Flaubert’s Sentimental Education: Paris in the 1840s

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

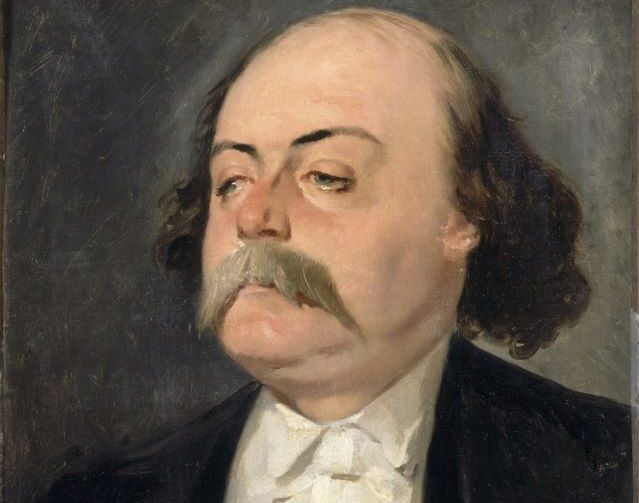

The title of Gustave Flaubert’s weighty final novel, L’Education Sentimentale, meaning “an education of the heart” tells us that the novel will center on the amorous adventures of the main character, Frédéric Moreau. But it is set mainly in Paris, and readers also get to know many areas of the city in the 1840s and meet a whole range of characters from that most turbulent decade. Opening in the reign of King Louis-Philippe, the story is set against the events which led to his abdication in 1848 and the beginning of the Second Empire. This is Paris in exciting times, actually witnessed by Flaubert in his 20s and retold in this novel, written 20 years after they happened.

Early in the story, we see the young Frédéric leave the provinces for Paris to study law, just as Flaubert himself had done. A desultory student, Frédéric attends lectures for only a few weeks, abandoning the Civil Code “before they reached Article 3” and turning instead to other interests; the Louvre, the theater, a new dancehall called the Alhambra on the Champs Élysées, where schoolboys smoke cheroots and prostitutes come “hoping to find a protector, a lover, a gold coin.” Unsurprisingly he fails his first exams and descends into a “bottomless pit of lethargy.”

A view of the Jardin des Champs-Élysées in the 1860s, by Charles Fichot. Public domain.

Frédéric’s amorous adventures are all set against a very Parisian backdrop. In the opening pages, on a boat trip out of Paris to his home town of Nogent-sur-Seine, he first sees the woman on whom his heart will be set for the rest of the novel. Madame Arnoux, wearing a wide straw hat with fluttering pink ribbons, is to him “like an apparition” and neither her elusive quality nor the presence of her husband and children stop him from experiencing a yearning for her and “a painful and infinite curiosity” to find out everything about her. Back in Paris, everywhere he goes makes him think of her. Seeing palm trees in the Jardin des Plantes, he dreams of taking her to “faraway places” and in front of old paintings in the Louvre, “his love reached out into vanished centuries to embrace her.”

