The Monuments Woman: The French Spy who Rescued Stolen Art

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

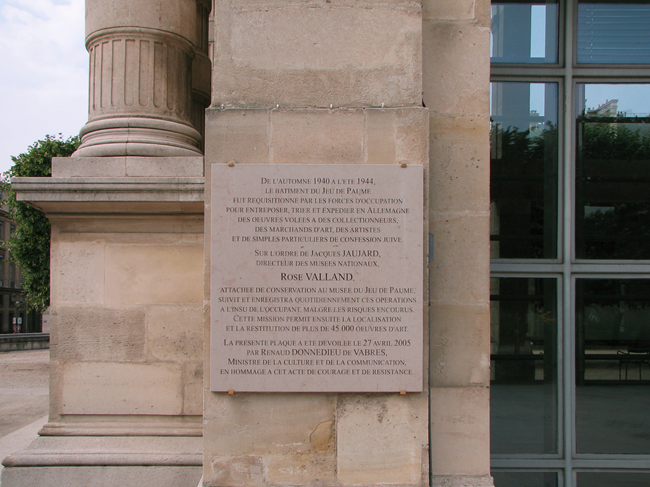

There is a plaque on the wall of the Jeu de Paume, in the Tuileries Gardens, which commemorates one of World War II’s least-known heroines: Rose Valland. She was an art curator at the museum who single-handedly ensured that thousands of works of art stolen by the Nazis could be traced and, finally, repatriated to their rightful owners. While other Resistance heroines, such as Germaine Tillion and Geneviève de Gaulle, have been gradually acknowledged (at least in France) for their roles during the war, Rose Valland has remained unknown to most people.

Rose was born in 1898 in the Isère department, deepest provincial France. Her father was a modest blacksmith. She won a scholarship to train as an art teacher, followed up with further studies at the Écoles des Beaux-Arts in Lyon and Paris. Throughout the late 1920s and early 1930s, she studied art history while working, and she obtained a special diploma from the École du Louvre in 1933. The previous year she had become a volunteer curator at the Jeu de Paume, home to the nation’s biggest collection of Impressionist paintings at the time.

Portrait of Rose Valland. Unknown photographer. Public Domain. Wikimedia Commons

In 1938 Rose took charge of the museum when its director fell ill. On the orders of Jacques Jaujard, directeur des Musées Nationaux, she stayed at the Jeu de Paume when the Nazis arrived in 1940. At that point she was given a job at the ERR (Reich Leader Rosenberg Institute), whose role was to oversee the removal of works of art to Germany. These artworks had been looted and stolen from museums and private collections, many owned by Jews who were deported. The Jeu de Paume served as a central storage and sorting depot before the works were sent to Germany.

On Jaujard’s instructions Rose became a spy ‘on the inside’, feeding information to her former boss, who passed it on to the Resistance. As crates of art moved through the Jeu de Paume, she meticulously, and secretly, recorded the contents in private notebooks, noting the names of their rightful owners, where the works had come from, and their precise destinations in Germany. (Jaujard is another unsung war hero. He had overseen the removal of the Louvre’s most famous and priceless works in the weeks leading up to the German invasion, ensuring that they remained safely hidden in obscure cellars, attics and even caves all over France.)

The risks of being discovered were very real. Rose took advantage of her unobtrusive, bespectacled appearance and the Germans’ dismissive attitude towards her, treating her like a secretary. They did not seem aware that she was actually a qualified and highly knowledgeable art historian. She certainly never let on that she understood German – she had picked up a working grasp of the language from regular visits in the 1920s and 30s. This skill proved invaluable for eavesdropping on conversations to learn about the provenance and eventual destinations of all those crates. In addition, she would glean information from talking to French truck drivers working for the Nazis. She noted train schedules and passed on information about their movements which helped the Resistance avoid bombing certain trains or railway lines when they knew an art shipment was passing through.

There is no doubt that Rose risked her life undertaking this work and several times she was nearly discovered. Once she was actually caught by the official acting as Goering’s art dealer in the act of copying information. On being sternly warned that she could be shot for revealing secrets, Rose calmly replied that anyone doing such a thing would be an idiot. If she was found looking through the paintings she would claim to be merely an enthusiast admiring them. Several times she was dismissed but somehow she managed to return. After the war, she discovered that the Germans had, in fact, suspected her and had plans to arrest and deport her – plans which, fortunately, were never carried out.

