La Première Fois: A Paris Memory by Kathleen Burke Comstock

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Kathleen Burke Comstock in February 1973 at the Sorbonne

The Bonjour Paris editorial team recently requested reader submissions with memories from first trips to Paris. We were overwhelmed with wonderful responses, which we are publishing in a special series. (Read other installments here.) Below, writer Kathleen Burke Comstock paints a vivid portrait of Paris in the 1970s.

1973 Orly international airport. At the taxi stand, I watched in horror as a man urinated behind a barrier. He was using what I was to discover was a commonplace receptacle in France, the pissoir. An invention of the 19th century, the pissoir claimed real estate on many of Paris’s grand boulevards, aiding and abetting men who otherwise would have gone into a street gutter or against buildings. The man promptly finished his business, slid out from behind the pissoir and zipped up as I– too late– tried to avoid his indolent stare. My teen American self was not prepared for this type of Parisian welcome. There would be more to come and as it turned out, many city accoutrements like the pissoir would in the not too distant future, become obsolete. Orly airport itself was soon to be a backup international airport to the newer Roissy Charles-de-Gaulle, changing forever the way Parisians and tourists alike would arrive at and depart from the City of Light.

Bleary eyed from first-time jet lag, I had one thing on my mind, to get to where we were going and sleep. But my host Eddie had other plans. First we would sample his favorite café in the Latin Quarter near the Sorbonne, where Eddie and my friend’s sister Anita were studying medicine. They had secured me and my high school roommate a guest room at the university. It was February and very cold. I could not stop shivering. It seemed heat was a privilege offered in short bursts from rarely-sighted hissing radiators or not at all in the drafty halls of this age-old institution. So, in hindsight the café was a good second option to soothing a weary frozen body.

At the café, we cuddled up against one another, rubbed cold hands, and chatted about the voyage. Black and white penguin-looking waiters glided and shimmied about the crowded café, eventually delivering to our table petit cups of espresso and for me an oversized mug of the most delicious hot chocolate I ever tasted. My time change clock had not yet adjusted, so I also requested a yogurt, delivered in the tiniest container (4 oz) I had ever seen. It was the first of many times my stomach growled in disappointment as I tried to tame an appetite never quite satisfied with this ‘small is better’ style of dining.

When it was time to make a phone call to connect with my roommate, I was told I would need a jeton. Reading the puzzlement on my face, Eddie laughed and proceeded to usher me towards the bar where he handed over some francs for a silver coin, the jeton. We descended a winding staircase to the lower level where more pissoir type setups stood in plain view for the men, and a ripe-smelling and leaking toilet room was available for the ladies. I inserted the jeton and Eddie dialed. Jetons would be used for further phone communication as well, whether in a post office, café or public booth. In Paris, it was the intermediary between you and your interlocutor.

We next donned coats and hats, headed towards the nearest bus stop and waited in line as an agent punched little white tickets that Eddie handed over. In the crowded space, we were pushed along to the back of the bus. It was a platform bus, with a rear standing-room only section open to the outside and that raw biting cold. The hop-on hop-off idea circa 1973.

“Now you can see all of the city as we go!” Eddie cried with delight. The hot chocolate’s success in warming my hands and feet quickly dissipated in the wind-blown chill of the swiftly moving bus. Teeth chattering, I offered a polite nod and prayed that wherever we were it wasn’t far from the Sorbonne. That evening Paris was so cloaked in winter’s widespread, indecipherable, and dark mantel that I could neither analyze nor appreciate the city’s beauty. All around, the French chattered in a Parisian clip that simply did not translate to my eager and alert ears. So much for four years of high school French.

And then there was la lettre pneumatique, another communication tool integral to daily life in Paris. One could place a letter in a cylindrical container that would be inserted into a city-wide sub system of pressurizing duct work that would accept the tubes, or navettes cylandriques, and direct them to one of many terminal destinations. In the span of an hour or so, the communication was delivered. Often used for government and business purposes, local color also had it as the means whereby the French conducted their mid-day amorous rendez-vous. I never used a pneumatique, but its convenience and popularity had been at an apogee through the mid-20th century and even beyond.

Back then no Parisian woman in her right mind stepped out of her home in jeans, or in other than her highest best heels. Heels on which they managed to traverse a city cobbled in stonework replete with crevices and cracks. That these women managed to expertly navigate these stumbling blocks is a testament to the ever French prioritization of appearance and la mode. The hair style of the day was a layered look of dark roots and bleach blonde strands. The preferred coat a jacket of faux fur in bright pink, royal blue or Big-Bird yellow. Oh, yes, and a cigarette usually angling from red rouge lips. The exception seemed to be elderly women who were stooped and wore black.

Tiny cars zipped about the city with vengeance. You had to watch where you were going because, at speeds that conjured the Grand Prix, drivers with priority would enter a major road from the right. For pedestrians and drivers alike la priorité à droite was a code adhered to without fail or fault. Lack of attention on the part of the neophyte or foreigner meant paying a dear price.

