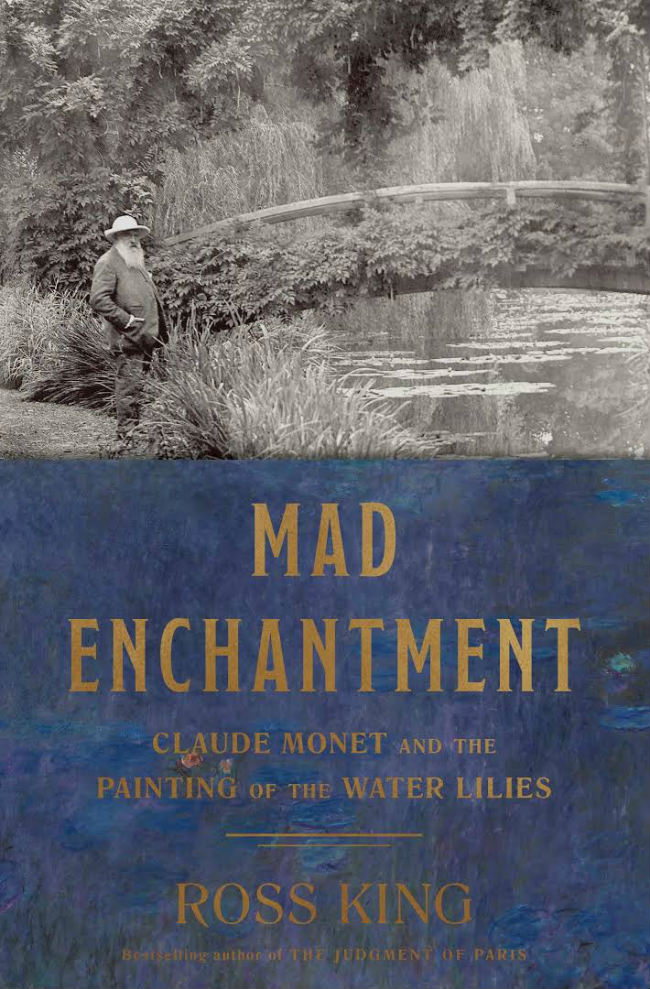

Book Reviews: Mad Enchantment, Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

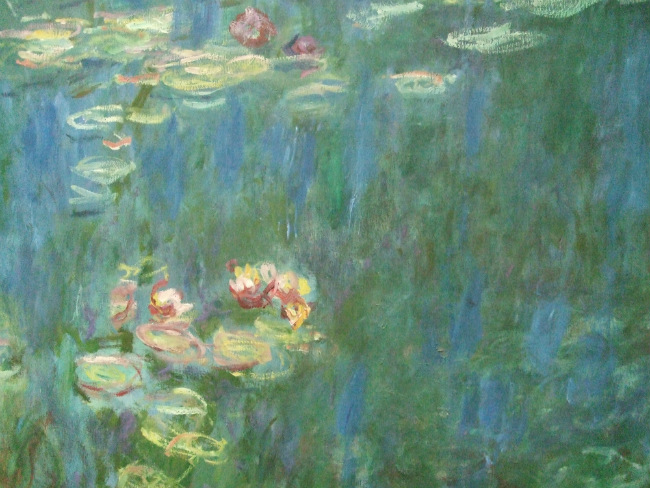

close up of Monet’s water lilies. Photo: Hazel Smith

At this time of year drowsy purple asters or a clutch of steadfast zinnias can evoke memories of my autumn trip to Giverny, home of the world’s most prolific Impressionist painter, Claude Monet. As a student of art history and a visitor to Monet’s historic home and gardens, I thought I had a good grasp on who the painter was, but I didn’t know the whole picture. Ross King, the multiple award-winning writer and author of Mad Enchantment, Claude Monet and the painting of The Water Lilies, reinforces the myth of Monet but introduces us to the man few know. King cleverly writes Mad Enchantment to read not like an artist’s biography, but a chronicle of time and place. He weaves together the threads of friendship, war, creation, and death to describe the final chapter in the life of the Claude Monet. King explains how Monet’s Nymphéas eventually wound up at Paris’s Musée de l’Orangerie, but he also follows the close friendship between Georges Clémenceau and Monet, an allegiance that lasted 50 years which was almost destroyed by Monet’s inability to surrender his Grande Décoration to the French people.

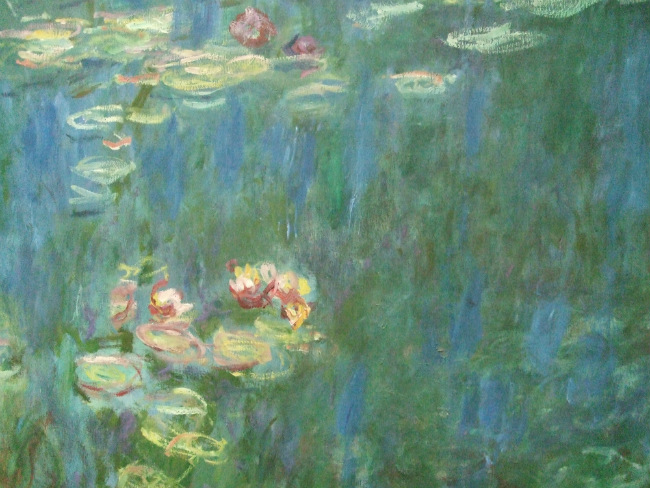

Giverny, the small village northwest of Paris, was an earthly paradise when Monet purchased his famous pink house there in 1890. Known as “the painter of happiness,” a contented Monet found fame within his own lifetime and was the highest paid artist of the day. However, everything fell apart in 1911, when his wife died. Monet was inconsolable and, as he also began to lose his sight to cataracts, he stopped painting.

