The 80th Anniversary of the Liberation of Paris

The Olympic Games are over. The Paralympics have begun. Between the two, Paris celebrated a highly significant anniversary: August 25th marked 80 years since the city was liberated from Nazi occupation, ending the period still known as les années noires, the “dark years.” So now is a good time to put the spotlight on a museum in the 14th arrondissement which not only tells the story of the occupation and its dramatic ending, but is situated exactly where some of the main events unfolded.

For the Musée de la Libération de Paris is directly above the underground network of bunkers chosen as the secret HQ of Colonel Henri Rol-Tanguy, regional commander of the FFI (French Forces of the Interior). Their efforts, as allied troops approached to liberate Paris, led to the surrender of General von Choltitz, the German Military Governor of Paris. In the museum itself the story is explained through documents, realia and film footage and you can also tour the hidden network of tunnels and rooms from which, as a plaque explains, “were given the orders for the victorious Parisian insurrection of 19th – 25th August by the Parisian Liberation Committee and the National Resistance Council.”

courtesy of Musée de la Libération de Paris

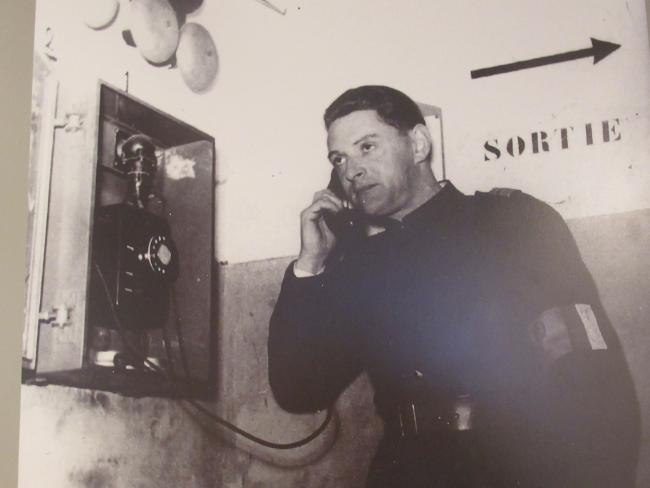

In August 1944, Colonel Rol-Tanguy urgently needed a city-center hideout to use as his headquarters and he chose an air raid shelter 26 meters underground at the Place Denfert-Rochereau. It could be reached by subterranean tunnels and already had ventilation and a phone network linking it to other air raid shelters and to the Préfecture de Police, which – crucially – bypassed the official telephone network and so would not be tapped by the Germans. Almost unbelievably, the Germans knew of its existence and made a daily phone call to check that “all was calm in the shelter,” unaware that for the crucial period of August 20th – 28th, it was the nerve center of the unrest which contributed so much to the liberation of the city.

Down in the maze of concrete corridors and little rooms you can easily imagine it as a clandestine command center. In one small room, five women, led by Colonel Rol-Tanguy’s wife Cécile, codenamed “Lucie,” worked around the clock, operating the telephone system, receiving information and relaying orders. Colonel Rol-Tanguy himself later wrote that this operation, so swiftly set up and disbanded after a week was “one of the essential means of conducting the battle for Paris. While I was circulating with my bodyguard to coordinate the overall action, my general staff could follow the development of the fighting closely, deploy the Free Corps at one point or another and surprise the Germans.”

Crowds of Parisians celebrating the entry of Allied troops into Paris scatter for cover as a sniper fires from a building on the place de La Concorde. August 26, 1944. Verna (Army). Public domain

As American and other allied troops approached Paris from the Normandy coast, liberating towns and villages on their way, civil unrest was growing in Paris and threatening the German occupation from the inside. On August 15th, the Paris police went on strike and in the days which followed so did post and telecommunications workers, then metro and railway staff until eventually a general strike was called. Colonel Rol-Tanguy also organized the setting up of barricades to further disrupt movement around the city. On August 19th, hundreds of policemen marched on the Préfecture de Police, securing it and raising the tricolore, the first time it had flown from a public building in Paris since the occupation of the city had begun 1500 days earlier.

Fierce battles were fought as the Germans tried to regain control. Colonel Rol-Tanguy sent the Americans an urgent request for more arms and ammunition. Help was indeed coming and early on August 24th General Leclerc’s 2nd French Armoured Division was so close that he dispatched a little Piper Cub aeroplane to fly over Paris and drop the message “Tenez bon. Nous arrivons’.” (“Hold on. We’re Coming.”) On August 25th, fittingly the Feast Day of St Louis, Patron Saint of France, the liberation became a reality. General Choltitz signed a surrender document, the last SS garrison left their station at the Palais de Luxembourg at 7:35 pm and jubilant crowds gathered at the Hôtel de Ville to sing the Marseillaise.

