Foujita: Artist Icon of the Roaring Twenties

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Imagine an influencer so unique that their mannequin was displayed in a Paris boutique. Imagine an artist whose looks were so radical, the police were baffled. Imagine a party animal whose stratospheric fame enabled him to have a hot car and a string of five wives. Imagine that this was 1925 and not 2025. Then we can begin to know Foujita.

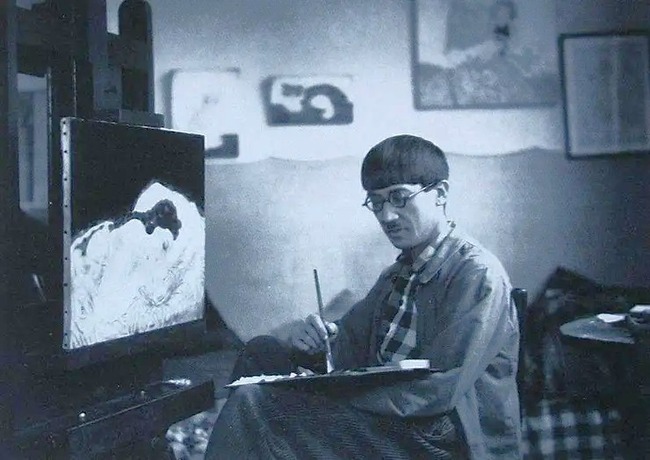

Tsugarhu Foujita was an icon of 1920s Paris. He was a wildly successful artist who created thousands of images but it’s his own self-image that’s best remembered. By 1917 this colorful Japanese expat adopted the look he kept for life: large gold earrings, a haircut with a regimentally straight fringe, and round tortoiseshell glasses.

Foujita and his mannequin. Photo: Foundation Foujita

Born into the privileged “Fujita” family in Tokyo in 1886, Tsugarhu’s father was a doctor in the Imperial army. After his mother’s death when he was four, he was coddled by his older sisters, a reason perhaps why Foujita loved to surround himself with women – and maybe the basis of his huge ego.

An early piece of Foujita’s juvenalia recently sold at Bonhams for €52,000. This jaunty chicken was one of his first paintings. He ached to become an artist but was afraid to tell his father. Foujita said his father could be “frightful to him for no real reason,” so he mailed him his wishes in a letter. His father was surprisingly supportive and bought his son his first art supplies. At 14, one of Tsugarhu’s paintings was selected to represent the work of Japanese students at the 1900 Paris Exposition. “Having my painting exhibited in Paris was the beginning of everything.” Foujita said, but it would be more than a decade before Foujita could visit the city.

Foujita’s early work, a chicken painting, which sold for €52,000. Bonhams

After playing the class clown at the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music, Foujita married his first wife Tomiko in 1911, but he never abandoned his dream to travel to Paris. He did however abandon Tomiko. At 27, with his father’s permission and a small allowance, he left for Paris, promising to return to Japan in three years. He never went back.

After 45 days at sea, Foujita went directly to Montparnasse and rented a room at the Hotel Odessa. France was still a mystery to him in 1913. The names Cezanne, Van Gogh or Gauguin meant nothing, but soon he was acquainted with the more modern painters. He visited the studios of Picasso and Diego Rivera and watched Modigliani at work. Foujita’s new friends took him to the Salon d’Automne where he was stunned by the sheer number of artworks. He started signing his name Foujita, the “o” making it slightly more French. He said, “I love Tokyo very much but being a foreigner in Paris provides me with the distance I require to understand myself.”

1914 marked the outbreak of World War I and Foujita moved to London where he designed jackets for Selfridges. He told his father he was staying indefinitely in Europe and no longer needed his money. He divorced Tomiko and returned to Paris in 1917.

