How America Saved Chanel

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

If Dallas seems an unlikely city to have revived Coco Chanel’s faltering empire in 1957, it was nevertheless in Texas where Chanel’s fortune and iconic brand were restored, thanks to Stanley Marcus, the Harvard-educated “Merchant Prince” who ran the legendary Nieman Marcus department store.

Considering Chanel’s collaboration with the Nazis in Occupied Paris, the irony is not lost that another Jewish firm was coming to her rescue. Back in 1924, it had been the immensely rich and successful Wertheimer brothers, Pierre and Paul, who had jumpstarted her business. Chanel had decided to expand her fashion house into perfumes. Chanel needed a wealthy backer, a distributor with factories and more importantly, a wide distribution network.

The Wertheimer brothers were the owners of Les Parfumeries Bourjois, the largest cosmetic and fragrance company in France.

Pierre Wertheimer at l’hippodrome de Saint-Cloud, during a race on 19 May 1924. Credit: Agence Rol/ Public domain.

Pierre was ruthless in business, a match for Chanel, and inevitably the couple fought constantly. There were threatened lawsuits and fights- Pierre called her “that bloody woman,” but sent her flowers the following day after each of their heated arguments. Yet, convinced that they were on a winner with Chanel, the Wertheimers backed her enterprise. Chanel agreed to a deal taking 10% of the profits on her perfume. It’s surprising that their business relationship lasted their entire lifetimes, particularly given Chanel’s behavior during World War II.

(The Wertheimers fled from German-occupied Paris and had made their way through Spain and Portugal to the United States. Chanel attempted to make use of the German Commission in Jewish Affairs which was responsible for seizing Jewish-owned businesses and transferring them to sympathetic, Aryan hands. These new laws gave Chanel the opportunity to dissolve her partnership with the Wertheimers and take over the company. However, the Wertheimers were one step ahead of Chanel, and had transferred their business to a non-Jewish industrialist. The mass of pre-dated documents certified by a German officer – one can imagine the bribe involved – ensured that a co-owner was in place before Chanel could make her move.)

Chanel No 5 perfume. photo credit: arz/Wikimedia Commons

Chanel, as with everything, had known exactly the scent she was looking for- it was to be utterly unique, without the heady, floral undertones women had come to expect. She spent days in the laboratories in Grasse until she was satisfied the scent was how she’d imagined it. Cost was of no importance – indeed she wanted her perfume to be the most expensive on the market. She designed the bottle, without embellishments: a simple, almost masculine square. She sprayed it in restaurants as she dined and affluent, stylish women stopped and asked what it was. Her shop in the Rue Cambon was always redolent with the scent of it. The rest is history. Chanel No 5 was born and lives to this day, as sought after as it was almost 100 years ago.

When WWII broke out, Chanel closed the doors on her business in the Rue Cambon and like thousands of others, fled Paris. Only her perfume was still for sale, and when Chanel returned to Paris shortly afterwards, she found her shop filled with German soldiers buying Chanel No 5. It had seemed to many Parisians that the German occupation would not be as feared and many were initially impressed by their civility. Chanel was not so impressed however, to find her opulent suite of rooms in the Ritz Hotel had been commandeered by the Germans, but determined to stay in the Ritz, she persuaded the management to give her two small rooms at the back of the hotel and construct a wooden staircase to a tiny bedroom in the eaves.

Coco Chanel at the Ritz Paris. Photo courtesy of the Ritz Paris

The uneasy peace in Paris was shattered by 1941. Jews were forbidden to engage in practically all business and professional businesses and internment camps were a constant threat. Resistance fighters were treated unmercifully. For every killed German, the ratio to French men shot in retaliation was often 50 to 1. There could no longer be any illusion that the occupation would be civilized and that Germany was not only the enemy of France, but for everything she stood for.

Chanel, amidst the cruelty and deprivations of her fellow Parisians, was having an affair in the Ritz with Hans Günther von Dincklage, known as Spatz. A German spy, he was a member of the Abwehr, the Nazi counter-espionage agency.

