After 125 Years the Brothers Lumière’s Invention Keeps Shining, But For How Much Longer?

One hundred and twenty-five years ago, the Brothers Lumière, Auguste and Louis, displayed their new invention to the general public at the Grand Café on the Boulevard Capucines in Paris. To put things into historical perspective, 1895 was before the Wright brothers’ flying contraption, before Henry Ford’s Model T, before television and commercial radio. Yet the invention they called cinema would not only revolutionize the world over the decades but is still at the epicenter of global culture. The Lumières’ cinema didn’t appear out of thin air, of course. It derived from the convergence of different technologies: photography, flexible film, persistence of vision gadgets such as flip-cards, and projectors that had been around since the magic lantern days.

Auguste and Louis were born in Besançon, in 1862 and 1864, respectively, while the American Civil War was still raging on the other side of the Atlantic. Their father had been in the photography business, and both brothers joined the family firm. Auguste took over its management, while Louis, a physicist, helped develop the photographic process. They moved to moving-picture film, working on both the film stock (introducing the system of perforated film passing on sprockets) and on the hardware. One of their early inventions, the Cinématographe, was a device that served as both camera and projector.

The Cinématographe Lumière at Institut Lumière. Image credit: Wikipedia,Victorgrigas (CC BY-SA 4.0)

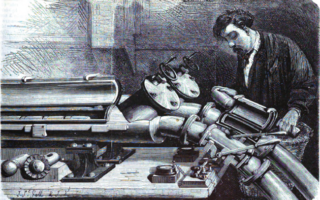

They took out numerous patents, but they weren’t alone. Inventors were working independently but simultaneously in Europe, England, and the United States, and myriad patent battles would rage for years. The brothers’ biggest rival for movie claim to fame was the American Thomas A. Edison, who invented the Kinetoscope several years before the Lumières’ cinema, in 1889 (or possibly 1890). The Kinetoscope was a peepshow device in which viewers looked into a small viewing screen and cranked the film by hand. It was antithetical to the idea of the cinema, an individual viewing of a bite-sized moving picture rather than a collective experience of a larger-than-life image.

Edison’s Kinetescope, which initially became popular in carnivals and peepshow parlors, was made obsolete overnight by the worldwide spread of the projected movie developed by the Lumières. A century later, however, an increasing number of people watch films on tablets, smartphones and other devices that have more in common with the Kinetoscope than the grand movie palaces that brought the public together by the thousands.

The Lumière brothers are not only renowned for the mechanical achievement of the cinema, but also for what is referred to nowadays as “content”. They made many short films, often barely half a minute long, for their new invention, films that were essentially reality-based documentaries. L’Arrivée du Train sometimes caused spectators to run away from the unfamiliar illusion of an on-coming locomotive. La Sortie de l’Usine Lumière (literally Coming out of the Lumière Factory) depicted workers employed by the brothers, while other films showed a blacksmith (Le Forgeron) and horseback vaulters (Le Voltige). These films offer a vivid record of a momentous time—the turn of the 19th to 20th centuries. This reality-based cinema was the ancestor not only of modern documentary filmmaking, but of cinema verité, neo-realism, the French New Wave and even American indie films.

That tendency was answered by their countryman, Georges Méliès, who with Voyage to the Moon and other works inaugurated the other pole of motion-picture art, the special-effects-laden fantasy. Hollywood conquered the globe with its American version of film fantasy (with loads of global talent contributing). Though it now has competition from Asia and Latin America, the Hollywood superhero franchise is the world-beater of our day. The director Martin Scorsese recently wrote an essay decrying the superhero genre, saying that it wasn’t genuine cinema, that it was more akin to that other prevalent form of contemporary entertainment, the video game.

But Scorsese has also made headlines by making The Irishman for Netflix. The rationale was that the platform gave him carte blanche to spend an enormous sum on the film’s production. Why so much money for a movie about aging gangsters? One reason was the tech used to “de-age” Robert de Niro and Al Pacino. Perhaps that puts Scorsese closer than he’d like to admit to the Georges Méliès brand of filmmaking (his film Hugo, after all, featured Méliès as a character). A film dependent on FX and money, closed off from the public who don’t subscribe to a digital platform, made to be seen on TV or other devices, may result in a new form that’s a hybrid of Edison and Méliès: call it the netflick. It sure isn’t what the Lumière brothers had in mind. But then the brothers never thought their novelty would amount to much. Their real dream? Making the perfect color photograph.

Many of the Lumière Brothers films can be viewed on YouTube. The Institut Lumière, housed in the brothers’ former residence in Lyon, is not only a museum dedicated to their life and work, but also a veritable cinemathèque with many exhibits and screenings. See http://www.institut-lumiere.org for more details.

Lead photo credit : Voyage to the Moon. Image credit: Flickr, Breve Storia del Cinema. Public domain

REPLY