The Truth Behind the Paris Opera Captured by Degas

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

The 1500 or more works that Edgar Degas produced of Paris Opera ballerinas in the 19th century showed the artist’s unremitting obsession with the dancers.

Not the dance.

Degas had little interest in the ballet itself. It was movement and realism that he wanted to capture. The artist’s beautiful paintings, seemingly tender and evocative, belied a squalid reality behind the scenes that Degas was well aware of and observed first hand.

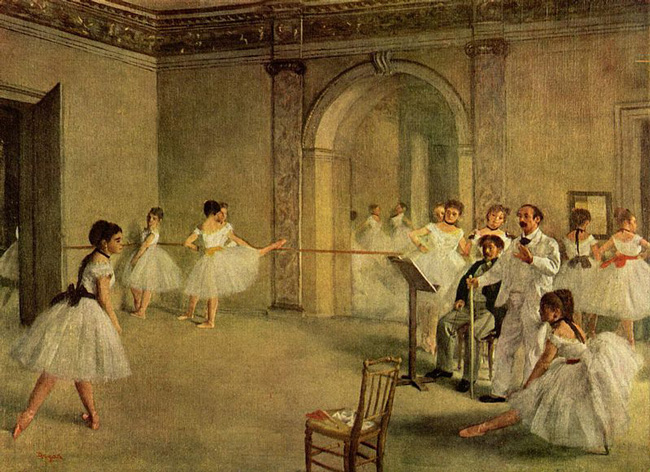

The pitiless truth of the Foyer de la Danse was that this backstage was not a warm-up area for the ballerinas, but functioned as an upper-class meat market.

Edgar Degas: Le Foyer de la danse à l’Opéra de la rue Le Peletier, Musée d’Orsay, Public Domain

For in fact, to all intents and purposes, the Foyer de la Danse was little more than a brothel. The staggeringly opulent exterior and interior of the new Paris Opera was housing something putrid at its core.

The Paris Opera Ballet had been founded in 1669 by King Louis XIV and was the world’s first professional ballet company. Then called the Académie Royale de Danse, the performances were usually held in the French court, and usually performed by male dancers.

Portrait of Louix XIV, the Sun King. Public domain.

By the early 19th century, women had been emboldened to join the ballet. The dancer Marie Taglioni not only went en pointe, feminizing ballet once and for all, but she also shortened her tutu, scandalizing society.

Almost every ballerina who followed Taglioni would suffer exploitation on an industrial scale by men who considered “les petits rats,” as they were called, fair game; favors could be bartered and bought in exchange for their patronage. Indeed, the availability of these young (sometimes very young) women was factored into the design of the Opera House.

Mademoiselle Taglioni poses in dance clothing with her left leg extended, Bernard Mulrenin, Victoria and Albert Museum, Public Domain

Around 1830, Louis Véron, a trained physician who had made his fortune by patenting cough drops, was made the new administrator of the Paris Opera. He was pitiless in his quest to make the Paris Opera profitable. He was the first to create a Foyer de la Danse, a lavish salon backstage. Here wealthy ticket holders known as The Abonnés enjoyed a private theater box plus unfettered access to all the backstage corridors where negotiations for their chosen dancer took place – more often than not, with the mothers of the young girls. Many mothers simply pimped out their daughters to the highest bidder.

Not content with this pressure on these young dancers to sell themselves, Véron went one step further. To encourage the girls to find wealthy protectors, he decreased their wages, leaving them with little choice but to do as he wanted and prostitute themselves.

The Rehearsal Onstage, Edgar Degas, circa 1874, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public Domain

The most affluent patrons were members of the infamous Jockey Club, only too happy to mix a little culture with a lot more sex at the Paris Opera. The Jockey Club consisted solely of aristocrats, devotees of the better things in life – wine, food, horses and needless to say, beautiful young women. The Foyer de la Danse was made for them.

