Interview with Meg Bortin on Life, Food and Journalism

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

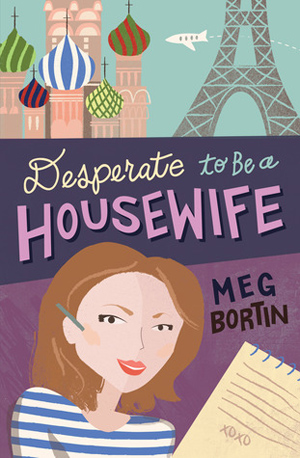

For many years Meg Bortin was a reporter and top editor at the International Herald Tribune (now the International New York Times). Her ebullient personality leaves one with the impression that they don’t make ‘em like they used to. After a rollicking career in journalism, Bortin cheerfully embraced other challenges. She wrote a book in which she tried to make sense of all that happened to her. She adopted, as a single woman, a baby girl from Mali. She then turned her attention to cooking and the new media, running a blog about French cuisine. Bortin now dreams about writing a cookbook. Her memoir, Desperate to be a Housewife, details one woman’s evolution (with plenty of hair-raising adventure) amidst historical upheaval in Europe. It would make a great movie—too bad Barbara Stanwyck isn’t around to play the lead.

For many years Meg Bortin was a reporter and top editor at the International Herald Tribune (now the International New York Times). Her ebullient personality leaves one with the impression that they don’t make ‘em like they used to. After a rollicking career in journalism, Bortin cheerfully embraced other challenges. She wrote a book in which she tried to make sense of all that happened to her. She adopted, as a single woman, a baby girl from Mali. She then turned her attention to cooking and the new media, running a blog about French cuisine. Bortin now dreams about writing a cookbook. Her memoir, Desperate to be a Housewife, details one woman’s evolution (with plenty of hair-raising adventure) amidst historical upheaval in Europe. It would make a great movie—too bad Barbara Stanwyck isn’t around to play the lead.

How did you wind up in France and Russia?

I came to France as a student during the Vietnam War years, met a man and had the good fortune of becoming a journalist. One thing led to another and I’ve now been here for most of the past 40 years. As for Russia, that was a bit of a fluke. My great-grandmother, whom I adored, was from Russia, and in her apartment she had newspapers with funny letters. Trying to connect with my roots, I studied Russian at university. Reuters saw Russian on my CV and sent me to Moscow. Only much later did I learn that those newspapers were actually in Yiddish.

What was the best thing about working as a reporter in Paris? What was the biggest challenge?

The best thing for me was access to interesting people. In my first year on The Paris Metro, we did a special issue on the tenth anniversary of the uprising of May ’68 for which I was asked to interview some of the leaders – intellectuals, artists, journalists. Later I interviewed France’s first minister for women’s rights, flew to New York with President Mitterrand, toured a Chagall retrospective with Marc Chagall himself. The biggest challenge was not falling into clichés about the French.

Is there a particular failing by journalists in covering France?

The complicity between journalists and politicians is often mentioned by critics of the French press. An example is Francois Mitterrand’s out-of-wedlock daughter Mazarine, whose existence was known by the presidential press corps for years before it was reported. But even the best journalists in other countries are often guilty of similar complicity, if only in the choice of the stories they cover.

Your book vividly describes your experiences in Russia at the time of the fall of communism. Do you think reporting there now would be any different?

Yes, very different. During the Gorbachev era journalists faced restrictions – we were listened to, watched and followed – but we had the exciting job of reporting on the opening up of a closed society. Now, under Vladimir Putin, things are moving in the opposite direction. Russia is increasingly undemocratic. Journalists are being jailed – and sometimes killed. The Internet is censored like the papers in the Communist era. It’s very depressing.

Could you have imagined the rise of someone like Vladimir Putin?

Yes. In fact I predicted it. When I returned to Russia in the 1990s I worked on an investigative journalism project looking into the disappearance of the money of the Soviet Communist Party after it collapsed in 1991. Clues indicated that the money was hidden abroad and that a ‘sleeper’ – a trustworthy but not prominent figure – would be chosen to return to the helm of a resurrected empire when the time was right. Putin fits that description, especially with his KGB background.

