Jean Rhys: The Forgotten Novelist of 1920s Paris

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

The 30-something woman sits at the back of the Montparnasse café. She is neatly dressed but her coat and hat are shabby and were fashionable several seasons ago. She knows, by face and name, most of the noisy English and American expatriates on the terrace. But despite being English herself, she is not part of their coterie. And anyway, sitting indoors is cheaper. She ekes out a café crème and a cheap brandy chaser, and waits.

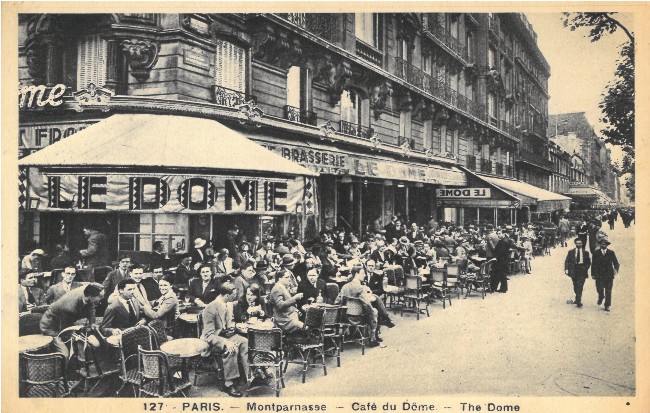

Such is the kind of woman so poignantly portrayed by Jean Rhys in the handful of novels she wrote in the 1920s while living in Paris, and the 1930s. The novels are heavily autobiographical. Like her heroines, Rhys lived on the fringes of the glamorous expat and artistic circles of Montparnasse. While other books about the place and period concentrate on the glittering milieu of artists, novelists and poets, Rhys used her firsthand knowledge to write about the women on the margins: models, shopgirls, women with no regular income who relied on their looks to be kept afloat by wealthier men. Single women living in drab hotel rooms. No one captured that subculture better.

Le Dôme Café Montparnasse in the 20th century. Public domain

Jean Rhys was born Ella Gwendoline Rees Williams in Dominica, in the West Indies. Her date of birth is inexact: it was probably 1890, but Jean claimed it was 1894. At any rate, Ella was sent to school in England at the age of 16 and the pattern of being an outsider was set. She spoke with a heavy Creole accent and knew nothing about English customs or behavior, which immediately set her up to be bullied. After an unhappy two years she enrolled in drama school.

Ella was pretty and averagely talented but although she worked regularly on the stage she never rose above the chorus line and during the First World War worked for a year in the Ministry of Pensions. During this time she met, and married, a dashing Dutch-Belgian called Jean Lenglet.

Lenglet was the classic charmer-cum-conman; he was also a bigamist who led Ella on a decade of rackety life in Paris and Vienna. The first spell in Paris, between 1919-1920, was undistinguished apart from the birth of a baby son who died after a few weeks. But their return in 1922 (Lenglet was on the run for suspected embezzlement) proved to be a turning point for Ella. She was fortunate to meet the English author Ford Madox Ford, then at the height of his popularity. Ford took her under his wing, encouraged her to write, persuaded her to change her name to Jean Rhys, and started publishing her stories in his magazine Transatlantic Review. Through him she became acquainted, at a distance, with the Lost Generation of expat writers such as Ernest Hemingway and their hangers-on, who had colonized the café terraces of Montparnasse.

Ford Madox Ford circa 1905. Wikimedia Commons

Jean was someone who simply found life difficult. She had no grasp of practicalities and tended to let events sway her this way and that without really taking control. Through Lenglet’s ducking and diving, her domestic life was disorganized at best and sometimes downright bordering on criminality. She never really belonged anywhere. Her heroines are the same: lower middle class and therefore despised from above and below, educated to a very average level, and lacking any discernible talent that might have led to a successful career. They are alone, literally, and also cut off from their families and home. Perpetual outsiders, often living on the fringes of a criminal underworld. They experience failed marriages, mental breakdown, infant mortality and the painful realization that their beauty, their meal ticket, is fading. All of these featured in Jean’s life at one time or another.

