And Then There Was Cinema: An Illuminating Exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

About 130 years ago, the merest cosmic blink of an eye, a new art form was born: cinema, the Seventh Art. The French rightfully take much credit for its creation. The Lumière Brothers invented the earliest cameras and projectors, inaugurated public exhibitions of film projections, and pioneered the documentary film, while Georges Meliès essentially founded the fantasy film genre. They were not the only ones, of course. Cinema was one of those new developments that came about in several places simultaneously and independently: There was Thomas Edison in the U.S. and others in Great Britain. Likewise, cinema was the fruit of synthesizing several technologies: photography, flexible film, magic lantern projection, persistence of vision novelties that gave the illusion of “moving pictures”.

The exhibit called Enfin Le Cinéma! (literally “Finally the Cinema!”) at the Musée d’Orsay takes an interesting and original perspective on the creation of the movies. We get the expected timeline and the depiction of early technology, machines like the Praxinoscope, Phéénakistiscope, Polyorama and Mégaléthoscope, as well as projected loops of haunting film clips from the turn of the 19th century showing a Paris that has vanished. On this level, the exhibit is good but could have been better, more clearly chronological. Also, though, we see some early filmmaking apparatuses, we would have appreciated functional replicas to show how they actually worked.

Le Pont de l’Europe, Gustave Caillebotte. Musée d’Orsay

What the Musée Orsay does best is something very different. It highlights the intellectual, social and cultural developments that were instrumental in turning what could have been just a carnival attraction into a revolutionary art form. This approach is more up the museum’s allée: similar to how its permanent collection combines works of genius by artists who were marginalized in their time and the more conventional portraits and other paintings that defined their society, and were a kind of contrast agent for the geniuses to struggle against. (For those who’d like an exhaustive, but probably exhausting, course in 19th-century visual culture, the basic entrance ticket, at 16 euros, covers both the exhibit and the permanent collection.)

Saint-Germain-des-Prés (C) Musée d’Orsay

One of the key elements the exhibit explores is the idea of new perspectives. The construction of tall buildings, and also balloons and airships, gave the public a new bird’s-eye vista of their physical surroundings. These were first exploited in paintings and photos, for example depicting views from the Eiffel Tower. In a different way, the proliferation of construction, beams and girders led to fragmentary views (for example, part of the composition in Gustave Caillibotte’s Le Pont de l’Europe consists of perspectives through the criss-crossing iron supports of a bridge). These fragmentary views were similar to (and sometimes intentionally replicated by) the view through the camera lens.

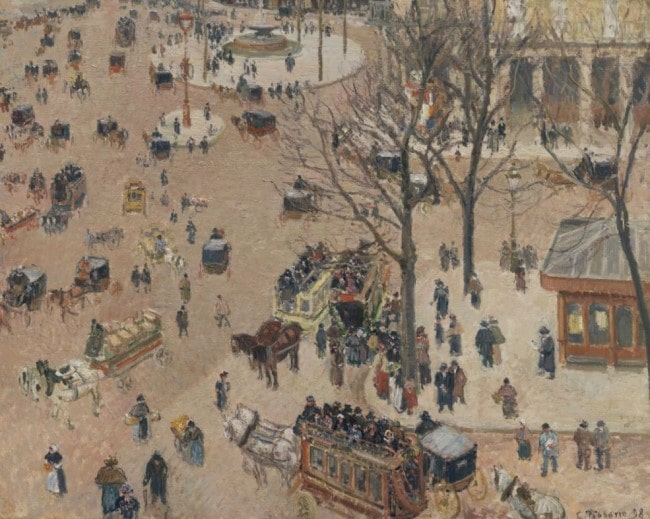

A second element was the new density and dynamism of the urban scene, resulting in an interest in crowds and images that caught figures on the cusp of movement and action. While the traditional arts (or the innovators among them like Camille Pissarro) could give a powerful inkling of the surge of people in the city, it was the early cinema that best portrayed humanity in action, like the Lumières’ documentary footage of workers streaming out of a factory.