Jardin des Plantes/ courtesy of MNHN, Jerome Munier

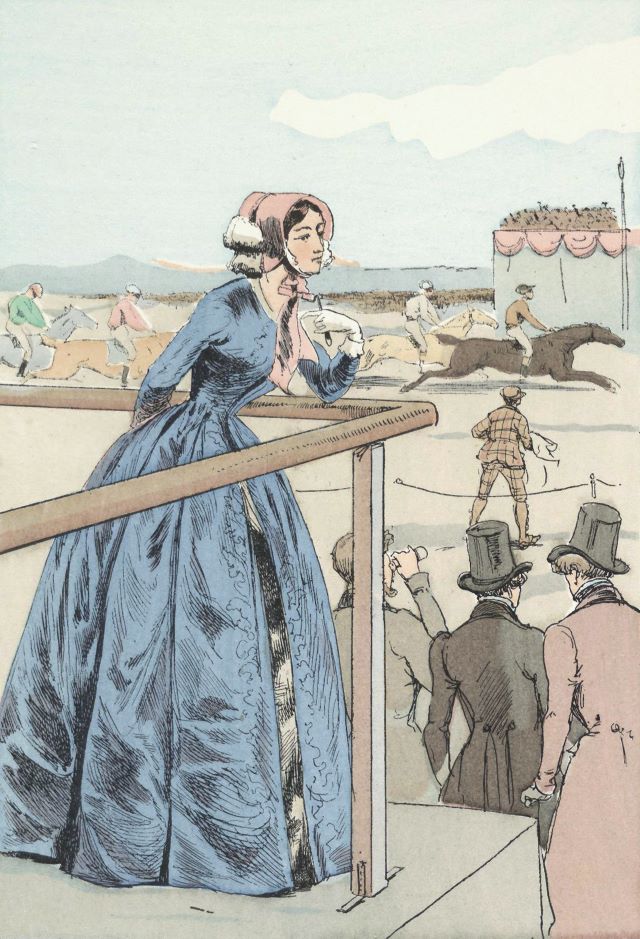

But Frédéric must find other women if he is going to have real romantic relationships and again this takes the reader out and about in Paris. With the courtesan Rosanette Frédéric saunters along the Rue du Bac, then lingers on the Pont Royal to admire the towers of Notre Dame against a blue sky. He hires a horse-drawn carriage to drive her along the Seine to the races on the Champ de Mars. There then follows a detailed description of the event, where smartly dressed spectators watch from rows of tiered seating as the horse racing gets more and more exciting: “The crowd shouted, the wooden stands shook with their stamping.” Flaubert himself was surely at the races on this very spot.

A stand at the Champ de Mars races © François Courboin/ Wikimedia commons

The backdrop to all of this is Paris heading towards revolution and many of the different factions are introduced through the huge range of characters Frédéric meets. The wealthy banker, Monsieur Dambreuse, whom Frédéric hopes will employ him, represents the aristocracy. To be entertained at his house is to see old Parisian wealth at its most extravagant: “The buffet resembled the high altar of a cathedral, there were so many dishes, covers, place settings, silver and silver-gilt spoons.” The talk is of “pauperism,” which many of the guests find “exaggerated.” Frédéric’s student friends have Republican tendencies; indeed his mother dislikes his friend Deslauriers precisely because he “refused to go to church on Sundays and held forth on Republican matters.” The more radical Republicans attack many accepted ideas: “The Académie Française, the École Normale, the Conservatoire, everything which could be thought of an institution.”

Ecole Normale © Public Domain

Flaubert was in Paris during the 1848 revolution, and his descriptions of what happened are partly from memory, supplemented by his extensive research from newspapers and eye-witness accounts. There are references in the early chapters to what is going to happen, such as a description of “men in smocks, delivering speeches,” carefully watched by patrolling policemen and, later on, Frédéric is invited by his friend Deslauriers to join a demonstration. Having “a more pleasant rendezvous,” he declines, but on his way to meet Rosanette he sees columns of students marching near the Madeleine, and hears “the strains of the Marseillaise” and shouts of “Long live the Reform.”

The retelling of the main events of the revolution is all intertwined with the events in Frédéric’s personal life which seem, to him, more important. He is awoken one morning while sleeping at Rosanette’s by the sound of gunfire from the Champs Elysées. Going down to the streets, he finds the aftermath of rioting and the “beginnings of a barricade.” Men are “haranguing the crowd with frenzied eloquence,” drums are beating, the National Guard is called, people are wounded and killed. Even more momentous events follow: the rush into the Palais Royal where “the rabble draped themselves ironically in lace and cashmere,” the abdication of Louis Philippe and the declaration of a republic. The violence and horror are shown in telling detail. At the Palais Royal “the water from the broken fountain mixed with blood and made puddles on the ground,” yet when the monarchy falls there is a jubilant “carnival atmosphere” on the streets.

Soon after this, as the politics which will lead to the establishment of Louis Napoléon and the Second Empire play out, we see that Frédéric is focusing again on himself and his affairs of the heart. While the future of Paris, and of the whole of France, is being tussled over, Frédéric is staying out at Fontainebleau with Rosanette, then getting involved in a whole series of romantic entanglements: wondering whether to propose to the daughter of a neighbor from his home town, ingratiating himself with Madame Dambreuse, now a rich widow, still always yearning for Madame Arnoux and gradually being drawn into her husband’s financial demise in order to protect her.

Fontainebleau and the lake. © Sharad Sovani/ Wikimedia commons

So yes, this is a novel which transports you to the Paris of the 1840s, to the everyday life of a huge range of characters, to so many corners of the city which we still visit today and to the political backdrop of a momentous decade. But perhaps most of all it is, as the title indicates, the story of Frédéric and his development, through his relationships with women, from impecunious student to disillusioned adult.

Lead photo credit : Gustave Flaubert par Pierre François Eugène Giraud © Public domain

More in book, French history, French revolution, Revolution, romance, writing in Paris