Blaise Pascal’s Omnibus: The First Mass Transport System in Paris

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Before the 19th century, getting around Paris was a dirty and messy business. Picture the scene in the 1660s: many streets were unpaved, hardly any had sidewalks. Two centuries before Haussmann opened up the city with his wide boulevards, even the principal thoroughfares were narrow and congested. In the summer the roads threw up clouds of dust; in winter they were muddy quagmires. Add to that the piles of garbage from businesses and private dwellings, primitive drainage and the excrement from hundreds of horses and stray animals and — well — you can imagine what the streets were like. Not a place where you would want to walk if you could avoid it.

The problem was, the vast majority of people had no choice but to walk. If you were very rich you would have a carriage. Other carriages, known as fiacres, were available for private hire or “coach-sharing” but were expensive. If you wanted to get from A to B quickly you could use a sedan chair – a single-person covered box that was carried in front and behind by manservants. But even these were mainly the preserve of wealthy people. Everyone else walked. Women wore pattens – platform-soled wooden mules that fitted over their normal shoes and lifted their feet and skirts slightly above the ground in an attempt to keep them clean.

Le Fiacre, Luna, Charles de (Chalon-sur-Saône, 1812), peintre. 1845. Musée Carnavalet, Histoire de Paris

In a city of half a million people, what Parisians needed was a system of getting around that was affordable and clean. In the 1660s the inventor, mathematician and philosopher Blaise Pascal designed just that: the world’s first public transportation system.

Pascal already had a bit of a reputation as an innovator. In 1642, inspired by his father’s work as a supervisor of taxes, he invented his Arithmetic Machine. This was a mechanical calculator that added, subtracted, multiplied and divided numbers to help people employed in making laborious calculations. Although Louis XIV granted Pascal a royal privilege (an early form of patent), Pascal failed to capitalize on his advantage and the Arithmetic Machine was not a commercial success.

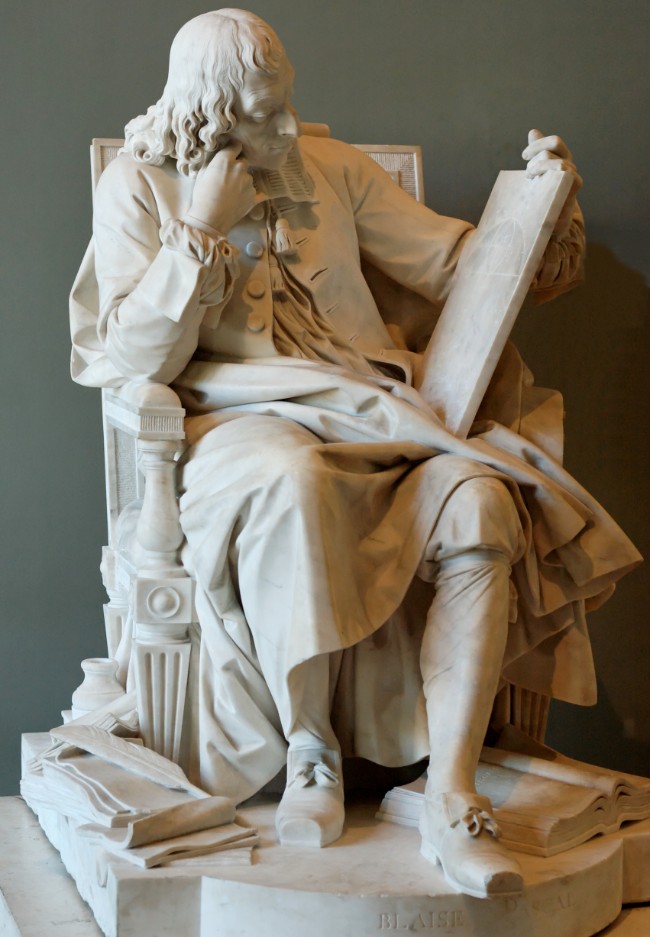

A marble sculpture of Blaise Pascal by Augustin Pajou (1785), musée du Louvre. Wikimedia commons/ public domain

The public transport scheme was a completely different proposition. It was underwritten by the Duc de Roannez — sword-carrier at Louis XIV’s coronation and already a friend and business partner of Pascal: together they had been involved in a marsh-draining scheme in Poitou. A third partner in this enterprise had been the Marquis de Crenan and he came on board again. The Duc de Roannez held half the shares, with Pascal, Crenan and a fourth partner, the Marquis de Sourches, sharing the remaining 50 percent. This hugely spread the financial risk as far as Pascal was concerned.

