Zelda Fitzgerald: The Paris Years

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

In May 1924, Zelda, Scott and their daughter Scottie decamped from America to Paris. The extravagance of their lifestyle in the U.S. in the previous four years had left the Fitzgeralds in debt both financially and emotionally. Their hedonistic partying and heavy drinking had left Scott’s writing in limbo and their marriage no longer the fairytale they’d envisioned. Paris was to be a new start for both of them. Scott was to get his writing back on track, and the strong dollar and inexpensive living in France he hoped would alleviate their financial woes.

The Fitzgeralds first contact in Paris was Sara and Gerald Murphy, a fabulously wealthy American couple who owned a majestic house just outside Paris. The Fitzgeralds were immediately invited the next evening and Zelda’s first introduction to the artistic beau monde of Paris, despite being married to Scott for five years and being used to the accolade of the ‘Golden Couple’ in New York, had to have been as impressive as it was unexpected. The guests included amongst others, Cole Porter, Jean Cocteau, Picasso and his then-wife the ballerina Olga Khokhlova. It was through the Murphys that the Fitzgeralds were introduced later to the likes of Miro, Sherwood Anderson, Dos Passos, Ezra Pound and eventually Ernest Hemingway.

For a girl from Alabama, these were heady days indeed. However Paris in the 1920s was not a place to recuperate, to take life seriously, or to stop partying. Paris was not conducive at all to promoting sober, abstemious living which was exactly what both Scott and Zelda so desperately needed.

And it had all started so well such a very few years before.

The publication of Scott Fitzgerald’s first novel, This Side of Paradise, to great critical acclaim in 1920, tipped the balance on Zelda’s decision to marry him. It wasn’t that Zelda did not love Scott madly, but the prospect of marrying a penniless, struggling author had deterred Zelda from accepting Scott’s first proposal.

Zelda Fitgerald, although undoubtedly a Southern Belle, was just as undoubtedly never an archetypal one. There was nothing either demure or coy about her behavior. Feted as a beauty from an early age, Zelda was accustomed to the attentions and avowals of love from the opposite sex and the adoration of her mother, for whom Zelda could do no wrong despite the rumors of her wild and decidedly unladylike escapades.

Zelda was born in Montgomery, Alabama on the 24th of June 1900; her father was a remote and strict man, and as a Justice of the Supreme Court of Alabama, Zelda’s growing reputation for wildness left him coldly disapproving.

With a string of beaus, constant drinking, smoking and partying, Zelda had already shocked Montgomery society. Zelda did not give a hoot. She could not have differed more than Scott Fitzgerald who was never blessed with Zelda’s innate courage and total fearlessness.

Their attraction at country club when Zelda at just 18 was instant and all consuming. Both beautiful and blonde it was hardly surprising they were soon to be known as the ‘Golden couple’.

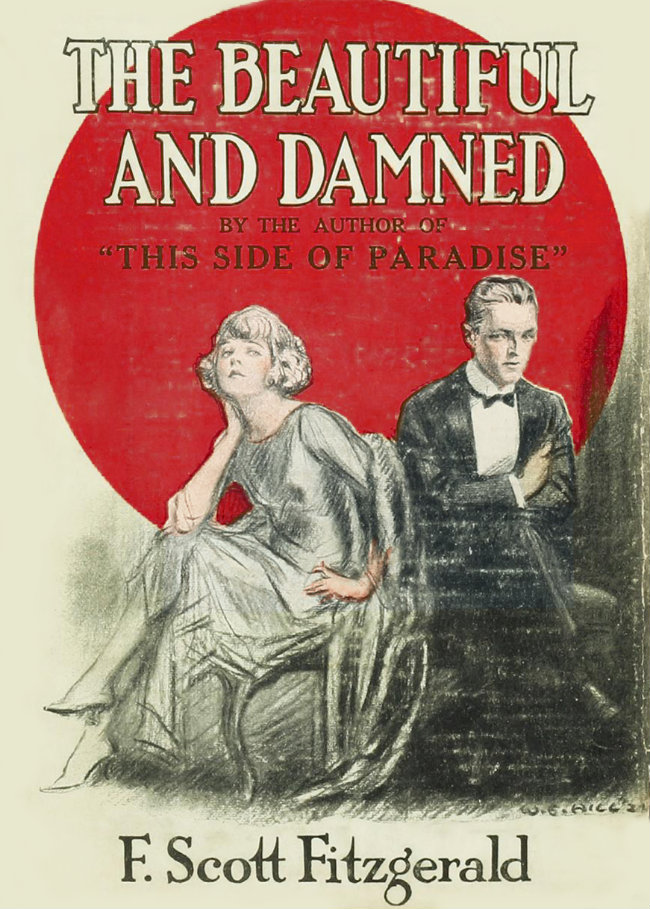

The Beautiful and Damned, first edition

Scott had already published The Beautiful and Damned in 1922 before they came to Paris, but sales had disappointed him. Zelda had recognized herself in the character of the flapper Gloria, and wryly noted similarities in Scott’s novel to her personal letters and diaries. (This was to become a running theme throughout Scott’s work where he used Zelda’s letters and conversations, sometimes verbatim; he felt as her husband and the novelist that they belonged to him.)