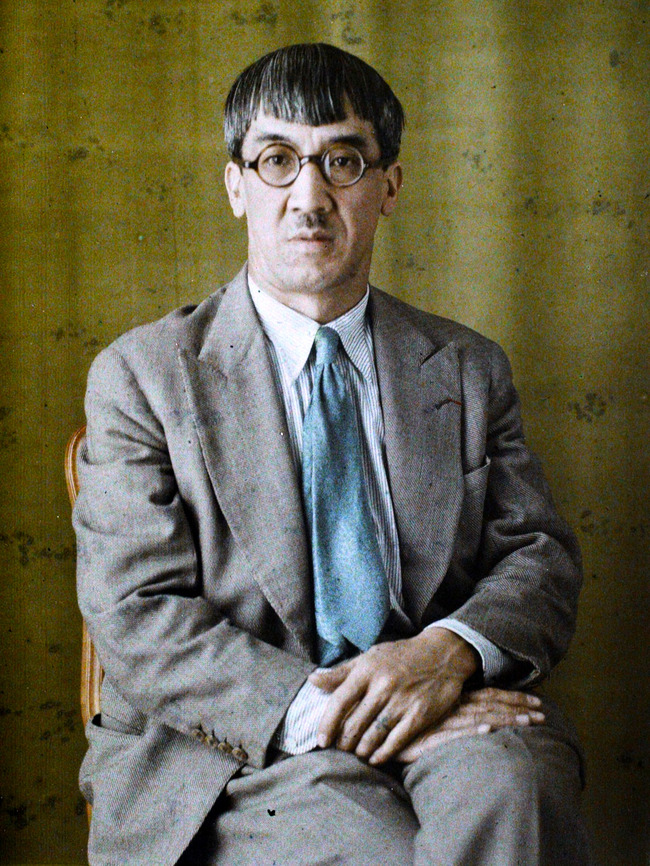

Autochrome of Tsuguharu Foujita by Georges Chevalier, 1930. Cropped, color corrected. Wikimedia Commons

Women found Foujita adorable. His homemade tunics and patterned robes gave Foujita a somewhat feminine, avant-garde appearance, but this didn’t deter them. They liked his humorous ways and charming manners. A plethora of girlfriends prepared Foujita for Paris life by teaching him how to sneak into a movie theater, how to swear, and how to pawn a watch to trade for cocaine.

Foujita moved about the Montparnasse haunts of la Coupole, le Select, and le Dome where he hung out with his wide array of artist friends. However, it was at La Rotonde, where Boulevard du Montparnasse meets Boulevard Raspail, that Foujita was most likely found. Here shortly after his return from London Foujita met his second wife.

La Rotonde brasserie. Photo: LPLT / Wikimedia commons

La Rotonde was regularly raided by police in the volatile year of 1917, checking Russian emigres and war pacifists for ID papers. They came across a small robed Japanese person with a chain around their neck and hoops hanging from each pierced ear. Never having been confronted with such an individual before, the flummoxed cop asked if Foujita was female. To prove his masculinity, Foujita said he’d already been married and soon would be again, leering toward a woman hitherto unknown. “Love at first sight.” he said.

The next day Foujita and the woman he vowed to marry walked back into La Rotonde as a couple. He’d won her over by presenting her with a simple bodice of blue which she showed off like a peacock. Foujita had sat up all night sewing his gift. Thirteen days later Foujita and Fernande Barrey were married.

