The Spirits of Montmartre: The Paris of the Impressionists

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

As France celebrates the 150th anniversary of Impressionism, Anne Price examines the historic importance of Montmartre for these artists

A decapitated Christian Bishop carrying his head before him like a ventriloquist’s dummy as he walks several miles while delivering a sermon, is not what springs to mind in association with Montmartre; nor does the name of the first tour guide to the butte, King Dagobert 1st, automatically trip off the tongue, even though ancient records show that every seven years, he led groups of pilgrims to visit the site where Saint Denis, the Bishop of Paris, had died.

The cobbled streets of Montmartre – which lead up to the Sacré-Cœur Basilica, sitting like a glorious sugar concoction on its throne overlooking the city – hide beneath them the voices of the past waiting to tell their stories. In its time, Montmartre has been a burial place for the bones of persecuted Christians and the site of a prestigious Benedictine Abbey founded by Louis VI, whose buildings and gardens covered the whole of the hill until it was destroyed during the French Revolution in 1790; at the same time a 17th century priory was destroyed to make way for gypsum mines. It has twice been used as a vantage point from which to attack the city with artillery, first by Henry IV during the Siege of Paris in 1590, then by Russian soldiers during the Battle of Paris in 1814. It became the focal point of the revolutionary uprising of the Paris Commune in 1871. All this before the names of a group of revolutionary artists became synonymous with Montmartre.

Statue of Saint Denis, the first bishop of Paris. © L. Benkard/Flickr

From the 15th century, Montmartre was initially a rural village surrounded by vineyards, orchards and 13 working windmills, without a cancan in sight! In 1785, a tax wall was built around Paris, and Montmartre, being outside the walls, became a tax haven for businesses wanting to avoid taxation. Cafes and bars sprang up to serve them. In 1860, it was once again incorporated into Paris and soon became a renowned hub for art in Paris.

It went from being a vantage point from which army commanders attacked the city, to a place from where artists could capture in their paintings, its picturesque charm and its spectacular views over Paris. Montmartre soon became a melting pot for a group of disenfranchised artists disillusioned with the conservative academism of the Royal Academy of Painting and sculpture, which they perceived as being stuck in a bygone era. It was here that the Impressionist saga began.

Cannons of Paris brought to Montmartre. (1789) Jean-Louis Prieur, musée de la Révolution française, Vizille. Wikimedia commons

Vincent van Gogh, La Colline de Montmartre ou Vue de Montmartre et de ses moulins (1886), Otterlo, musée Kröller-Müller. Public domain

Today, the old village still exists on the top of the hill, centered around Place du Tertre. In this open-air studio, many artists still come to display their work and create portraits of passers-by. Montmartre’s most famous square, it straddles the site of the ancient Benedictine abbey. It is here that local artists met to discuss painting and politics, mix with working class people and paint their favorite models, who often became their lovers.

This colorful, decadent image of Montmartre has endured since the 19th century but its history has its roots buried deep in Gallo-Roman times, when the city was called Lutetia. Its story is the stuff of Romantic painting, the kind of subject the Impressionists were trying to break free from. The distant voices of this young, revolutionary group of artists, writers and intellectuals of the 19th and 20th centuries mingle with the whispers of revolutionaries of a different kind. The multitudes of present-day sightseers treading the cobblestones to stand before the grace and grandeur of the 19th century Sacre-Coeur, rub shoulders with the spirits of free-thinking artists as they walk over the bones of long forgotten tourists on a very different pilgrimage.

Place du Tertre, Paris. Credit: Pierre Blaché

They were early Christians making the journey to the Butte of Montmartre to visit the site where the legendary 3rd century Christian martyr, Denis of Paris, and his two companions, Rusticus and Eleutherius, victims of their own success in preaching Christianity, lost their heads. Pagan priests, alarmed over their loss of followers, shouted “off with their heads” to the Roman governor. Unlike Alice in Wonderland, they did not escape, but were marched to the top of the hill, and decapitated by a Roman soldier. In a way that is as surreal as Lewis Carol’s book, Denis did not lose his head but picked it up and walked for several miles while delivering a sermon. The hill, a possible pagan holy site, became known as Mons Martyrum, today’s Montmartre. It became a place of popular pilgrimage and was the burial place of many Christians, whose souls lie in a quarry on the side of the hill in the “field of the dead.”

