The Infamous Art Heist at the Musée Marmottan Monet

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

On a quiet Sunday morning in the leafy suburbs on the edge of the Bois de Boulogne, the first visitors to the Musée Marmottan Monet were followed inside by other fee-paying visitors who had not come to admire the paintings but to steal them by force.

It was October 27th, 1985, and with the museum open to the public, and consequently all the museum’s security systems switched off, the thieves swiftly donned masks and threatened both the 40 visitors and nine guards at gunpoint.

courtesy of Musée Marmottan Monet

The guards and visitors were forced to either lie face down on the floor or locked in the clothes closet under the control of two of the masked thieves. The three remaining robbers proceeded to remove nine paintings, smashing the glass off one of them to facilitate its removal.

It was a breathtakingly audacious robbery which from start to finish took barely five minutes from 10:15 to 10:20 a.m. In those few minutes, the thieves loaded the nine fragile art works into the trunk of a grey sedan which was blatantly double parked in front of the museum, and fled the scene.

This was no random smash and grab. The paintings stolen were the very best the museum possessed, including the priceless 1872 painting, “Impression, Sunrise” by Claude Monet. (Although “priceless,” it was estimated to be worth at least $4.75 million.) The other paintings by Monet included “Camille Monet and Her Cousin on the Beach at Trouville,” “Portrait of Jean Monet,” “Portrait of Poly,” “Fisherman of Belle-Isle” and “Field of Tulips in Holland.” Auguste Renoir’s “Portrait of Monet” and “Bathers”, and Fukuko Naruse’s “Portrait of Monet” along with “Young Girl at the Ball” by Berthe Morisot – all were unceremoniously loaded into the trunk of the sedan.

Monet – Impression, Sunrise (C) Claude Monet, Public Domain

It was obvious to all that these paintings had been stolen to order. The haul would have been even more devastating had six Impressionist paintings not been sent to New York for an exhibition several days earlier.

The question was who had them… and where? For almost two years it seemed that the paintings had disappeared into thin air, and at a conservative estimate of $12.5 million for the nine paintings, answers were imperative.

Musée Marmottan Monet. Credit: Visit Paris Region

Of course, Monet’s “Impression, Sunrise” was the undisputed star of the show. It was painted in 1872 and first shown at the Exhibition of the Impressionists in Paris in 1874. The painting was credited as the inspiration for the term “Impressionism.” The painting was one of a series of six Monet painted of the port in his hometown, Le Havre. The paintings depicted the port during different times of the day – dawn, day, dusk and dark. The viewpoint changed, some views from his hotel room and others from the water itself. However it was “Impression, Sunrise” that made the biggest impact in an exhibition called “Painters, Sculptors, Engravers etc inc” in the same year. Monet, Degas, Pissaro, Renoir and Sisley led the exhibition of some 200 works, seen by some 4,000 people. They were not all sympathetic to this new way of painting. Monet in particular was singled out for his loose brush strokes and hazy colors, all far from traditional landscapes and classic idealized beauty. Fortunately others saw the beauty, the depth of color, the reflective light on the water, the painting’s luminescence. Theodore Duret, French journalist and art critic, was one of the first advocates of Impressionism. He wrote that “Monet was the Impressionist painter par excellence.” Impressionism may have been in its infancy, but it was well and truly born, although it is doubtful that any of these artists could have imagined that more than 100 years later, their paintings would be worth such enormous sums of money and be the targets of armed robbers.

Yves Brayer (1930) (C) Agence de presse Meurisse, Public Domain

It was certainly a robbery that shocked the art world to its core. Yves Brayer, the then curator of the Marmottan, said that this was the first time in his memory that museum art works in France had been stolen at gunpoint “like a bank robbery.” The theft was considered a sacrilege and was compared to that of the Mona Lisa from the Louvre in 1911. The loss to the museum was inestimable.

Mona Lisa (C) Leonardo da Vinci, Public Domain

The Musee Marmottan, located as it was on the very edge of the Bois de Boulogne, was originally a hunting lodge for the Duke de Valmy and was then purchased by Jules Marmottan in 1882. Left to his son Paul Marmottan, he added to his father’s collection of paintings, bronzes and furniture with his own items of particular interest from the Napoleonic era. Paul Marmottan bequeathed the home and entire collection to the Academie des Beaux-Arts who opened up the house as in 1934 as the Marmottan Museum. The townhouse with its perfectly preserved Empire-style decor still manages to retain an intimate feel; it is easy to imagine people living here despite its impressive collection of paintings, sculptures and illuminations. The museum, although originally mainly of interest to lovers of the First Empire, broadened its appeal first in 1957 when Victorine Donop de Monchy donated an important collection of Impressionist paintings that had belonged to her father, Doctor Georges de Bellio, who had been the physician to Manet, Monet, Pisarro, Renoir and Sisley. It was however in 1966, that the Marmottan established itself as the most important museum for Claude Monet‘s works when his son, Michel Monet, left the museum the entire collection of his father’s work, thus endowing, with one fell stroke, the largest collection of Monet’s paintings in the world to one museum.

