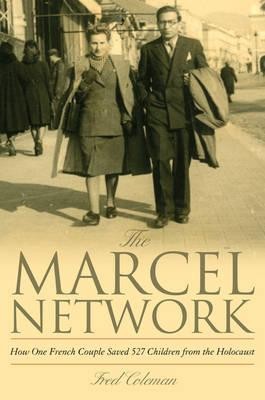

The Marcel Network: How One French Couple Saved 527 Children from the Holocaust

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

The streets of Paris honor its history and its heroes. Walking through the 12th arrondissement, you may pass the Place Moussa et Odette Abadi, a small, tree-lined square that pays homage to a young couple who founded and led of one of the most successful resistance efforts of the Holocaust. The Marcel Network is their story.

The streets of Paris honor its history and its heroes. Walking through the 12th arrondissement, you may pass the Place Moussa et Odette Abadi, a small, tree-lined square that pays homage to a young couple who founded and led of one of the most successful resistance efforts of the Holocaust. The Marcel Network is their story.

Fred Coleman, former bureau chief for Newsweek in Paris and in Moscow, relates an inspiring tale of courage in the face of unspeakable evil. It is a story of determination and persistence, of compassion and sacrifice. It is also the story of a love that flourished in the most horrific context and would last for nearly 60 years.

Moussa Abadi was 33 years old, an actor and graduate student in theater, and his future wife, Odette Rosenstock, was a doctor, just 28 years old. As the Vichy government implemented anti-Jewish laws and atrocities against Jewish citizens increased, it became impossible to ignore the mounting danger. Clearly, the time had come to act. With barely enough resources to sustain themselves, the Abadis began a clandestine operation that would ultimately save 527 Jewish children from deportation by placing them in Catholic institutions and with Protestant families.

This is the story of the Abadis, and it is the story of other French citizens who responded to a moral imperative, often at great personal risk. There are no minor players in this piece; each represented a link that was essential to the operation of the whole. As the cast of characters comes alive on the page, certain emerge as heroes.

This is the story of the Abadis, and it is the story of other French citizens who responded to a moral imperative, often at great personal risk. There are no minor players in this piece; each represented a link that was essential to the operation of the whole. As the cast of characters comes alive on the page, certain emerge as heroes.

Moussa found an invaluable ally in Paul Rémond, the bishop of Nice, whose aid was instrumental in the creation of the Marcel Network. Rémond gave Moussa an office on the ground floor of his residence, going so far as to help forge baptismal certificates and ration cards (which Moussa later destroyed, fearing the bishop’s handwriting would be recognized). At Rémond’s behest, Moussa took the pseudonym, “Monsieur Marcel,” and so the Marcel Network came to be.

Protestant pastors Pierre Gagnier and Edmond Evrard, would help to find Protestant families to shelter the children. Both the pastors and the bishop had historically helped the Jews. Rémond was speaking out against anti-Semitism as early as the 1930’s, and Pastor Evrard had been receiving Jewish children from Germany and Austria since 1930.

There were ordinary citizens, like a certain Madame Belliol, who asked to be given the “ugliest child, the most miserable, the one that nobody wants, and I will cuddle him.” Monsieur Brès, a civil servant who worked for the Vichy government, was so repelled by what he saw that he did what he could to privately oppose it. A few months later, he was executed by the Germans for helping the Resistance.

Parents had to be alerted to the danger and hiding places found for the children. False baptismal certificates and ration cards were forged bearing the children’s new names, and, of course, money was always a problem. But logistical considerations were only part of the story. There was the question of identity.

Hiding in Catholic institutions or with Protestant families, answering to their real names could place a child – and those who sheltered him – in jeopardy. Moussa began a process he called “depersonalization.” Each child was to lose his or her Jewish identity and learn a new Christian name. Moussa said later he found this the most difficult part of the process, to strip a child of his identity.

Hiding in Catholic institutions or with Protestant families, answering to their real names could place a child – and those who sheltered him – in jeopardy. Moussa began a process he called “depersonalization.” Each child was to lose his or her Jewish identity and learn a new Christian name. Moussa said later he found this the most difficult part of the process, to strip a child of his identity.

Much has been written about the behavior of Christians in Europe: the thuggish Milice, neighbor denouncing neighbor, even an ineffectual Pope who found it easier to go along to get along, hiding behind a shield of neutrality. With the exception of one interview, Moussa and Odette remained silent about the Marcel Network in the years after the War. Neither their friends nor even some of the children who were rescued were aware of the roles the couple played. It is a story that needed to be told, and Coleman is a skilled raconteur. He gives a balanced account, revealing just how much the Catholic Church, French Christians and Jews themselves did to save Jewish lives.

The book has been meticulously researched, and each chapter is annotated. The Marcel Network deserves a place on the reading list of any program in Holocaust studies. At the same time, it is a page turner, with sympathetic characters and action that builds.

Jane del Monte has studied and worked for a number of years in Paris. She directs ARTS in PARIS tours, with a focus on French culture and l’art de vivre. When she isn’t in Paris, she writes about it.

More in book, book review, Fred Coleman, Paris book reviews, Paris books, The Marcel Network