more of an ornament for his collection than a genuine prisoner of war. The King’s successor, Francis I, was equally liberal about the then deceased, recalling gratefully how Sforza had commissioned the legendary Last Supper. By 1517, military affiliations seemingly firmly forgotten, Leonardo da Vinci would end up living on French territory.

Saint John The Baptist – one of the paintings that can be seen at the Leonardo da Vinci exhibition at the Louvre

Fast forward to 1911 and political tensions over Leonardo da Vinci would rise between France and Italy yet again, when a fellow Italian, Vincenzo Peruggia, seized the Mona Lisa from the Louvre, smuggled it across the border and attempted to sell it. When he was caught red-handed, the burglar was defiant and unapologetic, calmly stating that he had simply brought the masterpiece “back home” where it belonged. Although reclaiming a Renaissance treasure for his homeland saw him sentenced to jail time, some saw him as a patriotic hero who had not deserved capture at all.

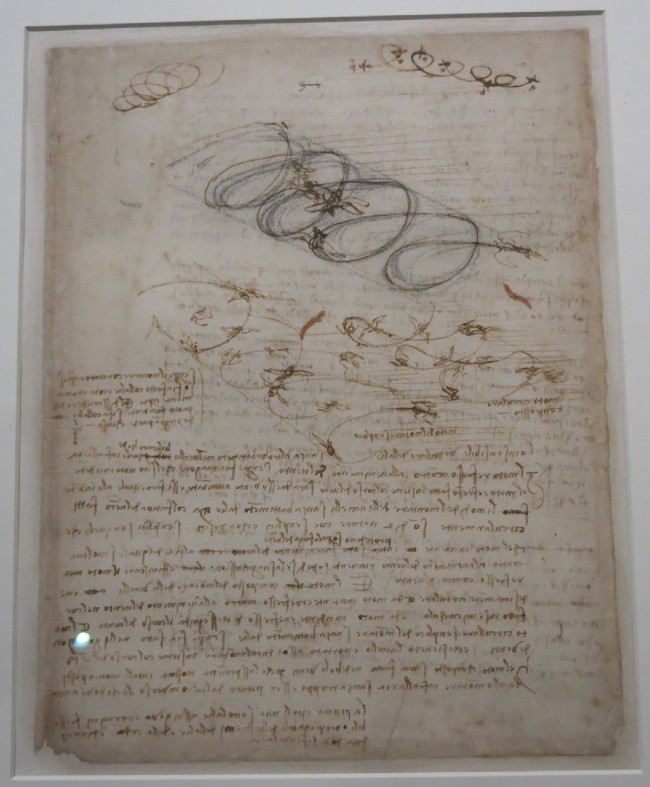

A sample of Leonardo da Vinci’s sketches

While the history of centuries past remains long forgotten by many, far-right Italian groups have continued the debate over where Leonardo da Vinci’s greatest works belong. In spite of the last-minute legal battles and the fact that legendary paintings such as the original version of Salvator Mundi — the most expensive piece of artwork ever auctioned — never made it into the exhibition, plenty of other visuals await. One believed to be Leonardo da Vinci’s first ever piece of art, featuring a river scene near Florence, has been loaned by the Ufuzzi Gallery, while the rare anatomy piece Vitruvian Man — most often kept under lock and key at the Gallerie dell’Accademia of Venice — also makes an appearance. Although the Louvre itself admits the selection of paintings is “small”, there are numerous sketches and scribblings from his personal notebooks too – and the intimacy of these exhibits up close justifies a visit.

The Mona Lisa

If this small slice of history has piqued your appetite for the exhibition, the details are below. Afterwards, anyone minded to follow in the footsteps of the infamous Mona Lisa thief — virtually, of course — can travel to the Phobia Escape Game rooms, which allow guests to legally “break into the Louvre”. The mission gamers are challenged to decipher Da Vinci’s secret messages, find the hidden Holy Grail and escape without triggering the alarm and getting cornered by the cops. Easily accessible from the Louvre within 15 minutes by car or less than 30 minutes by metro, it adds a heart-racing interactive element to an artistic experience.

Promo photo of the Da Vinci Escape Room

The Leonardo Da Vinci exhibition runs until February 24th at the Louvre.

Open every day (except Tuesday) from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m.

Night opening until 9:45 p.m. on Wednesday 19th, plus FREE night opening ALL night from February 21st to 24th – slots between 9pm and 8.30am.

Métro Station: Palais-Royal Musée du Louvre (lines 1 and 7)

Find tickets at: https://www.louvre.fr/en/leonardo-da-vinci

The Phobia Escape Game Rooms (open 9:30am to 11:30pm, seven days a week) are located at 127 rue Jeanne d’Arc in the 13th.

Metro Station: Nationale (line 6) or Campo-Formio (line 5)

Leonardo da Vinci sketches at the Louvre

Lead photo credit : Facade advertising the Leonardo da Vinci exhibition at the Louvre

More in Leonardo da Vinci, Louvre