The 19th century in Paris was a time of disparate fortunes. The rich were very rich, the poor were often close to starvation. Prostitution for young women was often their only option, that or hoping to become famous on the stage in whatever metier was possible. Young girls, mainly from profoundly impoverished backgrounds, joined the Paris Opera’s dance school in the hopes of escaping their own certain fate of grinding poverty and maybe, just maybe, making a name for themselves. Few did.

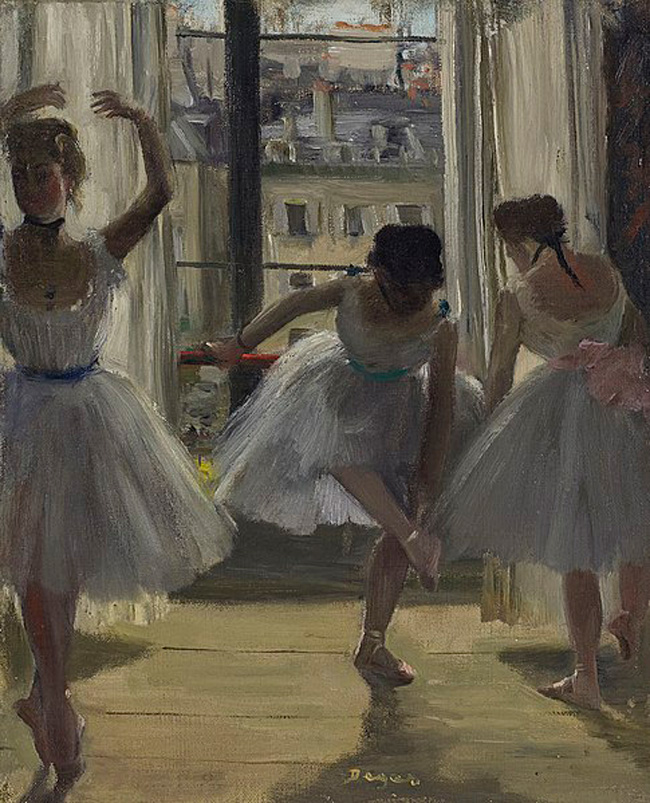

Danseuses dans une salle d’exercice (Trois Danseuses), Edgar Degas, Public Domain

These young girls, often still children, suffered years of grueling training, 12 hours a day, six days a week, with little food or clothing and no lodgings provided. Intense examinations then followed; all endured in the hope of bagging a guaranteed long-term contract. If they were finally accepted, their reward was to be in the hands and whims of The Abonnés after their performances.

When Charles Garnier designed the iconic Palais Garnier, the new Paris Opera house in the 1860s, he took a leaf out of Véron’s book and incorporated yet another lavish room behind the stage as the Foyer de la Danse. For the dancers, nothing had changed. Once more, the room’s main function was not for warming up before a performance, but for wealthy men to ogle the dancers. Backstage was more like an elite men’s club where the men could meet and broker deals while scrutinizing the girls, reveling in their comparative nudity and finally choosing one – or more – for their pleasure.

Grand foyer of Opera Garnier © Αλέξανδρος at Wikicommons

The influence of these affluent patrons and aristocrats can not be underestimated. It was their money that underwrote the Paris Opera, their subscriptions that kept the Paris Opera afloat. The dancers were well aware that the patronage of a powerful man could not only change their lives financially, but also influence the roles they were given in the ballet and their continued employment.

Many ballerinas were trained in the mores of the upper classes, enabling them to mimic their aristocratic providers and become successful courtesans, often to more than one man. Like many famous courtesans, the benevolence of their benefactor was no guarantee of escaping a return to poverty when their beauty or attractions deserted them. For the rare ballerina who had no need of an abonné to support her, she was still tarred with the same brush. In the eyes of the world, she would still be considered a prostitute first and an artiste second. (Emilie Dupré, a dancer from the countryside, was found to be so enchanting that her lovers included the Duc de Mazarin, Duc Louis II de Melun and the regent Phillipe d’Orleans.)

