Modigliani’s Moment: “Unmasked” and Contextualized

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

We are having a “Modigliani Moment” once again, as the popular modernist Italian artist Amedeo Clemente Modigliani, born in Livorno, Italy on July 12, 1884, stars in two major exhibitions in two major museums in two major cities at the same time.

The Jewish Museum in New York organized an exhibition dedicated the artist’s early years in Paris, focusing on Dr. Paul Alexandre’s private collection of drawings and paintings amassed from 1909 to 1914. The Tate Modern in London has curated a more comprehensive retrospective of Modigliani’s paintings, drawings, and sculpture, along with a “virtual” tour of the artist’s last studio in Paris. Coincidently, the Modigliani Project recently announced its official location in midtown Manhattan.

Launched and directed by Modigliani scholar Dr. Kenneth Wayne, this impressive group specializes in the authentication of the artworks (as it is often joked, there may be more fake Modiglianis than real ones). Wayne is also working on a 2020 Modigliani centennial retrospective for the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia.

Installation view of the exhibition Modigliani Unmasked. September 15, 2017 February 4, 2018. The Jewish Museum, NY.

Whether you know the tragic story of Modigliani’s too brief life (1884-1920) or not is of little importance. You may not even remember his name. He is “that guy who paints long faces, long necks and little almond eyes.” Yes, that’s the one: Amedeo Modigliani, pronounced mow-dill-lee-on-ee (without the “dig” that most people say).

Art historians and critics might sound chummy by calling him “Modi,” his nickname, which sounds like “maudit,” the French word for “cursed one,” an apt description for this sickly fellow. However, his real friends addressed him by his full surname and his beloved mother Eugénie Garsin, a Jewish Frenchwoman from Marseille, wrote to her “Dedo,” her fourth, last and favorite child.

Comfortably middle-class when she met Amedeo’s father Flaminio Modigliani, a small businessman and friend of Eugénie’s family, she ended up supporting both her own Garsin family and her children in Livorno through private lessons and then her private school, where she taught, with her sister Laura, English and French. Naturally, her Dedo was bilingual in Italian and French.

Amedeo Modigliani, Columbine with a Fan, 1908, Black cray on paper, Private Collection [Jewish Museum]

Installation view of the exhibition Modigliani Unmasked. September 15, 2017 February 4, 2018. The Jewish Museum, NY.

From Montmartre, Modigliani found the artists living in La Ruche and then migrated with them to Montparnasse. Labelled the School of Paris, it was never an official movement, but rather a modernist sensibility inspired by Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, Cubism, and non-Western art. Among them was the colorful Fantaisiste and fellow Jewish immigrant Marc Chagall, whose work conveys a romanticized dreamy nostalgia for his Russian past. Aside from exaggeration, Modigliani’s work communicates the opposite. It exudes an almost melancholy mystery that some art historians describe as an impenetrable “mask.” The Jewish Museum tries to convince us that this is Modigliani’s Jewishness, a self-imposed shield that dealt with the anti-Semitism of the Post-Dreyfus Affair atmosphere in France.

Was Modigliani’s work a summary of this ethnic identity or a summary of his personal pain, as André Salmon indicates in his poem (below)? The two exhibitions answer this question differently, and yet neither manages to answer it definitively.

Jewish Museum installation: Modigliani’s drawings surround a Gu mask, 19th or 20th century, Wood, pigment, rope, Metropolitan Museum of Art, donated by Gertrud A. Mellon, in memory of Dr. Robert Goldwater, 1977

Modigliani: Unmasked, curated by associate curator Mason Klein, who contributed to the 2004 exhibition Modigliani: Beyond the Myth also at the Jewish Museum in New York, seems to continue a thesis he laid claim to in his catalogue essay for the first show: “In being subsumed within a monolithic reading of the period a leveling of artistic practices such as Modigliani’s only masks the discursive practice that art history has tended to resist.” (Beyond the Myth, pp. 22 – 23).

Armed with 150 drawings from Dr. Paul Alexandre’s Collection of over 450, 14 paintings, 10 sculptures, letters, notebooks and other documentation, Klein argues for an interpretation informed by Modigliani’s “common salutation… ‘Je suis Juif (I am Jewish)’.” (p. 6).

