Spooky Paris Tales: From Cimetière des Innocents to the Catacombs

Just in time for Halloween, we share the spooky tale of the last and grisliest journey of millions of human remains in Paris…

In 1780, in the very heart of Paris near Les Halles, the oldest cemetery in Paris, Les Innocents, finally gave up its dead. After months of heavy rainfall, a subterranean wall between a cellar of a house and the cemetery gave way– spilling the contents of one of the many common burial pits into the cellar of the neighbouring house. It was the final death knell on a church and cemetery that had been burying Paris’s dead for as long as anyone could remember.

The church and burial grounds had started off as a small patch of burial ground called Champeaux dating from the 12th century. It was enlarged and enclosed by a three-meter wall under the reign of Phillip II. A vibrant community grew around it. The Rue St Denis and surrounding streets were bustling with houses and shops and taverns. The church was making a fortune in burial fees. (Only the poor who were buried in the common pits, were buried free.)

Complaints about the unsanitary conditions of Les Innocents were not new. In the reign of Louis XV, inspectors complained of the difficulties of conducting business in the area because of the appalling smell of bodies that had not fully decomposed. It was claimed that neighbouring houses were tainted (indeed the very breath of the occupants) by the cemetery’s stench. Candles would go out, the air was so impure.

It is difficult to imagine the magnitude of the corpses buried in Les Innocents. What had begun as a cemetery for individual sepulchres, soon became a site of mass graves. These mass graves could be up to 20 metres deep and held up to 1500 bodies.

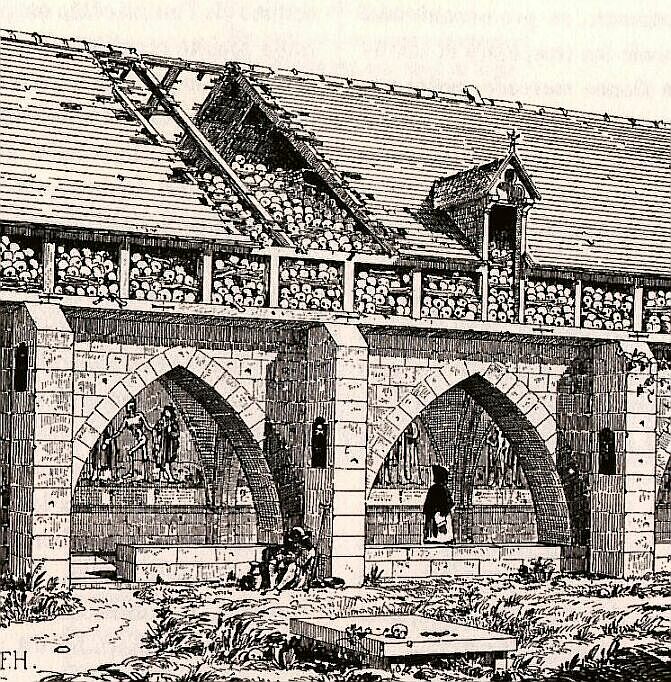

Such was the overcrowding of the mass graves, that in the 14th and 15th centuries, citizens began to construct charnels, or arched structures, along the cemetery walls to house the bones.

The church, however fearing a huge loss of revenue, fought fiercely to keep the cemetery open and despite two edicts by Louis XV to close it, it wasn’t until September 4th, 1780 that an edict finally succeeded in forbidding corpses to be buried in Les Innocents, plus all the other cemeteries in Paris. (This resulted in the construction of the Père-Lachaise, Montparnasse and Montmartre cemeteries.)

Les Innocents and its burial grounds remained closed and untouched for a further five years when finally the order came to destroy not only the cemetery but the church as well.

The awful and gruesome task was then to remove all traces of the corpses of Les Innocents.

A new resting place had to be found and old quarries– now famously known as the catacombs– were chosen near Montparnasse. The disused quarries were inspected and strengthened and the site was blessed and consecrated on April 7th, 1786.