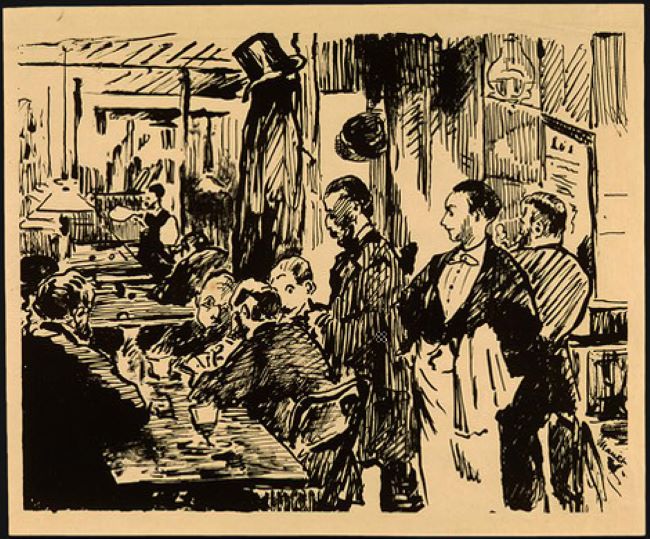

Au Café, by Édouard Manet, depicting the Café Guerbois. National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

A completely different kind of journey took place during the Belle Epoque from 1872 to 1914. Many artists flocked to Montmartre where the rents were low and the atmosphere conducive to controversial thought. Like the silenced past-crusaders, they had a message, which grew into a belief. Montmartre rapidly became the center of avant-garde Parisian art, gaining notoriety as a bohemian district where its decadent culture thrived in the raucous café-concerts and outrageous cabarets. Its radical politics and underground culture mocked the Third Republic’s bourgeois morality and increasingly corrupt government.

Artists like Renoir, Manet, Degas, Cézanne as well as Berthe Morisot and Pissarro were regular visitors to cafes such as the Café Guerbois on the grande rue des Batignolles, where they met to discuss their approach to art. Among them was Cézanne’s childhood friend, the writer Emile Zola, an influential critic and their strongest supporter. It was here that Monet first suggested holding an independent group exhibition in December 1873.

Le moulin de la Galette. Photo credit: Son of Groucho from Scotland / Wikimedia commons

The ordinary people with whom they mixed in Montmartre were a source of inspiration for the Impressionists, as were the working-class dance-halls. The Moulin de la Galette, situated on the Butte, was another popular meeting place for the Impressionists. Its iconic double windmills became the first architectural symbol of Montmartre’s bohemian culture and its vibrant energy is captured in Renoir’s painting Le Bal du Moulin de Galette (1876).

Bal du moulin de la Galette, Auguste Renoir, 1876. © Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

The notorious Moulin Rouge, the birthplace of the French Cancan, which came to symbolize Montmartre’s decadent artistic society, opened its doors in 1889 at the foot of the hill. Le Chat Noir also became a popular haunt for artists and writers. By the last quarter of the 19th century, the blurring of class boundaries contributed to Montmartre’s reputation as a place for escape, pleasure, entertainment, and sexual freedom.

Today, Montmartre is an officially designated historic district with limited development allowed. It is not difficult to conjure up a quirky image of Saint Denis holding up his head to peer quizzically over the crowds of tourists mingling with the ghosts of the past, whose dusty relics lie beneath their feet.

Lead photo credit : Montmartre. Photo credit: Patrick K/Flickr

More in Montmartre

REPLY