Suzanne: Leaps of Fate

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

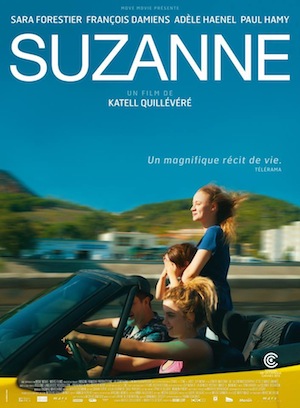

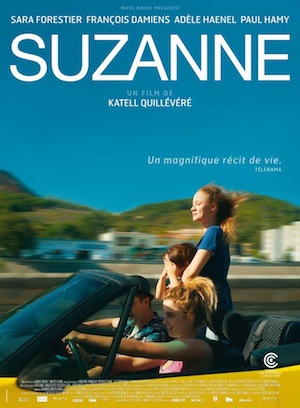

Suzanne was one of 2013’s best films but also one of the most overlooked (including by this reviewer). Winning the best supporting actress César brought it some attention, but it’s playing in one solitary venue, the Entrepôt, a wonderful cultural space in Paris’ 14th arrondissement (currently in one time slot on one day of the week). The beauty of cinema in Paris is having places like the Entrepôt where one can catch films neglected by the multiplexes.

Suzanne was one of 2013’s best films but also one of the most overlooked (including by this reviewer). Winning the best supporting actress César brought it some attention, but it’s playing in one solitary venue, the Entrepôt, a wonderful cultural space in Paris’ 14th arrondissement (currently in one time slot on one day of the week). The beauty of cinema in Paris is having places like the Entrepôt where one can catch films neglected by the multiplexes.

Suzanne is only the second feature directed by Katell Quillévéré, a 34-year-old who’s also a screenwriter and costume designer. It’s remarkably assured and free of cliché (except for the closing credits, which run to the tune of Leonard Cohen’s song “Suzanne”). The Suzanne of the film is a young woman who has everything going against her. She comes from a working-poor family in a run-down town, her mother died young, and she gets mixed up with a shady boyfriend. The subject might seem to be a conventional French social drama, flirting with the poverty-wallowing that the French call misérabilisme. The film is nothing of the sort.

From the opening scenes, of a dance show put on by little schoolgirls followed by a graveside picnic, we know we are in the hands of a budding master. Everything seems just right, even when it’s a bit odd. These early sequences take place in the early ‘80s, and all the period décor is spot on. The saturated visuals, resembling 16mm, evoke old-fashioned home-movies, the poignant dreams and emotions of family memory.

The movie then jumps ahead a few years. Quillévéré handles this elliptically but in a way that is entirely believable, unlike most films which take in long snatches of time. The father is aged with different hair-styles and life situations, the girls played by different actresses at first. The film shifts time-frames several times, and after the sisters reach adulthood, the weight of these changes falls on the actresses playing them, Sara Forestier (as Suzanne) and Adèle Haenel (as Maria), who do a beautiful job.

The movie then jumps ahead a few years. Quillévéré handles this elliptically but in a way that is entirely believable, unlike most films which take in long snatches of time. The father is aged with different hair-styles and life situations, the girls played by different actresses at first. The film shifts time-frames several times, and after the sisters reach adulthood, the weight of these changes falls on the actresses playing them, Sara Forestier (as Suzanne) and Adèle Haenel (as Maria), who do a beautiful job.

Suzanne and her sister seem happy despite the early loss of their mother, the absences of their trucker father, their general want. They enjoy family life, like boys, have a good time in the bucolic southwest of France. But hardship grabs hold of Maria, who finds employment doing deadening assembly-line work and seeks release in dance clubs. Suzanne’s out is a young man named Julien. Good-looking in a lunkish way and happy-go-lucky, Julien provides something more than a good time or even love: genuine passion. When she follows him to the north, life will take a not-so-simple twist of fate.

It seems that Suzanne is on a downward spiral as her boyfriend leads her away from her family and onto the wrong side of the law. But her twists of fate always have unexpected ramifications. Her child by an earlier fling is placed in a foster family, leaving Suzanne bereft, but also enabling her to have a more normal relationship with him. When she winds up in criminal proceedings, her public defender (played with great empathetic warmth by Corinne Masiero), turns into a surrogate mother of sorts.

It seems that Suzanne is on a downward spiral as her boyfriend leads her away from her family and onto the wrong side of the law. But her twists of fate always have unexpected ramifications. Her child by an earlier fling is placed in a foster family, leaving Suzanne bereft, but also enabling her to have a more normal relationship with him. When she winds up in criminal proceedings, her public defender (played with great empathetic warmth by Corinne Masiero), turns into a surrogate mother of sorts.

All these buffetings leave their mark on Suzanne: she ages and metamorphoses shockingly before our eyes. But Sara Forestier not only expresses the hardening in Suzanne, but also her tenacity and feeling. Quillévéré shoots the Dickensian twists and turns not melodramatically, realistically or lyrically, but in a poetic-prose style, reminiscent of some of Bob Dylan’s songs (the Dylan of “Tangled Up in Blue”).

Suzanne is a near-perfect collaboration between Katell Quillévéré’s humane, imaginative direction and writing, and the stellar performance of the cast. Adèle Haenel clearly deserved her César. As Maria, she is a kind of Sister Courage, stoically bearing her own lot and that of Suzanne. François Damiens as Nicolas, the father, is imperfect, sometimes angry, sometimes bewildered at the turn of events, but always loving. Paul Hamy as Suzanne’s boyfriend authentically echoes the bonhomie and desperation of those genial hoods one sees (and generally avoids) hanging out on seedy streets.

Suzanne is a near-perfect collaboration between Katell Quillévéré’s humane, imaginative direction and writing, and the stellar performance of the cast. Adèle Haenel clearly deserved her César. As Maria, she is a kind of Sister Courage, stoically bearing her own lot and that of Suzanne. François Damiens as Nicolas, the father, is imperfect, sometimes angry, sometimes bewildered at the turn of events, but always loving. Paul Hamy as Suzanne’s boyfriend authentically echoes the bonhomie and desperation of those genial hoods one sees (and generally avoids) hanging out on seedy streets.

In the end, after recounting all sorts of tribulations, Suzanne is a life-affirming film. One would like to say one leaves it with a warm feeling. But it isn’t really a feel-good movie. The heroine (and the viewer) may have earned the right to affirmation, but the harrowing costs aren’t about to be refunded. So one leaves thinking about the twists one own life has taken, and those which are to come. But a twist one doesn’t regret is having seen this fine movie.

Production: Move Movie

Distribution: Mars Distribution

More in film review, Paris film, Paris films, Suzanne