So began the unimaginable task of clearing Les Innocents of all its remains. An estimation of 2,000,000 bodies had been buried in Les Innocents over the years, 50,000 alone in one month during the Plague. Many of the bodies had not decomposed fully and the bones had to be boiled to remove any remaining flesh. (The fat was rendered down to make soap and candles.) Fires burned day and night in an attempt to purify the air.

The bones were placed into carts and their last macabre journey began. The carts were only permitted to travel through Paris at night. They were covered in black veils and accompanied by chanting priests with incense and pitch torches crossed Pont Neuf to Porte d’Enfer. For two years, nightly processions made this same eerie journey until the cemetery and the pits and charnels had given up the last of their dead. In 1787 the order was given to destroy Les Innocents.

For a while a market stood on the spot but this too closed for the last time in 1858.

The market in the area of the Holy Innocents cemetery in 1850, engraving by Hoffbauer/ Public Domain

There is very little to mark this momentous era in the history of Paris. La Fontaine des Innocents was moved to the middle of the square in the 19th century (now named Place Joachim du Bellay) but no plaque adorns it and the surrounding establishments give no clue of Les Innocent’s past and the herculean tasks involved in the removal of its occupants.

While all traces of Les Innocents were obliterated, the catacombs were slowly becoming a tourist attraction. The site continued to receive remains from other cemeteries until 1814 when the remains of an estimated 6,000,000 corpses were lining its caverns. The catacombs now has the enviable or unenviable title of “The World’s Largest Grave.”

At first the bones were placed haphazardly, dumped really, but in 1810 Louis-Étienne François Héricart de Thury undertook the renovations of the mines and transformed the caverns into a recognizable and visitable mausoleum. Héricart organized the arrangement of the bones, stacking the skulls and femurs into sometimes elaborate patterns, that can still be seen today.

In the early 19th century, the catacombs became a fashionable place to visit, but were briefly closed in 1833 after opposition from the church to ‘exposing’ sacred bones to public display. Public demand persuaded the government to reopen the catacombs once more to the general public.

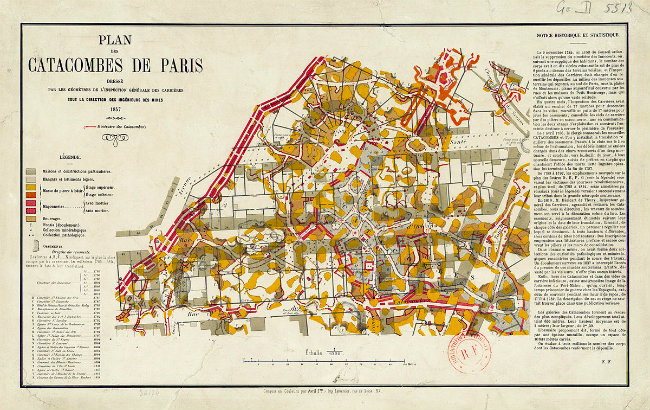

Plan of the visitable Catacombes, drawn by the Inspection Générale des Carrières in 1858/ Public Domain

The popularity of the catacombs increased unabated and although only two kilometer are permitted to be visited, another 200 miles stretch under the streets of Paris.

French resistance fighters used them to hide during WWII (although the Germans also had a base under the 6th arondissement). More recently a cinema was discovered in a cavern complete with lighting and a full sized bar. The culprits were never found.

The catacombs have been named as one of the 14 official City of Paris museums.

So maybe the story of Les Innocents still lives on.

The Catacombs can be found at 1, Avenue de Colonel Henri Roi-Tanquy, 75014. Only 200 visitors are allowed underground at a time, so there are often lines to get inside. Open from 10 am- 8 pm every day but Monday. Last ticket purchase is 7 pm.

Andrew Miller’s stunning book PURE– an historical but fictional novel of Les Innocents– is a must read for anyone interested in this era of Paris life.

Lead photo credit : Engraving depicting the Holy Innocents cemetery in Paris, around the year 1550/ Public domain

More in visiting the Paris catacombs

REPLY

REPLY