Françoise Gilot: Surviving Picasso

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Update: Françoise Gilot passed away on June 6, 2023 at Mt. Sinai Hospital West, New York City. She was 101 years old.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of Pablo Picasso’s death and many exhibits have been organized in Europe and the United States to celebrate his work. There’s also been much analysis and media coverage exploring his influence and legacy such as this thought-provoking New York Times piece, “Picasso: Love Him? Hate Him?”

Of all Pablo Picasso’s partners, only one of them walked away.

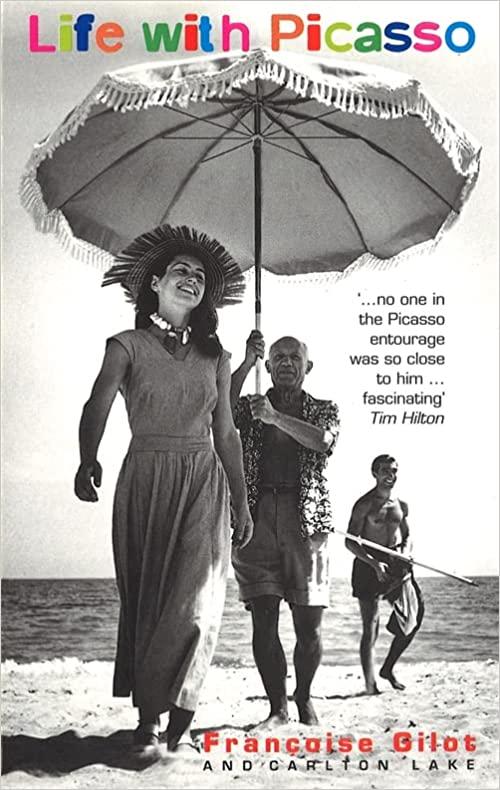

Françoise Gilot may not have walked away unscathed, but she certainly remained unbowed. However, when she wrote Life with Picasso in 1964, she paid a heavy price for her defection.

Furious at her revelations, Picasso unsuccessfully attempted to stop the book’s publication and subsequently disowned not only Gilot but also their two children. Such was Picasso’s influence that many of their mutual friends shunned her and started a petition to have her book banned in France (only Jean Cocteau remained loyal). Eventually Gilot felt compelled to leave France, where she believed she was hated. Certainly art galleries no longer wanted to display her work, and agents would not represent her, fearing Picasso’s displeasure.

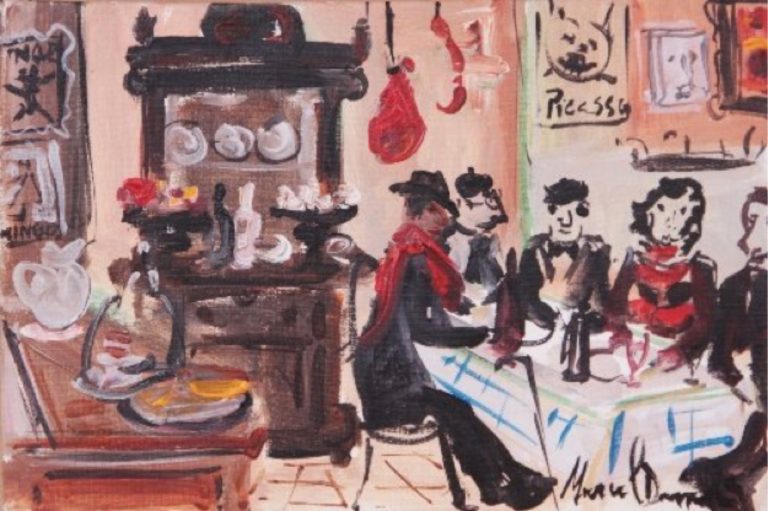

The Second World War was still in progress 1943 when Gilot and Picasso first met in Le Catalan, a small restaurant in Rue des Grand-Augustins on the Left Bank where Picasso had his studio. Gilot was 21 years old and Picasso was 62. Picasso invited her to his studio. Gilot claims that despite her inexperience, she always knew what this would eventually mean, but she could not have failed to be deeply affected by the great artist’s interest in both her and her drawings.