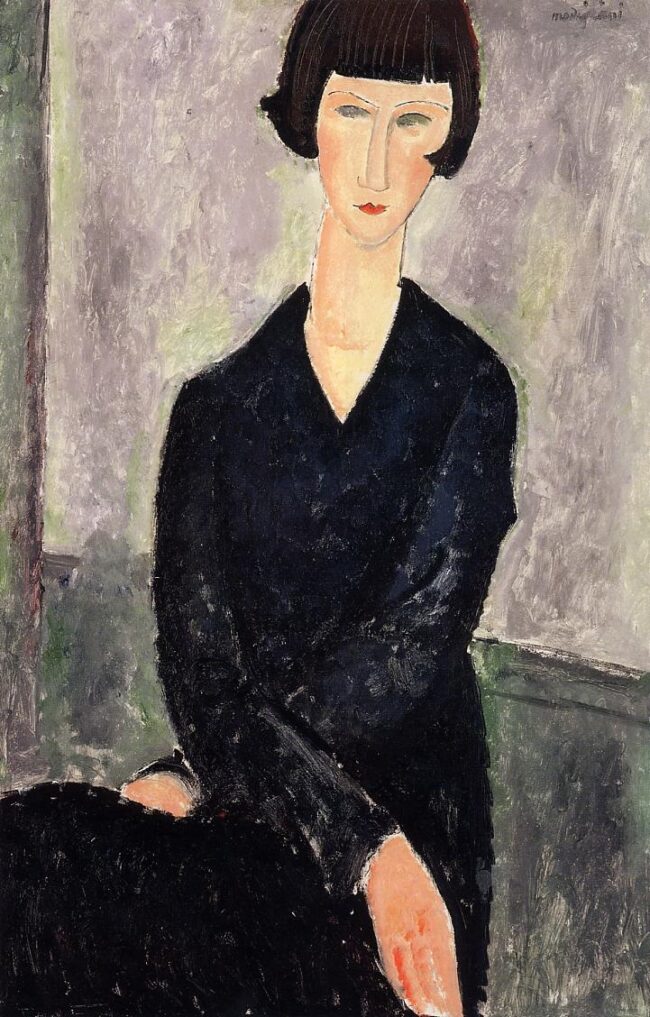

Portrait of Fernande Barrey by Amedeo Modigliani, en 1917.

The new Madame Foujita took an armload of her husband’s watercolors to the Right Bank art dealer Chéron, who returned to buy everything Foujita had at the apartment. The ever-whimsical Foujita celebrated by buying his wife a yellow canary in a cage. Chéron offered Foujita a one-man show where he sold all 110 works in one day, many to Pablo Picasso. Financially secure Foujita and Fernande rented a space – with plumbing! – on rue Delambre. Not only wealth and fame were knocking on his door, but soon a new love.

In 1922 Lucie Badoul described Foujita like this.

“He was alone, with a thick dark fringe falling onto his forehead, horn rimmed spectacles, a red and white checked cotton shirt, a little moustache in the shape of an M, a suit made of very fine British cloth.”

The 20-year-old Lucie was so taken with Foujita that after he left La Rotonde she drunkenly asked the crowded bar for the name of the Japanese artist. The waiter passed on her address to Foujita but as he didn’t respond she knocked on the door of Foujita’s studio at 5 rue Delambre. After treating her to supper at La Rotonde they retreated to a hotel for three days. The pale girl emerged with a new name, Youki, the Japanese word for snow. Still married to Fernande, his wife searched local morgues for her husband’s corpse. Foujita would make Youki his legal wife in 1929.