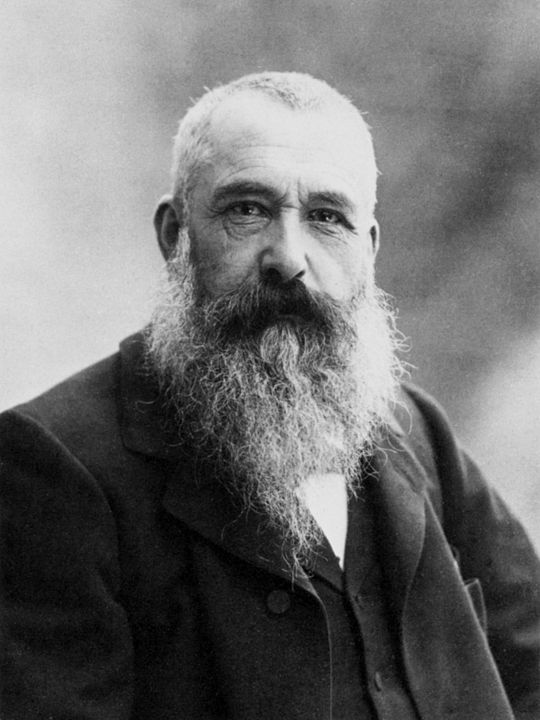

Portrait photograph of the French impressionist painter Claude Monet by Nadar (C) Nadar, Public Domain

(Michel Monet was born in 1878, the youngest of Claude and Camille Monet’s two sons. He was the subject of several of his father’s paintings. He married in 1927, but the couple remained childless. When Claude Monet died in 1926, Michel was the sole heir to the estate, but never actually spent any time in Giverny. He bequeathed the then run-down estate to the Academie des Beaux-Arts, who had the task of raising funds to restore the estate and its famous gardens to their former glory. Michel Monet died in a car crash in 1966 just before his 88th birthday. He is buried in Claude Monet’s vault in the Giverny cemetery.)

More important donations followed. In 1985, the adopted daughter of the painter Henri Duhem, Nelly Duhem, donated her father’s large collection of Post Impressionist and Impressionist works, including more Monet paintings, to the museum.

But the Musée Marmottan, without these nine precious paintings, could never be the same, and worse, it seemed that the police investigation had stalled. No one had any idea of either the identities of the thieves or where the paintings had been taken.

Two long years passed without news or hope. Then in 1987, Commissioner Mireille Balestrazzi, head of the special police art theft unit, traveled to Japan to recover four paintings by Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot. The paintings had been stolen in 1984 from a museum in eastern France. (Corot was a popular target for thieves. In 1998, a diminutive 13″x 19″ painting, “Le Chemin de Sèvres,” was simply sliced out of its frame in the Sully room, much to the embarrassment of the Louvre museum.)

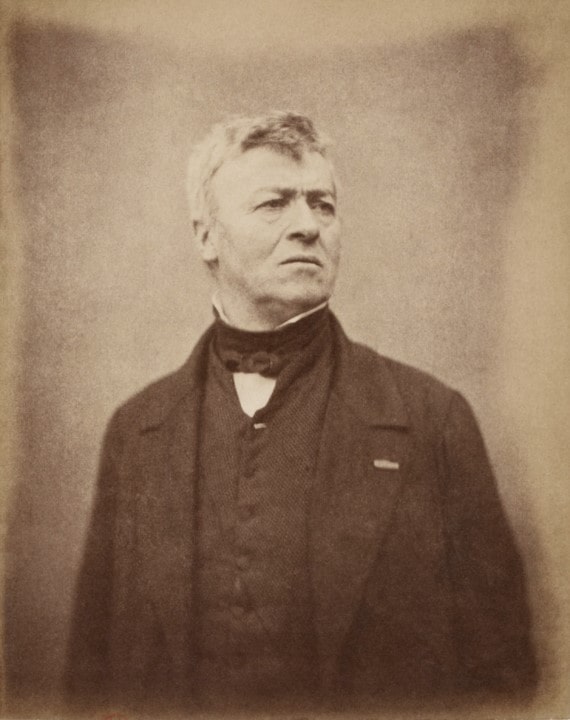

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (C) Victor Lainé, Public Domain

And here, the story becomes murky, the facts sparse. While Balestrazzi was in Japan, she received a tip that a Japanese collector had considered purchasing one of the nine Marmottan stolen paintings. The story was that representatives of the thieves had reached out to the Yakuza, Japan’s most bloodthirsty organized crime organization. Despite their denials in any involvement of the art thefts, a member of the Yakuza, Shuinichi Fujikuma, was not only in possession of one of the stolen Corots but was also one of the culprits in masterminding the Marmottan thefts. The main clue was not very subtle when a catalogue in Fujikuma’s apartment from the Marmottan museum showed all nine paintings circled in pen. Fujikuma’s accomplices, Youssef Khimoun and Philippe Jamin, were all serving prison sentences as part of an art theft syndicate when Fujikuma made their acquaintance during his five-year stint in prison in 1978 for the trafficking of heroin. The three of them had more than sufficient time on their hands together to plan their heist.

What becomes less clear is the why and when of the journey of the paintings, not discovered until 1990, and not in Japan but in an unoccupied villa in Porto-Vecchio, Corsica.

There were several other unanswered questions. Why did it take three years after the apprehension of Fujikuma to recover the paintings? Why was the Yakuza willing to tip off the French authorities? How did the paintings get from Paris to Japan and then to Corsica? Who were the masked gunmen? Were they ever apprehended? Balestrazzi did little to plug any holes in the mystery, merely reiterating that they had followed step-by-step testimonies that had led to the recovery of the paintings and that her task force had held off acting sooner due to the risk of the paintings being destroyed.

The paintings were still in remarkably good condition. They had suffered a little, easily repaired damage from humidity, but for the Musée Marmottan, it was but a tiny price to pay for the return of their valuable and much loved collection.

Arnaud d’Hauterives, the curator of the Musée Marmottan at the time, was quoted as saying that the return of the paintings “was the best Christmas present the museum could ever have had.”

Lead photo credit : courtesy of Musée Marmottan Monet

More in Art, Heist, history, Museum

REPLY

REPLY