Henri IV’s Legacy in Paris

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

The world will be reminded of Henri IV this summer when, during the opening ceremony for the Olympics, TV cameras will follow the athletes down the Seine and under the Pont Neuf. The statue of France’s first Bourbon king, who reigned from 1589 to 1610, sits astride his horse on the beautiful bridge which he commissioned, and gazes downriver in the city where he had to fight hard to gain acceptance, but where he eventually became France’s best-loved monarch. So, who was he and where can you “find” him in Paris today?

View of the Pont-Neuf bridge in Paris. Photo credit: Sumit Surai/ Wikimedia Commons

When Henri was born in 1553, no one thought he would ever be king of France. Catherine de Medici, wife of Henri II, had already borne three sons and a fourth would follow. Indeed, although one died, the other three went on to reign, while Henri’s destiny was to become king of Navarre, which he did in 1572. This was also the year of his wedding to Marguerite, daughter of the deceased Henri II. It was a political match, an attempt to ease religious unrest by admitting a Protestant into royal circles, deemed safe enough at a time when the Catholic succession looked secure, through Charles IX, his younger brother Henri and – it was hoped – their future heirs. But the wedding was disastrous, unleashing such terrible bloodshed that it became known as “the scarlet nuptials.”

Portrait of Catherine de Medici and her children. Horace Walpole’s Strawberry Hill Collection, Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University/Wikimedia Commons

Many Protestants had gathered in Paris for the ceremony at Notre Dame on August 18th, 1572 and the week of celebratory balls and suppers which followed. But on August 25th, in what became known as the Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, an estimated 3,000 Protestants were brutally slaughtered. It began in the Louvre Palace, where the bridegroom Henri and his Protestant nobles were staying. Desmond Seward, Henri’s biographer, writes: “The Louvre’s chambers, withdrawing rooms and antechambers all dripped with blood and were littered with dead or dying Protestant lords.” Henri was spared, being a “Prince of the Blood,” but a mob outside spread violence through the city and many more were murdered.

Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre. Painting by François Dubois, a Huguenot painter who fled France after the massacre. Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts/ Wikimedia Commons

This fueled more conflict between the two religions. But in 1589, when Henri III, fourth son of Henri II, died, a string of royal deaths coupled with a lack of royal children saw him name Henri de Navarre as his heir. Would the Catholic hierarchy accept a Protestant king? It seemed not, for fighting continued. However, four years later, Henri made a pragmatic move. He converted to Catholicism in a ceremony at the Basilica of St Denis and although some reported he had given a cynical reason, namely the idea that “Paris is worth a mass,” it did render many of his Catholic opponents less hostile.

Henri III on his deathbed designating Henri de Navarre as his successor. 16th century tapestry. Public domain.

A few months later his official coronation took place at Chartres Cathedral. Henri then managed to end the religious strife which had divided France for 40 years by issuing the Edict of Nantes in 1598. It confirmed Catholicism as the state religion, but granted a measure of freedom to Protestants. Henri could now focus on taking France forward and so began the achievements for which he is remembered: bringing prosperity to France, by boosting agriculture and manufacturing – including introducing the silk industry from Italy – and overseeing a building program of roads, canals and some landmark projects in Paris which are still there for us to admire today.

The Grande Galerie during the Louvre’s early years. Hubert Robert/Wikimedia Commons

As early as 1595, Henri commissioned the Grande Galérie du Louvre, a new wing linking the Louvre Palace with the Tuileries Palace, a beautiful building along the right bank of the Seine which was opened in 1607. Its length – 460 meters – stunned everyone and was an early sign that the flamboyant Henri thought big. The gallery is still part of the Louvre today, albeit shorter than the original because it was remodeled under Napoleon III in the 1860s.

Portrait of Marie de Médicis by Frans Pourbus the Younger. Wikimedia Commons

There are more reminders of Henri in the Louvre collection, where you can see a magnificent portrait of him in armor, painted in the early 1600s by Frans Pourbus and also pictures of two of the women in his life. The Galerie Medici (currently closed, due to reopen this summer) contains a series of 21 paintings of Marie de Medici, Henri’s second wife and the mother of his heir. And the portrait of Gabrielle d’Estrées and One of her Sisters by an unknown artist shows his favorite mistress, mother of three of his children, who died in 1599 giving birth to a fourth.