At the time Picasso was still with Dora Maar, although Maar never lived in Rue des Grandes Augustins with Picasso but around the corner. Their affair had lasted almost nine years from 1937, and Maar— a talented artist and photographer — suffered a breakdown when Picasso abandoned her for Gilot. It was a pattern that Picasso continued to repeat, replacing one lover with another, with often disastrous consequences for the discarded partner. Gilot was well aware of Picasso’s track record; she had met Maar numerous times, and both she and Picasso were often besieged by his tempestuous wife, the former Russian ballet dancer, Olga Khokhlova.

(Khokhlova refused to divorce Picasso, but he also dragged his heels to prevent sharing any of his assets. In return, Khohklova hounded Picasso and Gilot whenever she could. In a quirk of French law, a marriage ceremony involving two foreigners could only be dissolved in accordance with the laws of the husband’s country. The government having been overthrown in the Spanish Civil War, and now under Franco’s regime, did not permit a Spanish subject who had been married in church to divorce. Khoklova and Picasso remained married until her death in 1955.)

Marcel Duval (1890 – 1985), Restaurant Le Catalan, 19 Rue des Grands-Augustins

At first in Paris, Gilot lived with her grandmother, visiting Picasso’s studio as often as she thought appropriate. But she neither played games with the artist nor encouraged his attempts at seduction. Picasso was doubtless intrigued by this calm young woman who was not overwhelmed by his reputation but could converse with him on an equal intellectual level. Gilot had reservations about moving in with Picasso. She had fallen in love with him but was very aware of the disparities in their temperaments and was uneasy about his fractured relationship with Dora Maar. It was not until May of 1946 that Picasso finally persuaded her to move into his apartment on the Rue des Grands-Augustins.

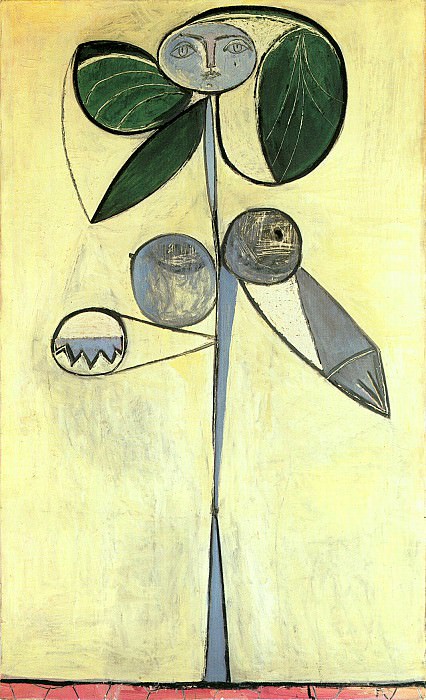

Pablo Picasso, Femme Fleur

As with Picasso’s previous lovers, Gilot became his model and muse. La Femme-Fleur was the first he painted of her after she began living with him. Gilot had taken her time to agree to move in with Picasso because she was clear-headed about what it would involve. She would devote herself to him – his needs would be paramount. Treading the line between “Goddess and Doormat” (Picasso’s definition of women) was not always easy, but Gilot had determined to remain a Goddess. She was tested almost immediately when Picasso took her to Ménerbes in the south of France for the summer. They stayed in the house that Picasso had given to Dora Maar with all its tangible memories, and Marie-Thérèse Walter — with whom he became involved when she was 17 years old, and fathered a child — wrote daily. Picasso read these letters aloud to Gilot with great affection. Uncomfortable, Gilot tried to make her escape. She was caught by Picasso and his driver on the road. The argument that ensued persuaded Gilot of Picasso’s love. Three weeks later, to the joy of Picasso, she discovered she was pregnant with their son, Claude.