What advice would you give to a budding journalist?

Be curious. Be open. Be ready for anything.

What was the biggest challenge in writing your memoir, ‘Desperate to Be a Housewife’?

What was the biggest challenge in writing your memoir, ‘Desperate to Be a Housewife’?

The story takes place from the ‘60s to the ‘80s, a time of enormous changes for women. But even as we embraced new freedoms, we couldn’t jettison the values we’d inherited. I found it challenging to portray this conflict through my heroine, Mona Venture (I changed everyone’s name, including my own), whose globe-trotting career as a reporter and misadventures with men serve as a kind of armor to dissemble the fact that she’s actually desperate to be a housewife.

Why did you want to write this book?

It’s a story that takes place against a backdrop of historic events, and I wanted to record that, especially for younger women curious about the sexual, political and cultural revolutions of a previous generation. But it’s also a personal story. Why do writers write? Because they have to. It wasn’t really a matter of choice.

Was there problem concerning the impact on people who appear in the book, even legal problems?

There hasn’t been so far… I did change the names of the people portrayed. Also, I’m still in touch with most of them and, while writing, showed them the pages in which they appear. This was a useful exercise – first, they helped me to remember details, and second, I was able to deal with any objections.

Are you planning to write another book?

I’m just getting started on a new book, working title ‘Footprints Through Time.’ It’s a fairly ambitious project in which I’ll use evolutionary genetics to try to find the prehistoric woman who connects me with my Malian-born adopted daughter. A search for our common earth mother…

Is your case – single-parent adoption – exceptional? We hear about gay adoption, but not so much about single adoption.

I don’t know how common it is, but it’s been going on for a long time in France. I adopted my daughter under French law, and have to say that the adoption bureaucracy was fantastic – supportive and efficient. There were other single people at the first information session I attended, including a man, and we were all encouraged to pursue the matter. Later, in Mali, a single woman from southern France was adopting a child at the same time as me. The one thing the French would not allow was adoption by an unmarried couple.

What are the challenges of raising a girl of Malian origins in France?

My daughter was one year old when I adopted her, and I feared she might encounter racism growing up here. But thankfully this has rarely been the case. She’s a normal Parisian teen with plenty of friends and a lot of attitude. That’s the biggest challenge – she’s a teen.

Why write a blog about cooking?

I was giving cooking classes in my Paris kitchen and wanted to collect my recipes in a book. A prominent cookbook agent told me I’d need thousands of followers to get a publisher interested. I was about to drop the idea when my daughter suggested I start a blog. And now I’m enjoying the blog so much that I’ve put the cookbook project on the back burner! Although I hope to return to it one day.

What do you think of the current state of cuisine in France?

It’s on a slippery slope. People are in a hurry, and that has seriously affected the quality of what comes out of the kitchen. Everyone’s using commercial foods. In bistros, vinaigrette has morphed into a revolting white sauce out of a bottle. At home, people are relying more on frozen food and takeaway. The genius of French cuisine is its use of natural products. Thank goodness for street markets.

What trends in food have you seen develop in Paris?

Bistros with creative young chefs that propose small plates of food to be shared by a tableful of friends in a convivial atmosphere. One of my favorites is Au Passage.

What’s your favourite dish?

What’s your favourite dish?

I like so many different kinds of cuisine. When I was living in Moscow I used to fantasize about going out to a Parisian bistro for crudités and steak-frites.

What’s your least favourite dish?

Brains.

What’s the easiest good dish you can recommend?

Poulet roti épicé (spicy roast chicken). Choose a free-range chicken. Coat with a mixture of 1 T. olive oil, 1/2 t. ground cumin and 1/4 t. cinnamon. Roast for about an hour in a medium-hot oven. Add salt and freshly ground black pepper just before serving. As I like to say on my blog, happy cooking!

More in Interview, Meg Bortin