The only person who could persuade Monet back to work was longtime friend and former French President Georges Clémenceau. When Monet felt able to undertake great things again, Clémenceau urged him to finish the ambitious “flowery aquarium” of canvases known as the Grande Décoration, based on the water lilies found at Giverny. The scale of this project was immense. He painted an atmosphere of infinite blues, greens and mauves that was dreamily eternal. Monet would work on these paintings throughout the war years and the rest of his life.

Water lilies in Monet’s garden in Giverny. Photo: Hazel Smith

Georges Clémenceau and Monet had known each other since they were wild young men. Clémenceau, after his first term as President, still seemed strong and unconquerable, and was widely known by the French people by his nickname “The Tiger.” Monet by contrast was prone to petulance and frustration. Clémenceau called Monet an assortment of personal nicknames: “old lunatic” “poor old crustacean” and “frightful old hedgehog.” By 1914 when King’s story takes hold, these once enfants terribles had grown into grand old beasts. Ross King movingly chronicles this friendship in a France gripped in war.

Monet was first enchanted by the water lily hybrids seen at the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris. In hindsight it’s odd to think that Monet ordered just six water lilies, two pink and four yellow, as a motif to paint from his garden, when today his Nymphéas have such an important place in the register of fine art. Ross King describes how the painting of the water lilies pulled Monet out of his initial depression yet caused him great anguish. Monet, whose works were known by Proust as the “great antidepressant” suffered crisis after crisis of confidence.

Monet’s paintings displayed at the musée de l’Orangerie. Photo: Hazel Smith

“This satanic painting tortures me,” he earlier wrote to his friend Berthe Morisot. Harmonizing colors, tones and shadows on canvases so large caused him difficulties. Plagued by his diminishing vision, Monet was known to madly destroy his canvases. Monet was raging against the dying of the light, both literally and metaphorically.

Mad Enchantment gives the reader a personal, albeit privileged, view of life during World War I. The war raged within earshot of Monet at Giverny. Although it seemed imprudent to be working on the Grande Décoration during a time of suffering, Monet soldiered on, painting his lilies before his sight went altogether. After pressure from politicians, friends and Clémenceau, Monet made a decision the day after the 1918 Armistice to award the State with his series of giant water lily canvases as a tribute to a victorious France. The entire series of paintings would be kept together on the walls of a purpose-built space where visitors could seek quiet contemplation. However, the completion of the task would take years.

American, Russian and Japanese millionaires tried to wrest Monet’s water lilies from his iron grip. He did not want to part with them, patriotically believing the series should stay within France. In fact, Monet soon found ways of postponing the delivery of his great composition altogether. Despite the repeated drama surrounding his cataract treatments, Monet’s wavering about the date put a great strain on his friendship with Clémenceau. Then in January of 1925 Monet drastically retracted his donation. He decided he did not want to relinquish his canvases while he still drew breath – otherwise his life’s work would be finished. The water lily project which had saved Monet madly consumed him. Clémenceau wrote “If he does not alter indecision, I shall never see him again.”

Monet’s paintings at the musée de l’Orangerie. Photo: Hazel Smith

Ross King is an avid researcher (his book contains 43 pages of notes) and a fluent and compelling writer. His 2006 book The Judgment of Paris is never far from my bedside. King avoids all the academic pitfalls of being dry and pedantic and is instead a joy to read. I recently had the chance to catch Ross King at a salon-like setting. When his interviewer declined to show, King carried on with his presentation, not missing a beat, and left the crowd wanting more. Thanks to King’s abundant research and easy style, Mad Enchantment will be a touchstone for art lovers, students and the merely curious for years to come.

King quotes that Monet’s Nymphéas captures the “ephemeral and the eternal, magnitude and minutiae.” The nearly 100 linear meters of murals lining the oval rooms of l’Orangerie invoke “oohs” and “aahs” from the visitors. When personally faced the “luminous abyss” of glaucous blues and greens, they take up one hundred percent of my sense of sight. Should I sink or should I swim? The voice of the guard returns me to reality. And I step back.

Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies. By Ross King. Bond Street Books, 2016. In Paris, see Monet’s water lilies at the Musée de l’Orangerie, open every day except Tuesday from 9 am- 6 pm.

Related articles:

On the Trail of Claude Monet in Paris

The Flowering Calendar of Claude Monet’s Garden

Lead photo credit : close up of Monet's water lilies. Photo: Hazel Smith

REPLY