Gabrielle d’Estrées et une de ses sœurs. Fontainebleau School. Public domain

Perhaps the most stunning of Henri’s legacies in Paris is the Place des Vosges, commissioned by him in 1605, but completed only in 1612, two years after his death. It was originally known as the Place Royale to emphasize its royal connection and it is an example of Henri’s entrepreneurial flair, for it was designed as a base for the silk market he hoped French manufacturers develop to rival for those in Lyon and Milan. Some buildings were to be used for manufacturing and the merchants could use the arcades to showcase and sell their wares.

Place des Vosges. Photo credit: Marko Maras/ Flickr

The exquisite beauty of the Places des Vosges is a testament to Henri’s excellent taste. It was one of the first “perfect” squares in Europe, that is its four sides are equal in length, and the sense of harmony is increased by the uniformity of the buildings – red brick facades, decorative stonework patterns, vaulted arcades at ground level and steep blue slate roofs with dormer windows. The central garden is another perfect square with symmetrical paths leading to a fountain centerpiece. It was – is – perfection in city-planning.

Aerial view of Place des Vosges, in Paris, from the south, looking north. Photo: Des Racines et des Ailes/Wikimedia Commons

Henri also commissioned the beautiful Pont Neuf and took a great personal interest in its construction, visiting regularly to inspect the progress and delighting the builders by joking with them. The bridge’s 12 elegant arches, decorated with mascarons, or grotesque faces, make it one of the highlights of a river trip and the statue of Henri sitting on horseback and looking down the river is a Paris landmark. It was commissioned by his wife, Marie de Medici, in the early 1600s, but not finished until 1614, several years after he had been assassinated. Along with other royal statues, it was torn down during the revolution, but rebuilt in the 19th century.

Pont Neuf bridge. Photo credit: Steve/ Wikimedia commons

A plaque in Rue de la Ferronerie, just a few minutes’ walk from the Pont Neuf, reads: “This is the spot where King Henry IV was assassinated by Ravaillac on 14th May, 1610.” Popular though he undoubtedly was, Henri had already survived a number of assassination attempts, but the fanatical Catholic, François Ravaillac, had made careful plans. He followed the king’s carriage from the Louvre and, when it entered the narrow Rue de la Ferronerie and was held up by other coaches, he leapt up, leaned into the open carriage and stabbed Henri. The king cried out “I am wounded,” before being stabbed again and falling back dead.

Assassination of Henry IV, engraving. Gaspar Bouttats/Wikimedia Commons

Two further places connected to Henri IV are the Musée Grévin where there is a life-size tableau of the murder scene, and the Basilique St Denis where his tomb is. The Square du Vert Galant right on the tip of the Île de la Cité is named in his memory and refers to the larger-than-life quality for which his subjects loved him. “Vert Galant” refers to a lively man with a love of women and it neatly sums up his legendary ability to grab life with both hands and enjoy food, wine, raucous gatherings and, most of all, female company.

The Square du Vert Galant, seen from the quai de Conti. Photo credit: Mbzt / Wikimedia commons

Henri is known to have had at least 50 mistresses. His favorite, Gabrielle d’Estrées, bore him three children, and he had more with at least three other mistresses. He is said to have loved them all and to have been a very fond father, one who, as Desmond Seward wrote, “rejoiced at the birth of each new child, whoever its mother.” Henri’s second wife, Marie de Medici, bore him six children, including the future Louis XIII, so the succession was secure and his string of lovers and illegitimate offspring was accepted by most as an example of his determination to enjoy excess in all life’s pleasures.

History remembers Henri IV as the king who stabilized France after decades of religious fighting and restored economic stability to his almost bankrupt country. Today’s visitors to Paris can enjoy the glorious buildings he left behind – the Grande Galérie du Louvre, the Place des Vosges and the Pont Neuf. His subjects loved him as a king who understood their desires and promised that under his rule every laborer should enjoy a “chicken in the pot” on Sundays. Perhaps it was Henri himself who best summed up his many achievements when he said, “I make war, I make love and I build.” No wonder then, that he is fondly remembered as “le bon roi Henri,” Good King Henri.

Statue of Henry IV on the Pont Neuf (1618, destroyed 1792, replaced 1818). Photo credit: Mbzt/ Wikimedia Commons

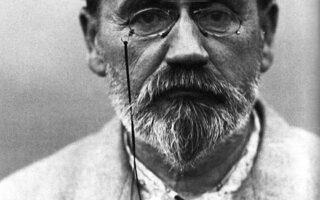

Lead photo credit : Henri IV, King of France. Royal Collection/Wikimedia Commons

More in Henry IV, history, King, Royals