Auguste Rodin, Pygmalion et Galatée (C) Musée d’Orsay

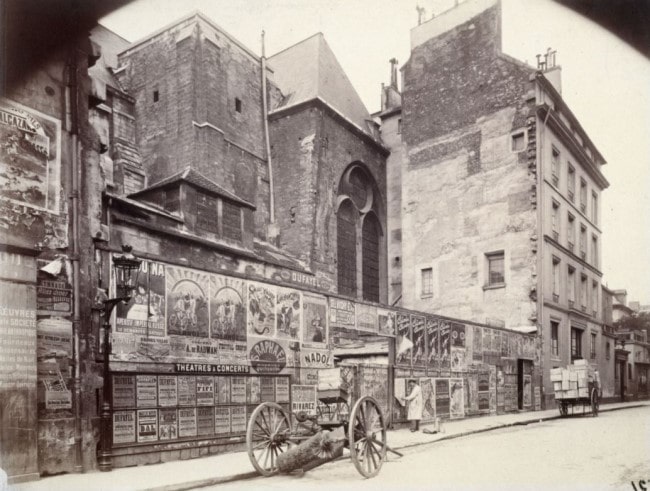

Yet another new perception of urban reality was the idea of people as spectators of pastimes or spectacular events. The Paris of the 19th century was filled with street musicians, strongmen, acrobats, jugglers, bands in parks, early aeronauts and more. That’s not to mention the “unintended” spectacles like fires, political violence, and natural disasters. This resulted in a sort of “meta-artwork” of images within images, decades before postmodernists like Warhol and Rauschenberg.

Camille Pissarro, La place du Théâtre Français (C) Musée d’Orsay

During this period of exploitation of the poor, women became objectified as sexual fetishes like never before. As sexual mores loosened, voyeurism was increasingly found in public entertainment and the arts. Some of the early cinema was devoted to peephole views of women in various states of undress. What seem quaintly lubricious on one level are also fascinating views (we’re like Peeping Toms ourselves as we watch the pervy old clips) of the male gaze in action.

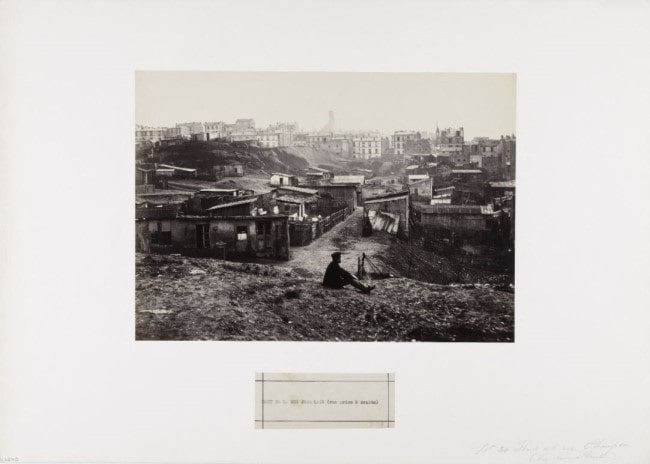

Charles Marville, rue Champlain (C) Musée d’Orsay

In addition to the manmade world of the city, the 19th century was also a time of new scientific views of nature. As the scientists studied both the micro and macro dimensions of nature, the arts followed. Painters like Claude Monet expressed the effect of light (or the lack of it) on perception, while illustrators gave precise renditions of birds, animals and plants. The cinema weighed in, including startling views of microscopic life.

Fillette au chevet d’une jeune femme (C) Musée d’Orsay

The 19th century was also when the French Empire rivaled that of the British, stretching from the Americas to Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. While this led to exploitation and abuses, it also made the French curious about the looks and ways of exotic lands. There were many intrepid explorers, missionaries, soldiers, writers and capitalists who ventured far and wide, and at the turn of the century they started to take movie cameras with them. Among the evocative images on view is a caravan out of the Arabian Nights, but granularly real, making its way through the desert.

Constant Puyo, Balcon a Montmartre (C) Musée d’Orsay

All the rapid changes that came about at the end of the 19th century — scientific, cultural, political, industrial, and technological — pushed people to see in entirely new ways. The traditional arts led the way in depicting these changes (and themselves became innovative and experimental) but the young medium of cinema recreated them as the older media could not. Something radically new was happening, and Paris was its epicenter.

“Enfin le Cinéma” continues until January 16, 2022. The Musée d’Orsay is open every day except Monday from 9:30 am until 6 pm (except for Thursday, until 9:45 pm). The normal price is 16 euros (see the museum’s site for reduced and free fare).

1 Rue de la Légion d’Honneur, 7th arrondissement

Lead photo credit : Enfin le cinema! (C) Musée d'Orsay

More in Art, cinema, film, Musee d'orsay, theater