Rose Valland’s personal effects displayed at the Musée dauphinois in the Isère. Photo credit: Patafisik / Wikimedia commons

Around 20,000 works of art passed through the Jeu de Paume – a fraction of the total stolen overall but still a significant number that were traced after the war. Rose’s sense of patriotism could only have been fueled by witnessing numerous high-ranking Nazi officials choosing art for themselves – including over 20 “shopping trips” by Hermann Goering. She later described bonfires of so-called “decadent” art (ie. modern and contemporary artists such as Picasso, Braque, Modigliani etc.) as “slaughter.”

For Rose, Liberation did not mean the end of fear and anxiety. Having worked for the Nazis she was vulnerable to being accused of collaboration and it took months to persuade the Allied authorities of her real role. Her detailed notebooks undoubtedly helped, and the influence of Jaujard. Initially very wary of the Allies, over time Rose forged an enduring relationship with the American placed in charge of finding and repatriating stolen Nazi art, Lieutenant James Rorimer, in civilian life the director of the Metropolitan Museum. War was still raging in Europe and the first priority was to protect the art already in Germany. Rose handed over her lists of locations and this prevented them being by bombed by the Allies before the art could be retrieved.

A commemorative plaque at 4 rue de Navarre, where Rose Valland lived in the 5th arrondissement. Photo credit: TCY / Wikimedia commons

The war over, Rose’s priority was the restitution of France’s artistic heritage and she joined the French Army, first as a lieutenant, then as a captain, to join the “Monuments Men” team (which did contain women other than Rose). She testified at the Nuremberg Trials, in front of Goering, and called for the destruction and expatriation of art to be considered a war crime. She then spent seven years in Berlin, moving around the Russian Zone – itself dangerous enough – among other activities, bribing officials with cognac to find out where artworks were hidden. On one occasion she smuggled two lions from Goering’s house in the back of a truck and covered in gravel.

Rose received fulsome acknowledgement of her achievements in the years after the War, which might make her subsequent obscurity all the more surprising. In Jaujard’s report of the war, he spends eight pages recounting Rose’s work, and Rorimer called her “a heroine” who was “the one person who above all others enabled us to track down the official Nazi art looters.” Jaujard ensured she received the Legion of Honor and Medal of Honor, and in the U.S. she was awarded the Medal of Freedom.

One reason for her later fall into obscurity might well be old-fashioned misogyny: the art world was very male-dominated, and in addition, Rose didn’t “belong” in other ways: she was working-class, qualified through hard work including evening classes, and she had a reputation for being outspoken. She was also a lesbian and although she never “came out,” her relationship with a British translator Joyce Helen Heer was widely known.

The rose variety named for Rose Valland. Photo Credit: Patafisik/Wikimedia Commons

Once more a civilian in France, Rose finally was given the title of curator in 1953. She was recognized as a respected authority on Nazi-looted art and remained committed to the cause of restitution. As well as the estimated 22,000 works documented at the Jeu de Paume, she was instrumental in recovering some 60,000 by the Monuments Men, of which 45,000 were returned to their owners. Her archives remain a valuable resource in the recovery of stolen World War II art.

In Le Front de l’Art, her book describing her war work, she displays a wry sense of humor: she quotes a Nazi report warning that access to the Jeu de Paume should be heavily restricted, or it would become very convenient for espionage. She adds that the writer “wasn’t wrong!” But she never sought the limelight, and perhaps this is another reason why she gradually became semi-forgotten as one of France’s wartime heroines. Her death in 1980 merited a service at the Invalides but her funeral was attended by only a handful of people.

Actress Suzanne Flon played the character of Rose Valland in John Frankenheimers film Le Train (1964). Public domain

But things may be starting to change. As well as the plaque (mounted in 2005), her life has been turned into a play, Rose Valland : Sauver un peu de la beauté du monde (Saving a Little Bit of Beauty in the World) and in 2023 the American writer Michelle Young wrote her story in The Art Spy. Also in 2023, a petition was launched to put Rose into the Panthéon. Although it has a long way to go, the campaign deserves to succeed; if it does, Rose Valland would become just the sixth woman to enter the Panthéon, her wartime achievements equalling those of Germaine Tillion, Geneviève de Gaulle and Josephine Baker who already rest there.

Lead photo credit : Galerie nationale du Jeu de Paume. Photo Credit: TCY/Wikimedia Commons

More in history, World War II

REPLY

REPLY