A cosmopolitan Italian, he grew up in a humanistic, secularized household, quite different from the East European Jews within his artistic circle. Klein builds his case on testimonials and inferences that speak to Modigliani’s “otherness,” an exoticism all his own: “Modigliani’s unique sense of being different—during a critical period when Europe was on the brink of war and racial difference and its associations with the Jewish question were being politicized—underlay his study of ‘types.’ For Modigliani alone, among the many Jewish émigrés in Paris, was not seen as Jewish, and thus, even among his cohort, was perhaps the sole figure who felt misread.” (Unmasked, p. 22).

This assured pronouncement smacks of more myth-making, rather than getting “beyond” it, but who cares… the show itself is magnificent, plus a rare opportunity to study artworks from a private collection.

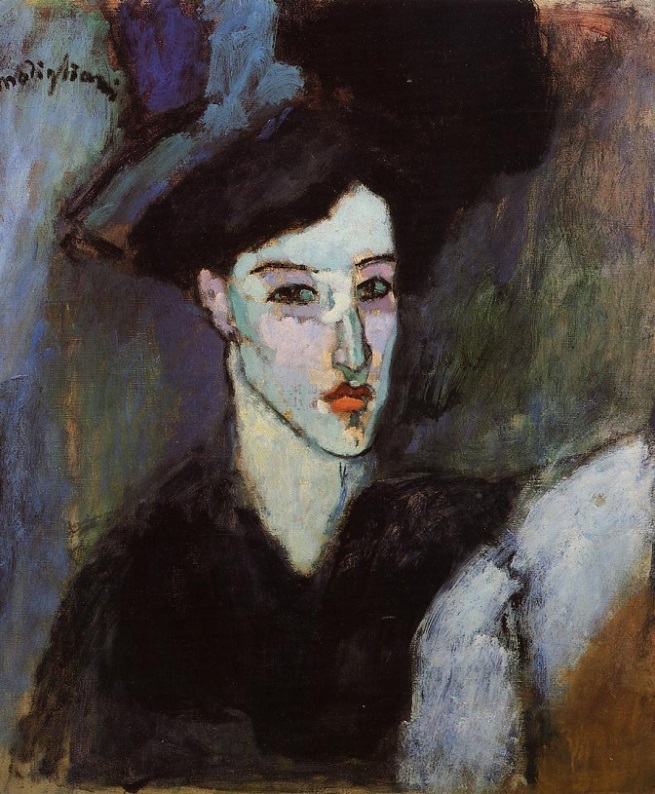

Amedeo Modigliani The Jewess, 1908 Oil on canvas, Laure Denier Collection, Paul Alexandre Family, courtesy of Richard Nathanson, London

Beautifully arranged in the elegant Warburg Mansion, which became New York’s Jewish Museum, Modigliani’s quick sketches and flat geometric studies on creamy paper loom out from the dark walls, like ghostly forms.

These drawings and Modigliani’s richly colorful paintings come alive with an undercurrent of fragile vulnerability, especially in the 1908 portraits of Modigliani’s mistress Maud Abrantes as the Nude with a Hat and The Jewess.

