The De Noailles: Art-Loving Aristocrats of Jazz Age Paris

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

They were a golden couple of the 1920s: fabulously wealthy benefactors of the arts who were famed for their dinners and balls, the modernist décor of their home in the 16th arrondissement, and their patronage of the avant-garde, and who were not afraid of a spot of scandal.

They were Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles, an unconventional couple (he was gay but their marriage endured in genuine mutual devotion) whose support launched or established the careers of many of the era’s best-known artists, writers and musicians. Despite Charles’s roots in French nobility, Marie-Laure had the more exotic background: heiress to the fortune built up by a Paris banker of German-Jewish-Quaker origin, Maurice Bischoffsheim, she counted the Marquis de Sade as a distant 3x great-grandfather. Her grandmother, Laure de Sade, was the inspiration for the Duchesse de Guermantes in Proust’s In Search of Lost Time.

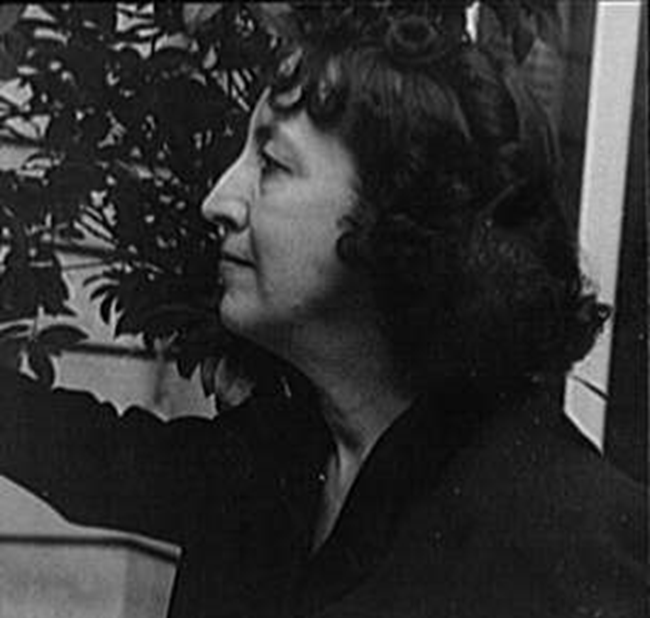

Marie-Laure de Noailles. Photo credit: Van Vechten/Wikimedia Commons

Charles was born in 1891, Marie-Laure in 1902, and they married in 1923. She was once asked, “Charles, does he like men, or women?” A question that was answered when she entered their bedroom on one occasion and found her husband in bed with his handsome gym instructor. True to the expectations of polite society, Charles never came “out” (although his sexual orientation must have been common knowledge among their friends) and he and Marie-Laure presented themselves as the perfect society couple, even to the point of having two children. Although the marriage was, sexually, a front (after the birth of their second child they slept in separate bedrooms), and they would communicate by letter using the formal vous even when both were at home, there was no pretense in the genuine affection felt between them.

Baccarat crystal chandelier inside the Hôtel de Noailles, now the Musée Baccarat. Photo credit: Nitot / Wikimedia commons

After the wedding, the couple moved into the hôtel particulier bequeathed to Marie-Laure by her grandfather Bischoffsheim at 11, Place des États Unis in the 16th arrondissement. Here, alongside the grandfather’s collection of Old Masters, they remodeled the interior in the latest modernist style. Art Deco sprang into public consciousness via the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in 1925 and the apartment was in the vanguard of this new style. Sadly, the interiors were stripped out during a later remodeling in the 1980s so all we have left are a few period photographs and two pairs of original metal doors and cement walls in what was once the salon (the house is now the Baccarat Museum).

Villa Noailles in Hyères. Photo credit: Gzen92/Wikimedia Commons

The Noailles burnished their modernist credentials further when they had a summer house built on the outskirts of Hyères in the South of France. Having failed to persuade Mies van der Rohe, or Le Corbusier, to design it for them, they turned to another fashionable architect, Robert Mallet-Stevens, who designed a quintessential Art Deco house adjacent to a medieval fortress overlooking the town. The Villa Noailles has been restored and visitors can see at first-hand the streamlined fitted bedroom furniture, the geometric skylights flooding the former salon with natural light, and the surrealist-inspired light fittings. There was a squash court, gymnasium and indoor swimming pool and the courtyard garden has been restored to its original Cubist design.

