Vivre Sa Mort: The Passing of Film Giant Jean-Luc Godard at 92

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Jean-Luc Godard, the director who spearheaded the Nouvelle Vague and became perhaps France’s greatest filmmaker of the 20th century (one might throw in the 21st for good measure), has died as willfully as he lived. Godard was cantankerously opinionated as ever until fairly recently but developed “pathologies” affecting his quality of life. He opted for assisted suicide, which is legal in Switzerland, where he lived for many years.

The Franco-Swiss Godard’s youth and student years were indelibly associated with Paris. The late 1950s saw the death throes of France’s Fourth Republic and the colonial debacles in Algeria and Dien Bien Phu. France’s old institutions, including its cinema, were being called into question. Godard was influenced not only by his Swiss Protestant background, moralistic and nonconformist, but also by the prevailing mood of French artists and intellectuals, who were turning against the influence of America’s materialistic culture in favor of leftist idealism.

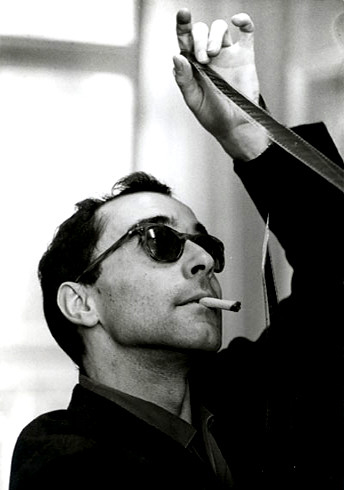

Jean-Luc Godard © Shutterstock

The young Godard found refuge in two institutions that still had integrity: the Cinémathèque Française and the magazine Cahiers du Cinéma. He began as an irascible critic lacerating conventional French cinema but praising the Hollywood films of directors like Howard Hawks. Godard and his fellow Cahiers critic François Truffaut soon put their money (what little they had) where their mouth was, making a short film called Une Histoire d’Eau.

The New Wave was inspired by Italian neo-realism, with the additional influences of Jean Rouch’s great ethnographic documentaries and Hollywood genre films. Une Histoire d’Eau is one-part documentary, about a massive flood that had struck France (with much real footage), but with a screwball rom-com narrative. That movie laid the groundwork for Godard’s first feature, Breathless (A Bout de Souffle).

That movie was another screwball romance, with a hardboiled crime story giving it a darker hue. Godard paid homage to Hollywood but with a backhanded critique, showing how the Bogart clichés led to the hero’s demise, and the charming American girlfriend was a femme fatale in the most literal sense. Breathless had the advantage of a Truffaut script, and two charismatic young stars, Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg. Shot on location, Godard extended his improvisatory ethos, resulting in a style that was new and kinetic. As fast as one of his jump-cuts, he and Truffaut, who’d had a big success with Les 400 Coups, were at the forefront of a new generation of French filmmakers.

The young director made films at a lightning pace: Le Petit Soldat (1960), Une Femme Est Une Femme (1961), Vivre Sa Vie (1962), Les Carabiniers (1963). Le Mepris (1963), Bande à Part (1964). Une Famme Mariée (1964), Alphaville (1965), Pierrot le Fou (1965), Masculin/Feminin (1966) … and more. Conventional narrative was mostly, if not entirely, left behind, as he embraced essayistic techniques and internal monologue voice-over. (Le Mepris, or Contempt, was an exception: based on an Alberto Moravia novel, starring Brigitte Bardot, and produced by Carlo Ponti, it was more grounded and became one of his few commercial hits.) Otherwise, the scripts became more improvised, the filming more exploratory. Film by film, the reaches of his style, technique, and vision expanded exponentially. Godard became an iconic brand, like Kubrick or Fellini. Their renown may have surpassed his, but those who revered Godard were the young, filmmakers, and other artists.

One obsessive interest of his was how mass culture turned the cityscape, and modern society in general, into a jungle of signs, images, texts. He was as fascinated by that as he’d been with old Hollywood motifs. At the same time his films continued his critique of American (but increasingly global) commercial values—“Coca-Colonization.”

Actually, Godard had a few missed opportunities with America. When David Newman and Robert Benton wrote Bonnie and Clyde, their first choice for director was Godard. When he couldn’t or wouldn’t take the helm, they entrusted the film to Arthur Penn. Godard had his own American dream project, a film called One American Movie. This too, never came off in its envisaged form. A more charming American interlude for Godard was an appearance on the Dick Cavett Show (watch below). Godard’s English was surprisingly fluent and elegant. He offered the usual Godardian paradoxes to an admiring Cavett and rapturous live audience, but more gently than in his French media appearances.