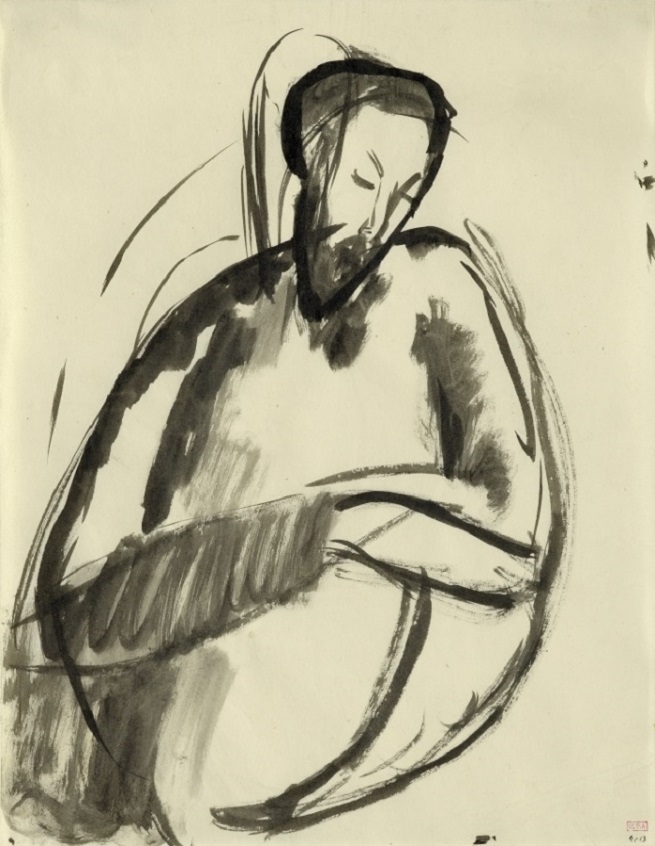

The series of 1911-1912 drawings and stone sculptures belong to his affair with the Russian poetess Ann Akhmatova, a more confident individual, captured in terms of an ancient Egyptian precision. Spare and mannered in their attenuation, they seem to blend his love of her with his favorite art of the moment. In Richard Nathanson’s essay for Unmasked, we learn that Modigliani did not draw Akhmatova from life, but rather when he was alone at home.

She wrote in her memoirs: “all around us raged Cubism, all-conquering but alien to Modigliani” (p. 151). Nathanson quoted the artist’s intent: “What I am searching for is neither the real or the unreal, but the Subconscious, the mystery of what is Instinctive in the human Race.”

With this in mind, we might view the austerity of the artist’s other-worldly elongations painted, drawn or carved in stone as a distillation of various influences, rather than mindless borrowing. He clearly rejected the Fauves’ hyper-coloristic expressionism and Cubists’ cinematic simultaneity, which were so popular among new artists during the early 20th century.

Here in this exhibition, we can feel an almost moralistic will to control every line and form for the sake of intellectual clarity. Yes, the influence of the Egyptian canon, Archaic Greek statures, and Fang masks play a part.

Also, the literal geometricity of Cubism, what we call cubisant vocabulary, comes from contact with the sculptures by Henri Laurens, Elie Nadelman, Jacob Epstein, Jacques Lipchitz, Alexandre Archipenko and Constantin Brancusi.

However, Modigliani’s carefully rendered contours seem to yearn for a new classicism of his own making, an aesthetic timeless found in the ancients he deeply admired. His insistence on stability that flew in the face of his countrymen’s dynamic Futurism also distanced him from his peers. And yet, these modernists would follow his lead after World War I, the Great Reckoning in Art, in their “Retour à l’Ordre” (Return to Order) evidenced in Amedée Ozenfant and Le Corbusier’s Purism and the clean lines of Art Deco.

Amedeo Modigliani Paul Alexandre, c. 1909 China ink on paper, 10⅝ x 8¼ in. (27 x 21 cm) Private collection, courtesy of Richard Nathanson, London Image provided by Richard Nathanson, photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates, London [Jewish Museum]

Amedeo Modigliani, Self-Portrait as Pierrot, 1915, Oil paint on canvas, 457 x 280 mm, Yale University Art Gallery, [Tate Modern]

Pierrot, Harlequin and Columbine/Pierrette often appeared in French art too, most notably in the work of his contemporary Pablo Picasso.

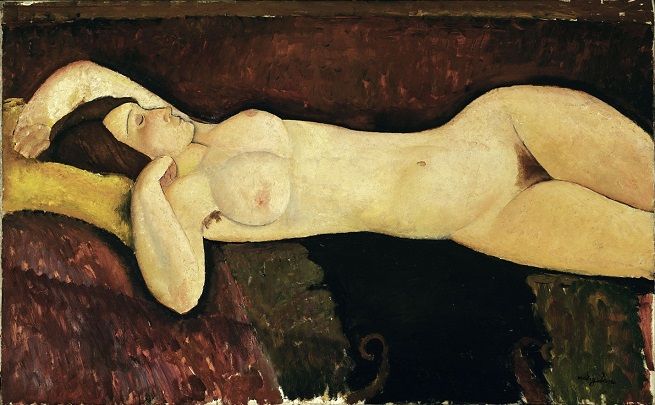

Amedeo Modigliani, Reclining Nude, 1919, Oil paint on canvas, 724 x 1165 mm, Museum of Modern Art, New York, [Tate Modern]