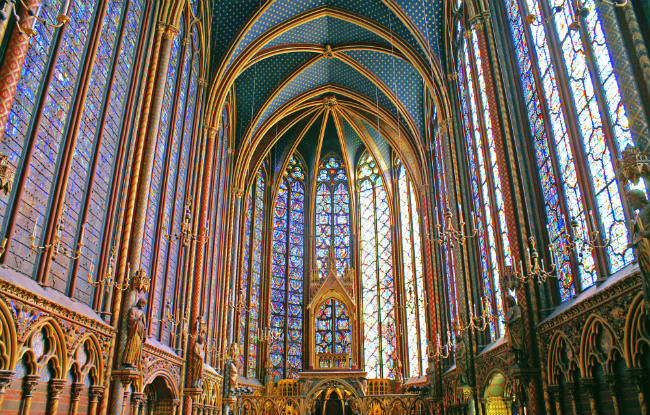

But then there were the monuments and the museums, the fresh daily bread that made headlines all on its own when its price increased, the cafés to sit in endlessly, the Eiffel Tower viewed from both incongruous unexpected side streets as well as from the magnificence of the Trocadéro. The Sainte Chapelle, where Eddie took me one day when we both had free time and others in our entourage were otherwise occupied. Once at the second floor we settled in a corner and gazed upwards at the seemingly endless vertical arrays of colored stained glass. He confided to me he came to the chapel to ease his tensions from study, his fears of the future, his jumpy mind. Because here was as “close to heaven as you can get on earth. Here in Paris.”

Eddie’s love of Paris was contagious for me. He and Anita married and moved to the States to practice medicine in California while I took work in Paris and eventually settled in the city. In time my husband and I purchased an apartment in a quiet residential neighborhood of the 17th arrondissement. I mastered the Parisian clip that cannot compare with other regional styles of spoken French. I learned to navigate bus system and Métro, growing territorial for a certain back seat on the number 66 bus, my corner seat by the radiator at the local café, the heft and charm of the city as it flares up at rush hour and settles down in the wee hours. My days of frozen school girl surprise and awe are a memory that grows increasingly dear with the years.

There are no more jetons, pissoirs, or pneumatiques. The buses, thankfully, have been rebuilt to exclude open air construction. Women sport sensible flat footwear and jeans of all possible ilk. The spikey bird look of the 1970s is an amusing footnote to an era fast fading into the collective consciousness. Nonetheless a Parisian will still think hard about exiting her home without makeup or her favorite coordinating scarf. Simply put, Coco Chanel’s mantra holds firm in the heart of this city’s women:

Personne n’est assez fort pour être plus fort que la mode. (No one is stronger than la mode.)

When one experiences the genuine day-to-day of Paris, it becomes organic like any other place—joys, woes, obligation, decisions, options, longing, emoting, sharing. And yet, St. Chapelle is the first place I take visitors, so they can experience that heaven on earth feeling that years ago so moved Eddie and, by association, me. The tiny yogurt containers have made their way to the States, and so have tiny cars while priority from the right is, thankfully, against the law in France. But bread and hot chocolate do not compare, because, while they are offered aplenty in the U. S. you cannot enjoy them the same way –inside a warm Paris café on a chilly February afternoon, watching the green buses woosh by, and the, now less than rail thin, women maneuvering cobbled pavement in stylish sneakers. Cell phones grow from everyone’s ears while jetons and phone cabines are the things of attic memorabilia and antique collections. Pissoirs have been replaced by more generic public toilet booths, and café toilets are still down below but much cleaner. There are many more subway and bus lines and you can get from Roissy to a connecting flight at Orly without ever ascending to street level Paris. Major destinations and intersections remain the same, and so do the station and bus stop names. But they are closer in time.

And with time comes nostalgia for those things that once seemed indispensable and beyond reproach. Technology and cultural mores make our lives more efficient, streamline, and antiseptic too. They pull (or push) us forward. Like people pushed me in 1973, to the rear platform of the bus, to make a phone call with a strange silver coin, to eat smaller portions, to watch out for cars entering on the right. All of it back then banal and of the day to day, replaced in time with other activities and items that arrived on the scene to eventually become themselves what might be called ordinary props to daily life. In an extraordinary place like Paris.

Kathleen Burke Comstock is a writer who spent most of her adult life in France working in the Information Technology business. She has written about her experiences in France for bonjourparis.com and for Traveller’s Tales. A short story about an ornery Paris restauranteur whom she befriended earned a place in the “Best Short Stories of 2005” Traveller’s Tales. She is completing a book about buying an apartment in Paris. She and her husband divide their time between Paris and the Outer Cape Cod of Massachusetts.

Lead photo credit : Kathleen Burke Comstock in February 1973 at the Sorbonne

More in Paris Memory