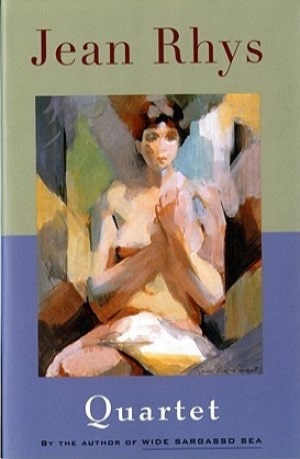

At Ford’s persuasion, Jean wrote her first novel fictionalizing the fraught three-way relationship between herself, Ford and Ford’s wife Stella Bowen. By now Lenglet had been caught and imprisoned and this, too, appears in the novel. Jean had no filter: her life was her work and she portrays her fictional self unsparingly. The novel was published in 1928 under the title Postures (later changed to Quartet).

It received mostly positive reviews in the English press and Jean was hailed as a promising new talent. Three more novels followed: After Leaving Mr. Mackenzie was published in 1931, Voyage in the Dark in 1934 and Good Morning, Midnight in 1939. Her innovative style firmly established her as a Modernist. Jean had moved back to England in 1928 but she continued to mine her Parisian experiences, and autobiographical elements fill her work.

And then… nothing. The Second World War arrived and Jean Rhys, bruised by the poor reviews of Good Morning, Midnight, disappeared into the English countryside. Nothing was heard of her for 10 years. When the BBC wanted to broadcast an adaptation of Good Morning, Midnight in 1950, its writer, Selma vas Dias, had to place an advertisement in the newspapers asking anyone who knew Jean’s whereabouts to come forward. Both of Jean’s former publishers were sure she was dead.

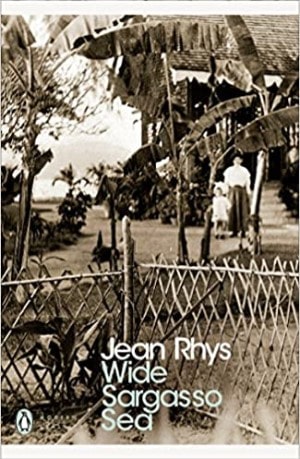

The adaptation wasn’t broadcast for another seven years but it was a rebirth, of sorts, for Jean. She was befriended by a new generation of writers and started her most famous novel, Wide Sargasso Sea. These days we would call it a “prequel”: the backstory of Mr Rochester’s first wife, under Jean’s pen now a Creole from the West Indies, who was the “madwoman in the attic” of Jane Eyre.

In her personal life, Jean was a wreck. A life of heavy drinking had degenerated into alcoholism and many times she was brought before local magistrates for drunken and antisocial behaviour. Her third husband Max Hamer was another chancer who also spent time in prison and then had to be nursed by Jean after a stroke. Living in the country, she was physically isolated, in poor health, and prone to anger, depression and paranoia. Despite all that, Jean always liked to dress well and could be sociable and entertaining when friends took her off to London.

The publication of Wide Sargasso Sea in 1966 finally brought Jean real literary recognition. Her novels were republished and her short stories appeared in new collections; in truth she had never stopped writing. Befriended by Sonia Orwell (George Orwell’s widow), she was adopted by a younger generation who recognized that Jean’s merging of personal experience and fiction had enabled her to write about women with insight, empathy and sensitivity, even though the subject matter had been controversial. But when she finally won a major British literary award in 1966, she said sadly it “was too late, too late.”

Jean Rhys passed away in 1979 at the age of 89. Her Paris novels are not, to be truthful, cheerful tales. But despite the underlying melancholy they are painfully honest about the twilight life so many women led in the interwar years. As an antidote to the glamorous mythmaking attributed to the Lost Generation, they are hard to beat and vividly bring to life the flipside of living in Paris at that time.

Plaque for Jean Rhys erected in 2012 by English Heritage from Wikimedia Commons

Lead photo credit : Jean Rhys (left, in hat) with Mollie Stoner, Velthams, 1970s from Wikimedia Commons

More in 1920s Novelist, Jean Rhys, Lost Generation, Women who shaped Paris

REPLY