Mindful of this artist’s aging fan-base, curators Simonetta Fraquelli and Nancy Iveson have cooked up something special to bring in a younger crowd. This gallery features only VR googles for only a limited number of visitors at one time (up to 25 minutes each). Dubbed “The Ochre Studio,” this room offers a VR tour of Modigliani’s Montparnasse studio at 8 rue de Grande-Chaumière (now serving Modigliani meals to tourists) in order to contextualize the physical environment that gave birth to the later works of art. These digital devices usher in a whole new way of museuming. In addition to walking around and through galleries, we can also “walk” through a virtual space to gain insight into the original context of these works of art. I have not tried out the VR “Ochre Room,” but I have experienced VR at the Jewish Museum in their exhibition Pierre Chareau: Modern Architecture and Design just last year. The verisimilitude does educate the viewer, offering a better sense of the physical realities surrounding the artist as he/she creates his/her work.

Amedeo Modigliani, Jacques and Berthe Lipchitz, c. 1916, Oil on canvas, 813 x 543 mm, The Art Institute of Chicago, [Tate Modern]

Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of a Young Woman [Jeanne Hébuterne], 1918, Oil paint on cardboard, 430 x 270 mm, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen, [Tate Museum]

Amedeo Clemente Modigliani died on January 24, 1920 and was buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery three days later. Artists and writers who accompanied his body recalled that people lined the streets to pay their respects and bid him farewell. His pregnant common-law wife Jeanne Hébuterne threw herself out of a window at her parents’ home at about 3 am on January 25th. She was only 21. One child, Jeanne Modigliani, only 14 months old at the time, survived and was brought up by Modigliani’s sister Marguerite.

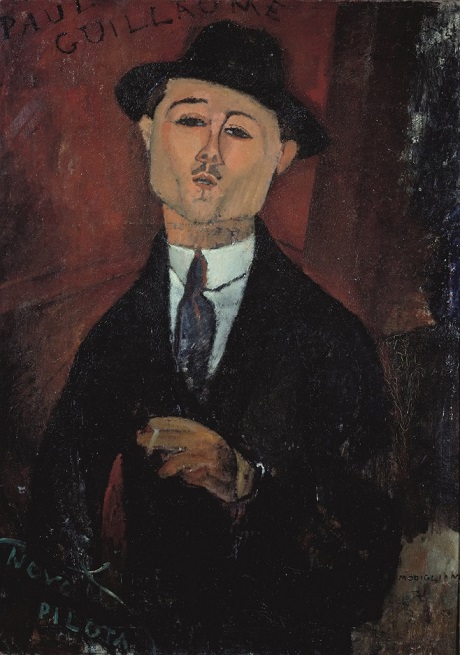

Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of Paul Guillaume, Nuovo Pilota, 1915 [Modigliani’s dealer] Oil paint on card mounted on cradled plywood, 1236 x 925 mm, Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris Collection Jean Walter et Paul Guillaume

Modigliani in his studio, photographed by Paul Guillaume c. 1915

©RMN-Grand Palais (musée de l’Orangerie) Archives Alain Buret, image Dominique Couto

Modigliani: Unmasked at the Jewish Museum closes on February 4, 2018; Modigliani at the Tate Modern closes on April 2, 2018. The Modigliani Project can be reached through its website

As we drink a glass to start the evening

You scream out a canto from PARADISE or PURGATORY

Exit, having had a good yell, and go back to your drink,

Oh! I will always hear your cries in their absence.

Martyr to a fate that has already begun.

We clinked our glasses one last time that night, with Derain.

Your album like a sky blue notebook was so heavy!

Your body bending under your fine velvet suit,

What ghostly shades bit at your flesh inside?

And this exquisite form that you always painted

Intact has followed your spirit wherever the dead go, Modigliani,

Where the dead finally live out the total worth of their pain,

The Duomo in Florence reflecting back in the waters of the Seine.

– from André Salmon’s poem Peindre, written from December 1918 to June 1920 (translated by BGN)

Lead photo credit : Image provided by PVDE/Bridgeman Images, New York

REPLY