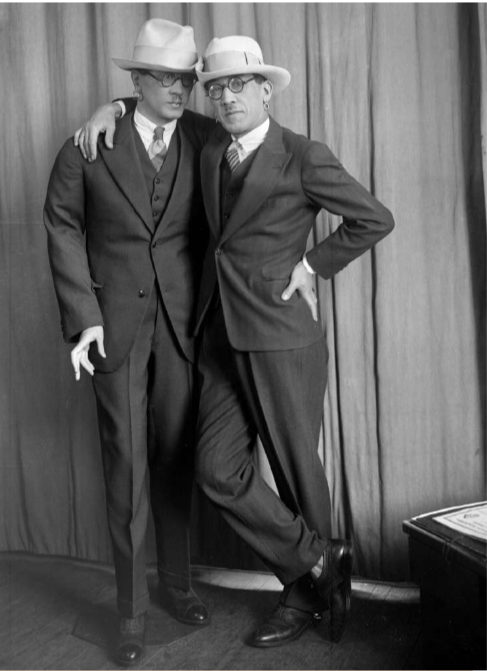

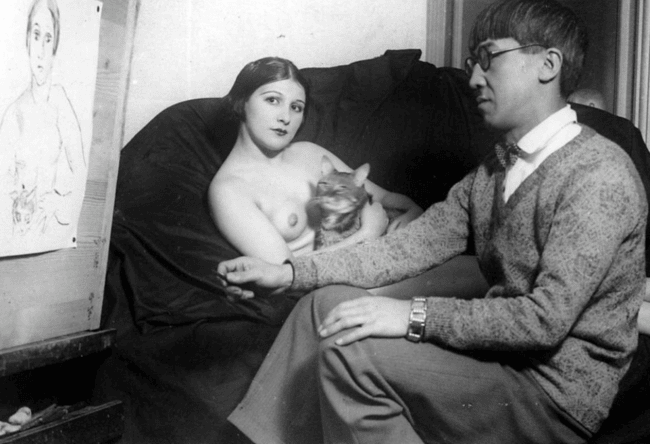

Foujita and Lucie Badou, aka Youki

By the early 1920s, Foujita found his signature style: a hybrid of Eastern and Western elements. Japanese motifs had been venerated decades before. Monet had painted his wife in a bright Japanese kimono, Toulouse-Lautrec and Van Gogh tried out the techniques seen in Japanese wood block artists like Hokusai and Hiroshige. However Foujita did not paint Mount Fuji, leaping carp or sprays of cherry blossoms. Instead he drew still lifes, landscapes, and cats galore. He simply adored cats but made a better living painting nudes – he produced an estimated 6,000 of them. What made Foujita’s work stand out was a luminescent, milky-white glaze, a secret recipe which gave his paintings a pearly finish that the West wasn’t familiar with. Foujita had a low easel and sat on the floor where he combined oil paint with touches of an Asian ink and displayed expertise with delicate Japanese brushes.

Foujita and Lucie Badou, aka Youki

In 1922 the luminous nude painting of Kiki – the Montparnasse model and cabaret performer – secured Foujita’s reputation. Foujita recalled the first time Kiki came to pose for him, “She came in slowly and timidly, her cute little finger held up to her small red mouth, swinging her behind confidently. When she took off her coat she was absolutely naked. A small handkerchief in lively colors pinned to the inside of her coat, gave the illusion of the latest dress.” However Kiki took Foujita’s place at the easel and calmly drew his portrait. She left with her drawing and within three minutes, a rich American collector bought the drawing for an outrageous price, leaving Foujita to wonder which one of them was the more lucrative artist.

Kiki then posed languishing a la Manet’s Olympia. The painting of Kiki -“Nu couché à la toile de Jouy” - was a sensation at the1922 Salon d’Automne. In Phyllis Birnbaum’s book Glory in a Line, Foujita is quoted saying, “In the morning all the newspapers talked about it. At noon the Minister congratulated me. In the evening, for the sum of 8,000 francs it was sold to a famous collector.” Foujita shared the proceeds with Kiki and they remained good friends.

Léonard Foujita, Nu couché à la toile de Jouy, 1922. Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris

Foujita’s paintings were bought by galleries throughout Europe, London, New York and Chicago. In a year Foujita could produce about 200 artworks. Disciplined when it came to art. Foujita was a non-drinker which kept him clear-headed for his next day’s work. He would often have finished his first painting of the day when friends staggered to their coffee pots. When friends questioned his even-temperedness, he claimed to have inherited this sensibility from his samurai forebears.

Foujita and Kiki (with the portrait of Kiki painted by Foujita in the background), detail from the photo taken by Marc Vaux, circa 1920.

Despite this Zen-like philosophy, Foujita was an extrovert who gave importance to his public image. Being sober didn’t stop him outdoing the high jinx of his intoxicated colleagues. He took pleasure in dressing up in crazy costumes, sometimes in drag, for the numerous masquerades held in the Montparnasse neighborhood. Known to friends as “Fou Fou,” from the syllable of his name that translated as “Crazy Crazy,” he hosted lavish parties. Youki once had to dissuade him from wearing his Legion d’Honneur medal (received in 1925) on his costume of a caveman in a loincloth. The press loved him and his antics were followed in gossip columns, where owlish caricatures made him instantly recognizable. He fashioned a life-sized doll of himself and a Paris department store used a mannequin of Foujita in their window. Ahead of his time he had a watch tattooed on his wrist and a ring on his finger.