courtesy of the Opéra de Paris

From the sidelines, Degas watched all this dispassionately. Influential friends secured him backstage passes, but he was always there as a voyeur, never a participator. Whether the plight of these young girls concerned Degas is not certain. He made friends with many of the dancers, but in 19th-century Paris this behavior towards young girls was not considered shocking. As well as being obsessed by movement, Degas was an observer, and behind the ostensibly innocent ballet scenes, Degas paintings hinted at much darker goings on. For Degas was foremost a realist painter, avoiding the sentimental, the easy subject. The juxtaposition of the beauty, the costumes, the girls and the dance against the tawdry, blatant transactions behind the scenes, was sure to fascinate even an observer with a less keen eye than Degas.

La Répétition au foyer de la danse, Edgar Degas, Google Art Project, Public Domain

Degas hovered behind the wings, watched rehearsals, ballet classes, and painted them all, but the events in the Foyer de la Dance were more than worthy of his attention. In his 1878 painting L’Etoile, The Abonnés are represented by a dark, elegantly dressed man lurking in the wings. His face is hidden as he observes the dancers curtsying to a curtain call under unflatteringly harsh lighting. In the 1890 painting Dancers, Pink and Green, four ballerinas are adjusting their dresses and their hair before going on stage. Almost obscured by a post, is a rather sinister silhouette of a portly gentleman in top hat observing them. Dancers on the stage, 1876-1877, shows another man quite clearly just off stage.

Dancers, Pink and Green, Edgar Degas, circa 1890, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public Domain

What was blatantly going on behind the scenes of this iconic building was hardly a secret in Paris and beyond. Indeed the Musée Grevin, Paris’s famous wax museum, constructed a tableau of the Foyer de Dance in 1890 showing the The Abonnés being entertained by the young dancers. The tableau was so successful to the public that it remained on display for 11 more years. (Later in 1907, Henri Christiani wrote Petit Rats, the cover depicting very young ballet dancers performing in front of a large, ugly, overpowering gentleman in the ubiquitous top hat. It is not an innocent scene.)

In the meantime Degas had discovered Marie Van Goetham. Marie’s background was archetypal of a “little rat.” Born into poverty, Marie and her sister — with the encouragement of their mother — joined the Paris Opera dance school. Marie was never to be offered a permanent contract, and like many before and after, she was compelled to supplement her tiny income by prostitution. She died in poverty, almost forgotten, except for a certain statue.

A bronze cast of Little Dancer, Aged Fourteen, originally made in 1878-81, Edgar Degas, The Henry P. McIlhenny Collection, Philadelphia Museum of Art @ Regan Vercruysse

Degas had asked her to pose naked at an early age – Marie was hardly in a position to refuse. Degas was often not much kinder to these young girls than the predatory men backstage. He called them “his little monkeys” and demanded they pose for hours on end in painful, contorted positions. These “little rats” were considered expendable, by artists and punters alike.

In 1881, Degas exhibited his wax sculpture of Marie, called Little Dancer Aged Fourteen, at the Impressionist Salon. It was met with such widespread derision and anger, deemed vulgar and bestial, that Degas never exhibited another sculpture in his life. He had dressed the sculpture in a real tutu, point shoes, wig and ribbon. The barely disguised public contempt for ballet dancers was summed up by the critic Mantz, who described her face as a “muzzle” because “the little girl is the beginning of a rat.”

Not surprisingly, Degas had no buyers for La Petite Danseuse de Quatorze Ans. In 2015, the Little Dancer had a conservative value of $23 million.

It was not until 1927 that the exploitation of the “little rats” was addressed. The director of the opera, Jacques Rouche, backed by Serge Lifar, the new Ballet Master, banned The Abonnés from all access backstage — to howls of outrage.

The ballet was finally turning into as respected an art form as opera.

Lead photo credit : Ballet at the Paris Opéra, Edgar Degas, 1877, Art Institute of Chicago Collection, Public Domain

More in ballet, dance, Degas, Edgar Degas, Les Petits Rats, Paris Garnier, Paris Opera

REPLY

REPLY