Colonel Rol-Tanguy in the bunker, as pictured at the Musée de la Libération – Leclerc Moulin.

The museum’s chronological display begins with an introduction to two key figures, the national Resistance leader, Jean Moulin and the aristocrat, Philippe de Hautclocque, known as Général Leclerc, who, alongside American troops, led the 2nd French Armoured Division into the city on the morning of August 25th. The next section, The Defeat and the Moment of Choice, explains the devasting events of June 1940 as German troops arrived in Paris and much of the population fled to the country even as Général de Gaulle was making his radio appeal over the BBC from London for the French to continue the fight: “The flame of the French resistance must not be extinguished.”

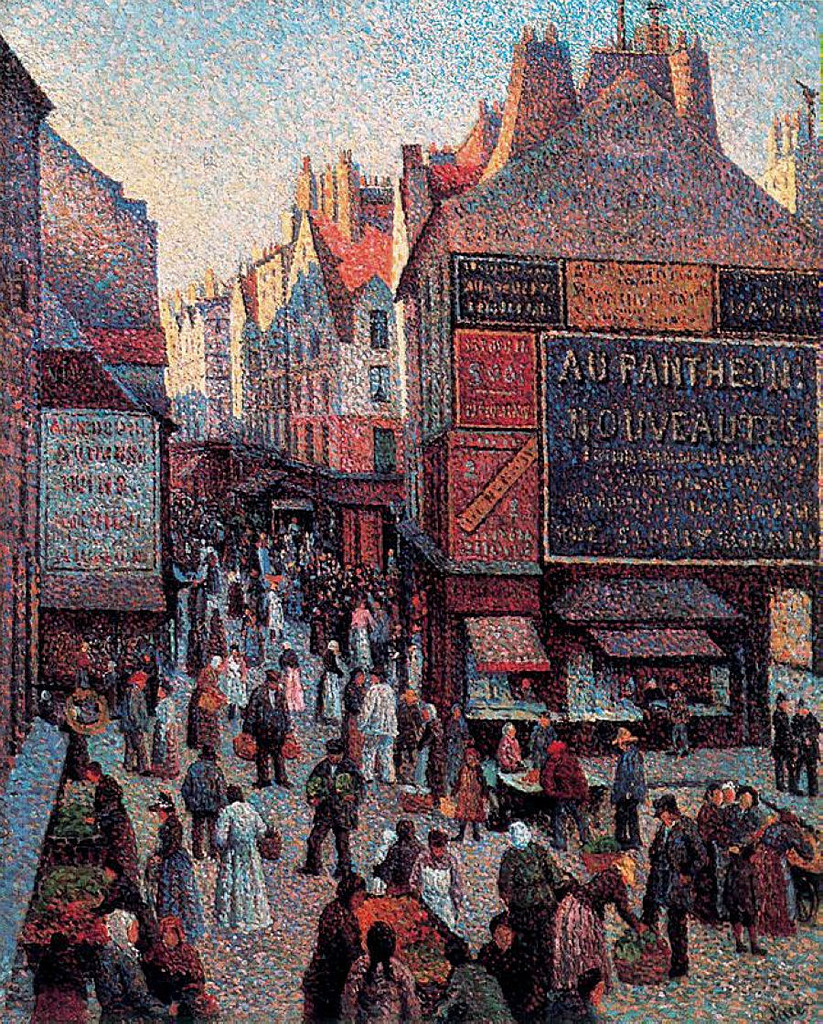

Exhibits in the section on Occupied Paris recall the reality of life for those who remained in Paris. Ration cards are on display, alongside photos of Parisians foraging desperately for potato peelings and a diary account of trying to shop on the Rue Mouffetard and finding the stalls largely empty. There is also evidence of some of the many ways in which Parisians tried to resist: issues of Défense de la France, one of the first Résistance newspapers and a forger’s kit containing the blank documents and phoney City Hall stamp from which false papers were produced for Resistance members.

La Rue Mouffetard, Maximilien Luce (French, 1858-1941). Indianapolis Museum of Art. Public domain.

Jean Moulin’s wartime role as the unifying force of the French Resistance is told through items such as the false ID card with which he travelled to meet Général de Gaulle in London, a coding table he devised for sending secret messages and posters for exhibitions at the art gallery in Nice he ran as a cover for his resistance activities. Here too is the last letter he wrote to his mother and sister before his arrest in June 1943. After torture by the Gestapo, he died during transit to Germany on July 8th, 1943. Material relating to Général Leclerc includes photographs of him arriving in Normandy in preparation for the liberation and in Paris alongside Général de Gaulle after its successful conclusion.