View of the Cubist Garden of the Villa de Noailles. Photo credit: SiefkinDR / Wikimedia commons

Under the tutelage of friends like Jean Cocteau the couple refined their taste. It was actually Charles who originally took the lead in supporting contemporary artists. Both their Paris apartment and their Provençal retreat boasted textiles by Raoul Dufy and Sonia Delaunay, sculptures by Brancusi and Giacometti, paintings by George Braque, Max Ernst, Paul Klee and Juan Gris. One of Charles’s first commissioned portraits of his wife was from Picasso. The couple were regularly seen at the latest exhibitions and were one of the few people in France who had bought a Mondrian. Surrealism particularly attracted them and they enthusiastically promoted writers like André Breton and Paul Eluard as well as visual artists.

View this post on Instagram

In the late 1920s the Noailles extended their patronage into cinema. A private film theater was installed at 11 Place des États Unis and they began funding a series of Surrealist films. The first of these was Cocteau’s Blood of a Poet, soon to be followed by Les Mystères du Château de Dé by Man Ray (filmed at the Villa Noailles). Then, in 1929, Luis Buñuel stayed at Hyères whilst writing L’Age d’Or with Salvador Dalì.

The film is now considered to be a Surrealist classic but it caused a storm of controversy at its premiere in 1930, in the Noailles’ private cinema. It was bad enough that Buñuel and Dalì poked fun at the Catholic hierarchy and inserted a quasi-erotic scene of toe-licking; what really made feathers fly was the final scene where revelers at an orgy based on the Marquis de Sade’s 120 Days of Sodom tumble out of a château, including the main protagonist, the Duc de Blangis, as Jesus Christ. Even the iconoclastic intellectuals in the audience (including Braque and Gertrude Stein) found this beyond acceptable and they left in silence. The Vatican placed the film on its Index of proscribed works and Charles was threatened with excommunication. He had to resign from the prestigious Jockey Club, a terrible social ostracism. The film itself was banned until 1980.

Charles and Marie-Laure reacted completely differently to the controversy. Charles retired to Hyères (and later Grasse). For the rest of his life he lived away from the public gaze devoting his time to gardening and, in time, becoming a respected authority on the subject. He continued to support modern art but discreetly. He also remained devoted to Marie-Laure even though her antics in Paris dismayed him.

The L’Age d’Or controversy seemed to liberate her from her husband’s influence. She threw off all social conventions and would speak freely about sex in front of people, and she started to take lovers. She became pregnant by the composer Igor Markevitch and after a crisis meeting with Charles and Igor she had an abortion – very much illegal in those days and scandalous as well as dangerous.

In the 1930s she pivoted again and became an active Socialist, openly supporting the Front Populaire, which formed a socialist reforming government in 1936. It has to be remembered that in the conservative circles in which Marie-Laure belonged, this was tantamount to being a Communist and she was known as the Red Viscountess.

Villa Noailles. Photo credit: Daniel Wilk / Wikimedia commons

Her behavior during the Second World War raised certain eyebrows when she had a brief affair with a Nazi officer (she thought the fact he was Austrian absolved her), although she and Charles both served in ambulance units. She was very lucky that her Jewish lineage was slight enough by Vichy standards for her to escape persecution. She continued to take lovers and it has to be said, she didn’t always choose wisely. One was a Spanish painter called Oscar Dominguez. He was quite the talented forger, knocking off copies of Marie-Laure’s Picassos and selling the originals, replacing them with his fakes.

In her 50s, Marie-Laure took up painting herself and gained a reputation as an accomplished artist, holding several successful exhibitions. By now her once-svelte figure had thickened and she had abandoned her Chanel suits for peasant-style dirndl skirts. With an insouciance only the extremely wealthy possess, she spent money with abandon, sometimes having to sell a picture to pay her debts. She was well-known for her outspokenness even to the point of outright rudeness but retained a lively interest in contemporary art and current affairs: in May 1968 she invited leaders of the student uprisings to 11 Place des États Unis to discuss politics. She feared death – almost her last words were, ”I don’t want to die!”- but it eventually came in January 1970. Charles outlived her for a further 11 years, finally passing away in 1981, still tending his flower garden at the age of 90.

Lead photo credit : The Hôtel de Noailles, private mansion of Marie-Laure de Noailles, now the Musée Baccarat. Photo credit: Celette / Wikimedia commons

REPLY