Flâneries in Paris: Explore the Hôtel de Ville

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

This is the 39th in a series of walking tours highlighting the sites and stories of diverse districts of Paris.

It’s so easy to forget that the square outside the Hôtel de Ville, where Parisians gather to watch sporting events on a giant screen or glide over the outdoor ice rink each winter, is the hub from which the City of Paris has been governed since 1357. It’s an area I’ve never thoroughly explored, so I decided to take a look around the Place de l’Hôtel de Ville and do a little circuit of the building from which Mayor Anne Hidalgo sends out her thoughts on running – and greening – the city.

Her influence was immediately apparent, in that on the day I visited much of the square was fenced off, accessible only to the workers busy creating the city’s third “urban forest.” Fifty large trees and 20,000 plants were being dug in to create a forest atmosphere in this most metropolitan of spaces, a project which just opened to the public on June 21st. The Place de l’Hôtel de Ville is freighted with history, perhaps more than any other spot in Paris, but it’s forward-looking too.

La place de Grève and l’hôtel de ville in 1583. Paris à travers les âges, by Hoffbauer, éd. Firmin-Didot 1885. Public domain

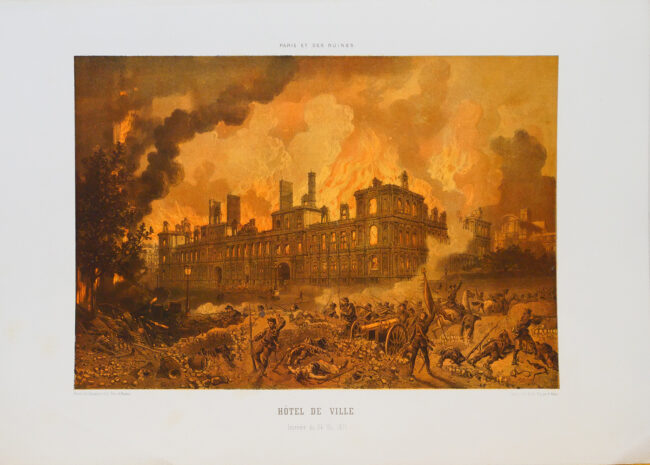

It all began in July 1357 when Étienne Marcel bought a house here as his base for managing the riverside trade nearby. In the 16th century, François I commissioned a splendid new Renaissance building to be his city hall, later expanded and embellished by other kings. When the Third Republic was declared in 1870, the new National Committee moved in, although not for long because soon the revolutionary Communards set fire to the whole building, destroying it and centuries of archives almost completely. By this time, the square’s colorful past – think revolutions, grizzly public executions and some of the most famous speeches from France’s history – meant that losing the Hôtel de Ville was unthinkable. So, rebuilding began almost immediately.

L’Hôtel de Ville burned on the 24 May 1871 by the Communards. Public domain

The façade in front of me was very much modeled on François I’s flamboyant Renaissance style, for example in the statues of artists, scientists and politicians by 230 different sculptors which adorn the building. The city’s coat of arms is prominently displayed, bien sûr, and imposing statues representing Art and Science flank the ceremonial doors. It’s a celebration in stone of French culture and on the day I visited, in the autumn of 2024, civic pride was further boosted because the façade was still festooned with banners celebrating the great success of the recent Paris Olympics.

I found it all very splendid but could not forget that for some 500 years bloodthirsty crowds gathered here to watch executions. The cruelest punishments were reserved for those who’d harmed royalty, such as François Ravaillac who ambushed Henri IV, then stabbed him to death. The assassin was publicly tortured here in May 1610 before being hanged, drawn and quartered. It was here too that the notorious guillotine was first used and it’s said that when the first victim, the robber Nicolas Pelletier, was decapitated on April 25th, 1792, members of the crowd who had gathered to watch complained that it was all too quick and not at all the spectacle they’d been anticipating. I wondered whether today’s skaters and concert-goers recall this grim history.

Ancient staircase at the Hôtel de ville. Charles Marville. Public domain

I knew too that some of France’s most epoch-changing moments had happened right here: Louis XVI making a speech wearing a red, white and blue cockade to try and show some allegiance with the people; the revolutionaries he’d addressed taking over the Hôtel de Ville as their HQ soon afterwards; cheering crowds welcoming the new, more liberal, monarch Louis-Philippe in 1830; the declaration of the Second Republic which ended his reign just 18 years later; the draping of the whole building in imperial colors a mere four years after that as Napoleon III staged his coup d’état.

Etienne Marcel statue. Photo: Marian Jones

More recently, it was here that the Liberation of Paris really began. I spotted a marble plaque, inscribed in gold lettering, marking the award of the Croix de la Libération to the City of Paris by General de Gaulle himself, citing the city’s “unshakeable resolution” and the “glorious battles” which broke out in central Paris on August 19th, 1944 as the city broke free of German occupation. Who is not moved when recalling de Gaulle’s triumphant speech here at the Hôtel de Ville on August 24th, declaring that his beloved, battle-scarred Paris had been wrested back from the Germans at last? “Paris, Paris outraged! Paris broken! Paris martyred! But Paris liberated!”