Kiki de Montparnasse and Tsuguharu Foujita, Paris, 1926, by Iwata Nakayama. Public domain

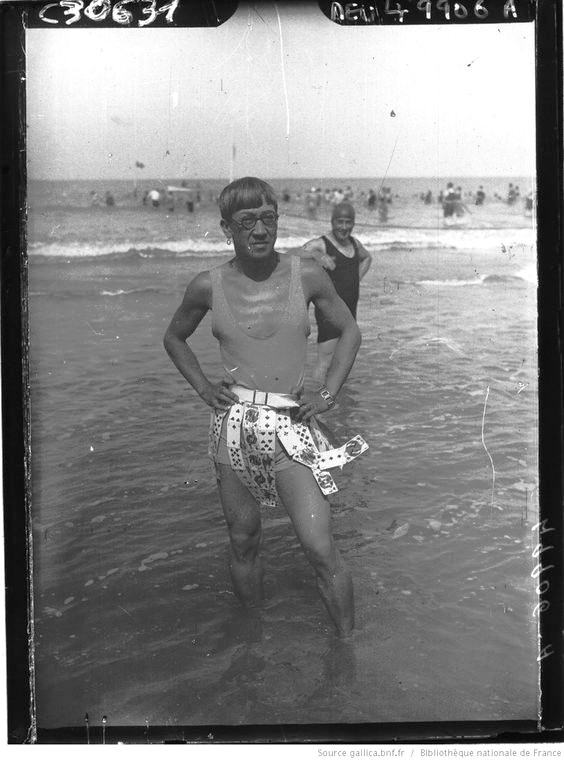

Foujita surprised Youki on her 21st birthday with a large yellow car complete with, a chauffeur, and a hood ornament cast by Rodin. In it they traveled to Saint Tropez, Cannes, Deauville where Foujita rode a children’s bicycle for the cameras and wore a rudimentary skirt strung from playing cards.

Foujita and Youki rented a large house at 3 square de Montsouris, and decorated the interior with furnishings bought from mystery writer Georges Simenon. For the inauguration of their new home, Foujita called on Alexander Calder, known for his mechanical installations and mobiles, to put on a a makeshift circus on Foujita’s third floor. Peanut-munching guests sat on a ring of wooden crates watching Calder’s “humpty dumpty” mechanized circus on a miniature scale.

Square de Montsouris. Photo: Hypersite / Wikimedia commons

Although Foujita’s art made him financially successful, he wasn’t one to save his francs. In 1929 Foujita found that he owed an astronomical amount in back taxes. Despite Youki helping raise money through these tough times, Foujita fell in love with someone else – an exotic dancer called Madeleine (Mady) Lequeux. Foujita fled to Latin America with his new lover, and soon-to-be fourth wife. Youki sold the house and married the surrealist poet Robert Desnos.

Foujita spent three successful years touring South America, Mexico and the Southern US before returning to Japan in 1933. Cooperating with the Japanese regime, public opinion soured against Foujita when he became an official war artist during World War II. He defended his reputation saying that he, like all artists, was a natural pacifist. In 1936, when Mady succumbed to a stroke in Tokyo, Foujita had already moved on; he’d met the much younger Kimiyo the year before. Their relationship would prove to be his longest lasting and in 1950, Foujita and Kimiyo left Japan permanently for France.

Foujita at the beach. Gallica/BnF

In 1955, Foujita became a French citizen. He converted to Catholicism in 1959, and at his baptism at Reims Cathedral he was christened Léonard. His later years were spent creating theatrical costumes, painting street scenes, and strange solemn doll-headed girls. In Reims, old Foujita found the energy to paint religious frescoes in a chapel of his own device, commonly known as the Foujita Chapel. He died in 1968 not long after the chapel officially opened in Reims and his remains are in the cemetery outside.

Foujita’s art is still appreciated by collectors. Recently his cats and nudes have been commanding over a million euros. His 1949 “La Fete d’Anniversaire” sold in 2018 for more than 8 million euros. Imagine that!

Note: The Maison-Atelier Foujita, located in the village of Villiers-le-Bacle, 50k south of Paris, is temporarily closed.

Portrait of Foujita. Unknown photographer

Lead photo credit : Foujita in his studio. Photo: Jean Agélou/ Public domain

More in Foujita, Montparnasse

REPLY

REPLY