Jean Moulin in 1937. © Wiki commons

Exhibits relating to the liberation of the city include posters of the mobilization order signed by Colonel Rol-Tanguy on August 18th, alongside photographs of Parisians erecting street barriers from paving stones and sandbags to prevent German vehicles from circulating. A set of instructions for making a molotov cocktail and FFI requisition orders demanding the use of certain key buildings give an idea of a city where the hoped-for ending of a long nightmare began to seem possible.

The joyous days after the liberation are celebrated in film footage, showing jubilant crowds thronging the streets and still photos of key moments such as Général de Gaulle, framed by the Arc de Triomphe behind him, marching in triumph down the Champs Élysées with his generals, resistance leaders and members of the government. Also on display is an essay written by 9-year-old Ginette Masson describing the arrival of Général Leclerc and the 2nd Armoured Division into southern Paris. On the back she has drawn French, American, British and Soviet flags alongside vases of flowers in patriotic red, white and blue.

General de Gaulle and his entourage proudly stroll down the Champs Élysées to Notre Dame Cathedral for a Te Deum ceremony following the city’s liberation on 25 August 1944. Unknown author. Public domain.

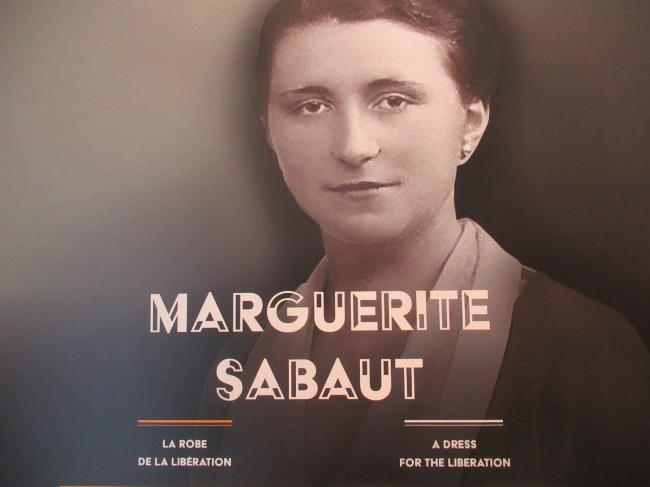

A highly memorable exhibit is the patriotic dress hurriedly sewn by Marguerite Sabaut to wear out in the streets as she celebrated the liberation. The French flag and the wearing of anything red, white and blue had been forbidden throughout the occupation, but Marguerite gave her white cotton dress bold red and blue stripes at the hem and on the sleeves and sewed on drawings of Paris monuments – the Arc de Triomphe, the Eiffel Tower. The resulting dress perfectly captures the heady atmosphere of Paris as the longed-for liberation became a reality.

The museum also runs temporary exhibitions, such as this summer’s Sportifs Résistants, highlighting 20 sportsmen and women, now largely forgotten, who joined the Resistance. Some, such as Jeanne Matthey, survived. Four times French Tennis Champion, she served as a nurse in World War I and joined the Resistance in 1940, for which she was tortured and deported. Many others gave their lives for the cause. Former French high jump champion, Camille Lecinché, who carried out sabotage missions in the Auvergne, was only 22 when his unconscious body was seen being loaded into an SS van in Vichy. He was never seen again. Athletics champion Charles Berty produced clandestine materials in his Grenoble shop, but was denounced and died at Mauthausen concentration camp in April 1944, aged 32.

The Musée de la Libération is of special significance on this 80th anniversary. Until now it has been possible to hear the stories it has to tell at first hand, but today the number of those who witnessed these events is dwindling and that makes it even more important that the museum is there to recount the history. Anne Hidalgo, mayor of Paris, expressed this eloquently when she wrote the foreword to the museum’s guidebook: “At a time when the last witnesses to the Second World War are inevitably being silenced, we have a collective responsibility to preserve and develop their heritage and pass it on to future generations.” If you have not been to the Musée de la Libération, do pop in next time you are near the Place Denfert-Rochereau.

DETAILS

Musée de la Libération

4, Avenue du Colonel Henri Rol-Tanguy, 14th arrondissement

Nearest metro station Denfert-Rochereau

Open Tuesday – Sunday, 10 am – 6 pm

Entry free

Lead photo credit : Crowds of French patriots line the Champs Elysees to view Free French tanks and half tracks of General Leclerc's 2nd Armored Division passes through the Arc du Triomphe, after Paris was liberated on August 26, 1944. Public domain

More in Liberation, Liberation of Paris, Museum, World War, WWII