View of Ile de la Cite. Photo: Marian Jones

The Place de l’Hôtel de Ville is also known as the Esplanade de la Libération because it was here that Général Leclerc’s troops fired their first shots at German troops. A sign on the entrance to the little park at the riverside end of the square, the Jardin des Combattants de la Nueve, explained more. The 9th Company, led through the Porte d’Italie and on to the Hôtel de Ville by General Leclerc, were known by the Spanish word for nine, nueve, because many of them were Spanish Republicans who’d fled Franco’s dictatorship. They were, said the sign, Héros de la Libération de Paris.

Nueve plaque. Photo: Marian Jones

Just around the corner was lots more history! A “brown oar” plaque explained that the square was a popular site for celebrating the summer solstice in earlier centuries, when noisy revelry involving royalty, jubilant crowds, fireworks and a bonfire would last all night long. A glance up showed me the imposing statue of Étienne Marcel astride his horse surveying the riverbank where he had once been the most important citizen in Paris. As Prévot des Marchands, a 14th-century forerunner of the mayor, he had gained popularity for winning concessions from the king and for leading a revolt against the nobility. Unfortunately, he then fell from grace, assassinated because he was deemed to have become too powerful. But a nearby metro station on Line 4 is named in his honor.

View of the Conciergerie. Photo: Marian Jones

I crossed the busy Quai de l’Hôtel de Ville to enjoy fine views along the Seine of the streets of the Ile de la Cité framed by overhanging trees and of the turreted towers of the Conciergerie. This little riverside spot was once known as la grève, meaning “shore” and served as the main port in Paris, a busy place where merchants unloaded hay and wheat, wine, wood and coal, prospering themselves and the city. That’s why the square was originally called Place de la Grève and why, because the boatmen sometimes downed oars in a bid for better terms, the word grève has come to mean “strike.”

View of Ile de la Cite. Photo: Marian Jones

Along the Rue Lobau, running along the back of the Hôtel de Ville, a side street led up to the Church of Saint-Gervais, a scene of tragedy in 1918 when a German bomb fell during a Good Friday service and over 80 people were killed. The Place St Gervais in front of it is being transformed into a memorial garden for a more recent atrocity, the night of November 13th, 2015 when Islamist terrorists killed 130 people in attacks on the Bataclan concert hall and other sites. Yet again, I am reminded of the respect Paris shows to the past, whether to recall distant glories or in memory of those who have been wronged.

And rounding the last corner back to the Rue de Rivoli, I found another of those things which the City of Paris does so well. The railings alongside this side of the Hôtel de Ville are often used as a temporary gallery, a place to hang artwork where passing shoppers and businessmen going about their day will see it. This time, it was a selection of black and white pictures, taken by the Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer David Turnley. He has traveled the world for 50 years, documenting wars and natural catastrophes, but his base is Paris and these 30 photographs are a testament to his love for his adopted city.

I’d spent this walk recalling momentous events from the city’s past, pieced together from my reading of history books. Each of David Turnley’s pictures captured a moment from the past too, not so very long ago, yet nostalgically fixed in black and white: a child rushing through the Jardin du Luxembourg with a little toy sailing boat, lovers kissing on a bridge somewhere nondescript, yet recognizably Parisian, workmen pausing for an instant, halfway up the Eiffel Tower. It all came together in my mind, reminding me that this really is the most captivating of cities.

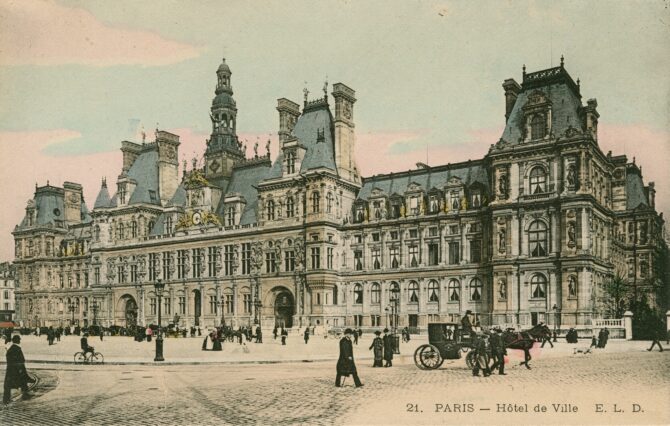

Lead photo credit : vintage postcard of Hotel de Ville de Paris, 19th century. Department of Image Collections, National Gallery of Art Library. Public domain

More in Flâneries in Paris, Hotel de Ville, urban forest