Pablo Picasso, Portrait de Françoise, 1946, Crayon graphite sur papier, 66 x 50,5 cm, Musée national Picasso-Paris, MP1351 CopyrightRMN-Grand Palais (Musée national Picasso-Paris) © Succession Picasso 2022

Although Gilot continued painting throughout her time with Picasso, she mentioned it very little in Life with Picasso. The book is about the artist, his work, his conversations, his friends. It is clear that Gilot was no doormat, but neither was she independent. Picasso made her rise at 5:30 a.m. to light the fire in his studio. They had servants who could have done this just as easily. He could be intransigent, petty about small things, bad tempered and often insulting. At his request, Gilot took over his finances and his correspondence — which could lie unopened and unanswered for months. She also counted the cash in his trunk whenever he suspected it might no longer be there, and generally ran his household. There was another child after Claude, Paloma, and Gilot was often tired. However life with Picasso was never dull and the company of his illustrious friends stimulating beyond measure. Just a few of the many visitors to the rue des Grands-Augustins: Henri Matisse, Paul Éluard, André Breton, Guillaume Apollinaire, Jean Cocteau, Gertrude Stein and Alberto Giacometti.

Hôtel d’Hercule, 7 rue des Grands-Augustins. Photo credit: Celette/ Wikimedia commons

Summers were spent in Vallauris— Picasso had become fascinated by ceramics — but their return to a cold, damp Paris in winter depleted Gilot’s reserves and she was often ill. She began to sense that Picasso was withdrawing from her and the domesticity of family life.

He still adored the children, but Gilot felt that she was becoming more like an employee than a partner. From spending every day together, Picasso began taking trips without her. He criticized her looks, telling her that she looked like a broom, she had become so thin. Gilot knew that the writing was on the wall. Right at the beginning of their affair, Picasso had told her that any love could only exist for a predetermined period. Fernando Olivier, Marie-Thérèse Walter, Olga Khohklova and Dora Maar were the inescapable proof of that.

In 1951, the family were in Vallauris when rumors of Picasso having an affair with a girl in St Tropez reached Gilot’s ears. Picasso denied it but Gilot knew it was true and began her own quiet withdrawal. Picasso did not want her to leave him, indeed did not believe she ever would leave him, but refused to change his behavior, still leaving Gilot alone with the children for long periods of time. Perhaps it was these times without Picasso that hardened her resolve to break away, and in 1953 she left Picasso, and with her children returned to Paris. During the autumn of 1952, she had known her replacement was already waiting in the wings. Obsessed with Picasso, the 25-year-old Jacqueline Roque was submissive and devoted to him until the day he died.

“On the Way,” oil on canvas, by Françoise Gilot, 2004 (exhibition in Hong Kong, November 2021). Photo credit: ESIG HIPWOUAo / Wikimedia Commons

As for Gilot, there was a short-lived marriage and another daughter, but her time in France was running out. She had never been forgiven for leaving Picasso and for remarrying. Gallery owners were still reluctant to show her work, but the publication of her book was the final straw for her career in France and she left Paris for a new life in New York.

In New York, Gilot flourished. She married the illustrious scientist Dr Jonas E Salk, who developed the vaccine against polio, and continued painting with much success, her paintings selling in the U.S and abroad for hundreds of thousands of dollars. Finally in 2021, the Estrine Museum in Saint-Remy de Provence hosted the first exhibition of Gilot’s work. The director of the museum, Elisa Farran, said that the motivation for the exhibition was the art world’s injustice towards women. Some 20,000 visitors finally saw Gilot’s paintings for the first time in France. The exhibition, entitled “The French Years,” showed Gilot’s work in the 1940s and displayed the great talent she had even at such a young age. The sadness is that Gilot, then 99 years old, was unable to travel from New York to St Remy to see it, and be vindicated for her enforced time in the artistic wilderness in France.

Françoise Gilot during an interview in 2013. Wikimedia Commons

Now 101 years old with all her faculties, Gilot still paints. She’s proved that she not only survived Picasso, but survived with wit and humor and no regrets.

Footnote: What still surprises is the backlash her book provoked. The book is neither vitriolic nor scandalous. She does not demonize Picasso; indeed his faults and capriciousness were known to all who later shunned Gilot. She dedicated the book “To Pablo.” The dedication could just as easily have been “To Pablo, with love.”

Lead photo credit : Françoise Gilot, Self Portrait, 1970, watercolor on paper, 64,8 x 50,2 cm. (25.5 x 19.8 in.)

REPLY

REPLY