From the start, the group had two clear ideas about the new scheme: as far as was practicable it would transpose to an urban setting the already-established network of coaches that crossed the French countryside, and it would be aimed at the upper middle class. The first tactic had the advantage of promoting a service that Parisians could already visualize and therefore not be scared off by its innovation. The second ensured that a profitable fare could be charged.

Wood model of the carrosse à cins sols. l’espace Blaise Pascal du Musée Lecoq. Wikimedia commons

This new urban public transport system would have fixed routes, fixed fares and a fixed timetable. Nothing like this had been tried before. The first line ran from Rue Saint Antoine to the Palais du Luxembourg (linking the homes of Pascal and Roannez — how convenient!) via the Quai de la Mégisserie, Place Dauphine, Pont Neuf and Rue de Tournon. The fare was set at five sols, or sous. In modern money that equates to around 15 euros so roughly the price of a taxi ride — not cheap and beyond the means of working-class people, but affordable for affluent professionals. More pertinently, it was the average price you paid for a private Mass, or the daily wage of a soldier so it was a sum of money that people were familiar with. There were fixed stops and the driver would halt on request. Carriages would pass at 15-minute intervals between the hours of 7 am to 8 pm (6 am to 9 pm in summer). Some lines intersected and you could change routes along the way upon payment of another five sous. Each carriage could carry eight passengers and sported the coat of arms of the City of Paris, giving the fleet a distinct identity, no different from today’s RATP. Even the driver and lackey wore blue smocks bearing the coat of arms and those of the king. You even had to pay the exact fare — no change given. In all its essential elements it was very similar to modern urban transport systems.

A commemorative plaque honoring the 350th anniversary of Pascal’s public transport invention. Photo credit: Stevebehr / Wikimedia commons

The service, called Les Carrosses à Cinq Sols, or The Five Sou Carriages, launched on March 18th, 1662. Fears that it would be ridiculed and ignored by Parisians were unfounded and it was an immediate success. Extra lines swiftly followed: line 2 between Rue Saint Antoine and Rue Saint Honoré opened in April, line 3 linking the Palais du Luxembourg and Rue Montmartre in May, and line 4 in June. This line was a bit different: it was a kind of Outer Circular route. Because it was so much longer than the others, this route was broken up into “fare stages”; if you traveled through more than two stages you had to pay another five sous. So yet another innovation was the principle of incremental fares.

Along the route officials in little offices (probably more like kiosks) collected the extra fares. Finally, a fifth line between Luxembourg and Rue de Poitou in the Haut Marais opened in July. Sadly, Pascal barely had time to see his enterprise succeed. He died in August 1662.

Statue of Pascal under the Tour Saint-Jacques in Paris where he is said to have repeated his experiments at the Puy de Dôme on atmospheric pressure and the gravity of the air. Photo credit: LPLT / Wikimedia commons

But despite its initial success, the Carrosses à Cinq Sols was a short-lived enterprise. It isn’t documented why or how exactly it failed but historians have suggested a few reasons. For a start, certain types of people were actually forbidden to use the service: soldiers, liveried servants, and workmen specifically. This, unsurprisingly, caused discontent among the majority of the population. While the desired clientele of haut bourgeois was ruthlessly targeted, this inevitably limited the number of potential customers.

Another likely cause for people falling out of love with it was that just as now, pickpockets were commonplace. No doubt this put off many upstanding middle class people from using the carriages. Furthermore, the carriages were very clearly associated with the official regime. Their distinctive livery made them a target for anti-establishment and anti-monarchist troublemakers and Pascal exhaustively tested the vehicles against the risk of them being overturned.

Plaque at no. 54 rue Monsieur-le-Prince (formerly rue des Francs-Bourgeois-Saint-Michel), where Pascal lived from 1654 to 1662. Photo credit: FLLL/ Wikimedia commons

But in the end, the main reason for the enterprise’s failure was probably the most obvious: it was an idea ahead of its time. In the 1660s the majority of people still worked close to where they lived. However dirty the streets, it only took five or 10 minutes to walk home. Many people lived their entire lives in their quartier and the idea of traveling across Paris on a regular basis was quite an alien concept to them. In the end, there were probably not enough people who needed the service to make it profitable.

Gradually, people became more and more disenchanted with the service and after the successful early years, use of the Carrosses à Cinq Sols started to decline. The owners tried raising the fare to six sous but that failed. Eventually, it closed down around 1677.

It would be the late 1820s before another public transportation system in Paris got off the ground. It’s a shame that the Carrosse à Cinq Sols didn’t succeed for it was an innovative solution to an urban problem that plagued Paris for another 150 years.

Lead photo credit : The Paris network map of the carrosses à cinq sols by Jouvin de Rochefort from 1672 description of the première route: Les Ancêtres de l'Omnibus (Le Petit Journal. Supplément illustré), 6 October 1912

REPLY

REPLY