The Murphys had already ‘discovered’ the Riviera and were in the process of building a villa in Antibes. They urged the Fitzgeralds to join them and so after a few scant weeks in Paris, Scott and Zelda took the train down to the south of France. In St Raphael they fell in love with the Villa Marie and Scott settled down conscientiously to write every day. Zelda, spending most days on the beach and swimming, soon became bored and her attentions turned to a young French airman, Edouard Jozen. It has never been established how far their affair went– Jozen, who later became Vice Admiral of the French fleet, denied it was anything more than a brief friendship– but Zelda felt she had fallen in love with Jozen and told Scott. Scott was never to forgive or forget her betrayal and Zelda complied with his ultimatum to never see Jozen again.

The first indication of Zelda’s instability came in August that year when a shocked Scott knocked on the Murphys door in the early hours. Zelda had taken an overdose of sleeping pills. No explanations were offered and the matter was never referred to again between the couples.

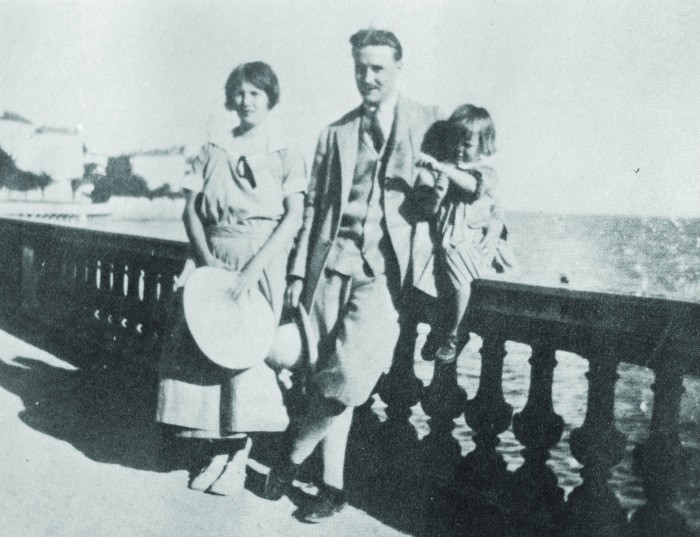

The Fitzgeralds on the Riviera. Photo credit: Collection of John Michel Sordello

It was not until the following spring that the Fitzgeralds returned to Paris, renting a gloomy apartment on 14 Rue de Tilsitt, just off the Champs-Élysées. The heavy furniture was ‘circa grandma’ as Zelda described it, but neither Scott nor Zelda ever showed much interest in any of the apartments they rented in Paris and Zelda was renowned for living in chaotic conditions.

Despite his continued heavy drinking, Scott had finished The Great Gatsby and they embraced the nightlife of Paris with their usual abandon.

Much has been written about Scott’s admiration of Hemingway. He not only admired his writing and his discipline, but was also overwhelming impressed by Hemingway’s macho persona. To Scott, Hemingway was a ‘real man.’ To Zelda, Hemingway was bogus. Their mutual antipathy was to cause more problems in a marriage already unbalanced by Scott’s literary talents and his desire to spend as much time as possible with Hemingway in Paris. In A Moveable Feast, Hemingway‘s dislike of Zelda is apparent. According to him, jealousy of Scott was her motive for encouraging him to stay out all night drinking and partying, leaving him incapable of writing the next day.

And there is no doubt that their partying was legend. From Le Select, the Dingo bar and Les Folies Bobino on the left bank, to bars and cabarets in Montmartre, the Fitzgeralds stayed out until the early hours with little or no bounds to their behavior.

Once more they escaped to Antibes for a month in the summer but dining one evening with the Murphys in St Paul de Vence, Scott had Isadora Duncan pointed out to him at a nearby table. He had drunkenly kneeled before her and Zelda had suddenly leapt off her chair and jumped over the parapet. To the Murphys it was ‘so obviously self destructive and shot through with gratuitous violence’ that their friendship was never to be the same. Zelda had escaped the 200’ drop (landing on a flight of stairs) and re-appeared bloodied but unbowed.

Their sojourn in the south of France had simply demonstrated more problems for the couple while producing no solutions. Their destructive behavior continued, alternatively back in Paris and on the Riviera. Zelda was increasingly ill with colitis and Scott could not stop drinking. Once more their money spent, they left Paris for America.