When the war ended, there would be an immediate price to pay, but the lingering taint of Chanel’s associations with the Nazis would cast a longer shadow even years later. Chanel had had many rich and influential lovers who had helped her become one of the richest women in France, but without her undoubted genius, her unlimited capacity for work, her acute business brain and total focus, these men could not take the credit for her staggering success.

But they were still unquestionably useful.

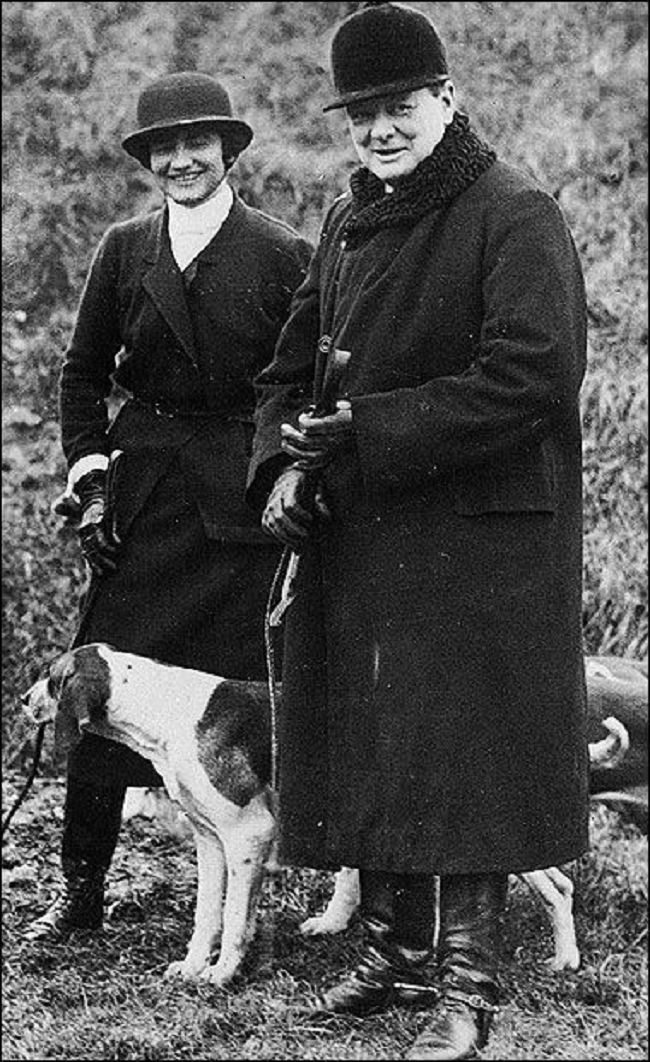

Winston Churchill and Coco Chanel. Unknown author/Wikimedia Commons

Chanel was arrested two weeks after Charles de Gaulle marched triumphantly down the Champs-Élysées. Le comité d’épuration was rounding up collaborationists, imprisoning them often without trial, but it was the women associated with Germans who were publicly humiliated. Half-dressed with their heads shaved, they were placed on platforms so the crowds could jeer at them. Chanel had not hidden her long association with Spatz; she had not suffered the hunger and cold and German brutality like other French citizens, so it appeared inevitable that the great Chanel would have the greatest of falls.

Yet Chanel was released three hours later, most likely thanks to friends in high places. Her 10-year affair with the Duke of Westminster and her friendship with Winston Churchill and the British aristocracy, including the fascist sympathizer the Duke of Windsor and Wallis Simpson, left few in doubt that Churchill had swiftly intervened after her arrest. Chanel was privy to too many embarrassing secrets, knew where the ugly bodies were buried, to be left to the mercy of an interrogation.

But Chanel knew that she had been fortunate to escape any worse consequence than a three-hour interrogation and accepted that her life and career in Paris was over. She packed up and left with Spatz into self-imposed exile in Switzerland.

Watching fashion devolve from the side-lines and years of inactivity, plus the success of her nemesis Dior, made Chanel furious. It was 1953 and she was 70 years old; to most people, including Pierre Wertheimer, she was a spent force. She returned to Paris determined to pick up where she had left off. But she still needed the financial backing of a very doubtful Wertheimer. In a wily move, Chanel leaked a letter sent to the editor of Harper’s Bazaar in New York, hinting at having an American manufacturer produce a ready-to-wear line. Wertheimer, deciding he couldn’t afford not to bankroll Chanel, agreed.