With his face stubble, tinted glasses, dishevelled clothes and cigar, Godard looked like a latterday Bertolt Brecht. Like Brecht he was an unclassifiable artist of the left. When he got too close to French hot-button issues in the early Le Petit Soldat, about the Algerian war and rightist terrorism, the film was banned by the authorities. (It was in that film that Godard gave us the famous quote about cinema, that it’s “truth 24 times a second”).

Godard kept on probing and critiquing politics. He contributed a segment to the anti-war anthology film Loin de Vietnam (Far From Vietnam, 1967). La Chinoise (1967) about Maoist students in Nanterre predicted the student protests that happened in ’68, instigated by students from … Nanterre. Le Weekend (1968), his masterpiece of that decade, presented a sweeping Boschian view of consumer society in the form of an endless (and bloody) traffic jam. During the May 1968 revolt, he and Truffaut took an active part, forcing the closing of the Cannes film festival.

Still from Loin du Vietnam (1967). Photo by Mannhai at Creative Commons

In his personal life, the young Godard tended to get involved with his leading ladies. He married both Anna Karina and Anne Wiazemski. Each became his muse and appeared in several of his films. He divorced both soon after. However in his later years he had a lasting marriage with Anne-Marie Mièville, herself an accomplished filmmaker. He could be testy with others, even friends: Godard and Truffaut had a famous falling-out. He fulminated against Truffaut’s move towards traditional cinema (and commercial success), while Truffaut condemned Godard’s degrading treatment of women in his later films.

Anna Karina at Schipol Airport Amserdam. Photo by Joost Evers/Anefo at Wikimedia Commons

He seemed to hit a dead-end in the 1970s. As with many leftist French intellectuals, his rigid ideology didn’t attract the masses, and the efforts to make filmmaking a proletarian group enterprise didn’t interest many proletarians. He experimented with video, though he excoriated TV. Too many of the films (Vladimir et Rosa, Tout Va Bien, Letter to Jane) were propagandistic yet obscure. Like other engagé film people, such as Vanessa Redgrave, his sincere concern for the Palestinians turned into an anti-Zionism that many construed as anti-Semitic. (When he received an honorary Oscar for his life’s work in 2010, there were protests by people in and out of the film industry.) Though this way led to an artistic cul-de-sac, Godard was shrewd enough to cut his losses and find another path. And there would be many in his long middle and late career.

The 1980s marked his return to mainstream filmmaking. Films like Passion, Sauve Qui Peut and Prénom Carmen depicted the vicissitudes of relationships with middle-aged sourness. Others were twice-told tales that gave a twist to old myths and stories: Je Vous Salue Marie (his take on the Virgin Mary, among other things), Detective and King Lear.

In the tumultuous 1990s, with the end of the Cold War, construction of Europe, and wars in Yugoslavia, Godard returned to meditations on politics: Allemagne Neuf-Zero (1991, a takeoff on Rossellini’s 1945 Germany Year Zero). He also made a self-portrait, JLG/JLG: Portrait of the Artist in December. Godard saw the end of the Old World Order and analog reality with no little melancholy, associating it with his own oncoming old age.

Jean-Luc Godard by Père Ubu

In the 21st century the elegiac mood increased. Godard looked backwards at the history of cinema — at the history of history itself — in documentaries and semi-documentary fiction. The collage and essayistic techniques became more pronounced. Histoire(s) du Cinéma, a series of films, took years to complete (1988-2000). He also created a large-scale exhibit for the Pompidou Center called Voyages En Utopie. He continued, and expanded, his interest in how images from the media, official sources, and the arts, including his own images, had evolved and impacted society: Film Socialisme (2010), Le Livre de l’Image (2018). He became interested in image technologies such as 3D, contributing to the anthology film 3x3D. His own small-budget explorations (Good-bye to Language, 2014) were more impressive than what the big-money studios produced — because his had a real point, rather than just confecting CGI sense-candy for the market.

One might venture that it’s the mature Godard who will be remembered for his analytical-meditative regard upon the transition from the 20th to the 21st century. Godard was always looking ahead, but in so doing tended to kill off what came before. He even seemed to be killing off whatever he’d been in the phase before — edgy idealist, political revolutionary, ideologue, sensualist, nostalgic recluse, visionary seer. He died as he lived, but in a way they were one and the same.

Lead photo credit : Jean-Luc Godard at Berkeley, 1968 by Gary Soup at Creative Commons

More in Death of Jean-Luc Godard, Director Jean-Luc Godard, Jean-Luc Godard