For a while Scott worked in Hollywood writing film scripts. The money, much needed, was good whether the film script was used or not but he found the work grueling and his flirtation with a young actress only added to Zelda’s unhappiness there. The move to Wilmington was welcome, but the house, all 27 bedrooms of it, was again an unnecessary extravagance with Scott’s heavy drinking once more interfering with his writing.

Zelda Sayre at 19, in dance costume. Public Domain.

Zelda needed something for herself– something that was hers alone. She was a more than proficient writer herself, and had had short stories published, often with Scott’s name attached to them to ‘help sales’. But she knew she could never compete with Scott (in fact he actively discouraged her, since the themes of their novels inevitably had too many similarities). She painted, and for a while, thought this could save her, but ballet was an overwhelming passion, and at the age of 27 began dancing lessons with Catherine Littlefield who had studied under Madame Lubov Egorova in Paris. It was the beginnings of an obsession that would take over Zelda’s life and affect her sanity with disastrous consequences.

In 1928, the Fitzgeralds moved back to Paris, this time renting an apartment at 28, Rue de Vaugirard near the Luxembourg Gardens.

Zelda was introduced to Madame Egrova and began ballet lessons with her three times a week. The lessons, eight hours a day, would have been arduous for a much younger woman; for Zelda they were as all consuming as they were exhausting. She no longer wanted to party every night and Scott, resenting her obsession and lack of attention to him, continued his nights out with his drinking partners. They were quarreling more and more, and when they weren’t, Zelda appeared to be in a world of own. Their marriage was turning brittle with resentments and old grievances. Zelda, although reliant on Scott financially, did not want to play the obedient, docile wife that Scott thought he deserved and he blamed Zelda for his out of control drinking.

They escaped yet again from Paris to Wilmington in September of the same year, but this turned out to be a futile hope for any turning point. Zelda danced as obsessively as Scott drank. Work on The Great Gatsby had stalled and the battle-weary Fitzgeralds returned to Paris for the last time. This time their apartment was in the Rue Palatine right next to the beautiful Saint-Sulpice church in St Germain. Zelda resumed her ballet lessons with Madame Egorova with the same driven intensity as before. She was also having short stories published, another thorn for Scott who was having problems with his own writing. Their marriage now under enormous stress, the Fitzgeralds did what they always did and fled to the Riviera for the summer. Scott was weary, drowning in alcohol, not knowing where he would wake up each morning. Zelda, nervous and underweight, prone to strange pronouncements, had suddenly grabbed the steering wheel of their car and tried to steer them over a cliff. It was clear that Zelda was finally cracking. It was also clear that neither Scott nor Zelda had any idea what to do about it.

Back in Paris Zelda resumed her lessons with Madame Egorova, but she too had noticed the terrible changes in Zelda that could not be dismissed as just extreme anxiety.

In April 1930 Zelda was admitted to the Malmaison hospital just outside Paris but discharged herself less than two weeks later desperate to return to Madame Egorova. Within fourteen days, Zelda was found incoherent and suffering from hallucinations so frightening she had contemplated suicide. This time, there could be no escape from the truth, no running away to another city, another country. Zelda was admitted to Les Rives de Prangins in Switzerland.

In April 1930 Zelda was admitted to the Malmaison hospital just outside Paris but discharged herself less than two weeks later desperate to return to Madame Egorova. Within fourteen days, Zelda was found incoherent and suffering from hallucinations so frightening she had contemplated suicide. This time, there could be no escape from the truth, no running away to another city, another country. Zelda was admitted to Les Rives de Prangins in Switzerland.

She was never to return to Paris again.

Letters between Scott and Zelda throughout their entire life together demonstrate the immense, deep love they had for each other, even when they didn’t like each other, even when each blamed the other for their disappointments and their destructive relationship. Perhaps each of them would have lived an easier, more fulfilling life with another partner but it is doubtful that they would have experienced a greater love, doubtful that Scott would have found the inspiration for so many of his novels without his beloved, infuriating Zelda.

Zelda died on the 10th of March, 1948 in a fire in the Highland Hospital, just outside Asheville in the Blue Ridge Mountains.

She was buried next to Scott in Maryland.

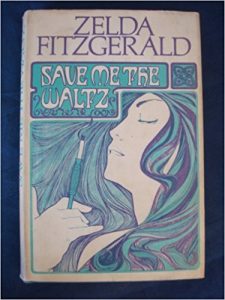

The tormented and often tortuous love story of Zelda and Scott Fitzgerald provided Scott with the inspiration of the majority of his novels. Zelda, too, in Save me the Waltz and her other thinly disguised autobiographical short stories (often to the fury of Scott) leant heavily on the intimacy of their chaotic personal lives.

Lead photo credit : Zelda Fitzgerald in 1917. Public domain.

REPLY

REPLY