The premises in the Rue Cambon were renovated, the work room reopened and Chanel returned to her old suite in the Ritz. Chanel was back in business with a vengeance. Her 130-model collection was shown on February 5th, 1954. It was the hottest ticket in Paris, filled with the richest, most fashionable women and the most influential fashion journalists.

The show ended in a terrible silence. The ensuing headlines were excoriating. Coco Chanel was stuck in the past, Chanel was back in the 1930s, where was the innovation? Le Figaro condescendingly wrote that, “It was touching. You had the feeling you were back in 1925.” It was an astounding flop, the first in Chanel’s illustrious career. The taint of her collaboration during the war was undoubtedly still lingering.

Illustration showing three women in day outfits by “Gabrielle Channel” (sic) consisting of belted tunic jackets and full jersey skirts for March, 1917

Fortunately for Chanel, America had no such hang ups. Americans loved France and all things French, including couture. Far from finding Chanel’s creations old-fashioned, the Americans found her style youthful and liberating and more easy-going than the structured styles of Dior or Balenciaga.

And Stanley Marcus, remembering a quote from Fortune magazine in 1937 that, “Dallas people lead you to the store in the same spirit that Parisians lead you to the Louvre,” had the brilliant marketing idea of creating the annual Nieman Marcus Award for Distinguished Service in the Field of Fashion. Over the years, the publicity from these awards generated enough national attention to turn Dallas into an unlikely fashion mecca.

Stanley Marcus had always been a marketing genius and to the upwardly mobile citizens of Dallas, “the store” was a veritable institution on a par with Saks in New York. The nine-story Renaissance Revival headquarters emanated luxury and style and a blueprint for what to wear and how to live. In 1957, to celebrate the Store’s 50th anniversary, Marcus created a concept called Fortnight, a cultural extravaganza which would bring arts, food and fashion of a certain country to Dallas. France was an obvious choice, its fashion and lifestyle already popular with its wealthy clientele. Fantastic sets would turn the Dallas store into a little piece of Paris.

Coco Chanel was awarded The Nieman Marcus Award for Distinguished Service in the Field of Fashion.

Chanel suit and silk blouse with two-tone pumps, 1965. Photo credit: Mabalu / Wikimedia commons

Chanel was very aware that America had not deserted her after the war like France and Europe had. America had embraced her designs, especially her iconic Chanel suit which was worn by film stars and the likes of Jackie Kennedy. It was America she could thank for keeping her afloat and her name still relevant. (Sadly, Jackie Kennedy was wearing a pink Chanel suit, seated next to her husband, when he was assassinated in Dallas.)

Chanel flew to Dallas to a reception fit for royalty. She was wined and dined in true exuberant Texas fashion, from the white Rolls Royce picking her up from the airport to a fashion show where cattle wore Chanel’s signature fake pearls. Chanel adored every second of it, particularly the unbridled enthusiasm of Americans, and she was rewarded with great publicity that made its way back to Paris and forced fashion journals to reconsider her credibility and appreciate her designs anew. And just as suddenly Chanel was back. Her fashion house no longer floundering, her perfume sales were up and she never looked back. Her Midas touch was infallible, the Chanel bags, little black dress, and jewelry still coveted to this day.

Chanel died in 1971, aged 87, still working until the day before her death.

Her life and career inspired countless books and movies. In her lifetime, there was even a musical – but Chanel refused to see it since it starred Katherine Hepburn instead of Audrey Hepburn in the starring role (“too old!”)

Currently showing at the V&A in London, Gabrielle Coco Chanel, Fashion Manifesto advertises itself as, “the first UK exhibition dedicated to the work of French couturier Gabriel ‘Coco’ Chanel, charting the evolution of her iconic design style which continues to influence the way women dress today.” The exhibition runs until 25 February 2024.

It is already sold out.

Lead photo credit : Coco Chanel in 1920. Photo: Time / Getty - Hal Vaughan. Public Domain.

More in Chanel, Coco Chanel, Dallas, fashion, WWII