Hemingway’s Wives

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 80 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

This month commemorates not only the death of Ernest Hemingway 60 years ago on July 2nd, 1961, but also his birth 122 years ago on July 21st, 1899.

It would be an understatement to say that Hemingway was both a complex and a contradictory man. He loved women, married four of them, had many affairs both inside and outside of marriage, and hated to live alone. He did not always treat his wives well, and like Picasso, his affairs overlapped, so that he always had the next woman waiting in the wings before he moved on.

Hemingway’s wives were just as contradictory and fascinating in their own right, and despite being deceived, bizarrely three of them became friends. Only Martha Gellhorn, fiercely independent, saw no need for the solace, forgiveness or understanding of her predecessor.

But it all started with Hadley Richardson, the wife that Hemingway always remembered lovingly with nostalgia and regret. The wife of whom he famously said in A Moveable Feast, “I wish I had died before I loved anyone but her.” But much as he tried later to renounce and blame his second wife Pauline Pfeiffer for his betrayal of Hadley, Hemingway was more than culpable of breaking Hadley’s heart and behaving with monstrous, disloyal selfishness.

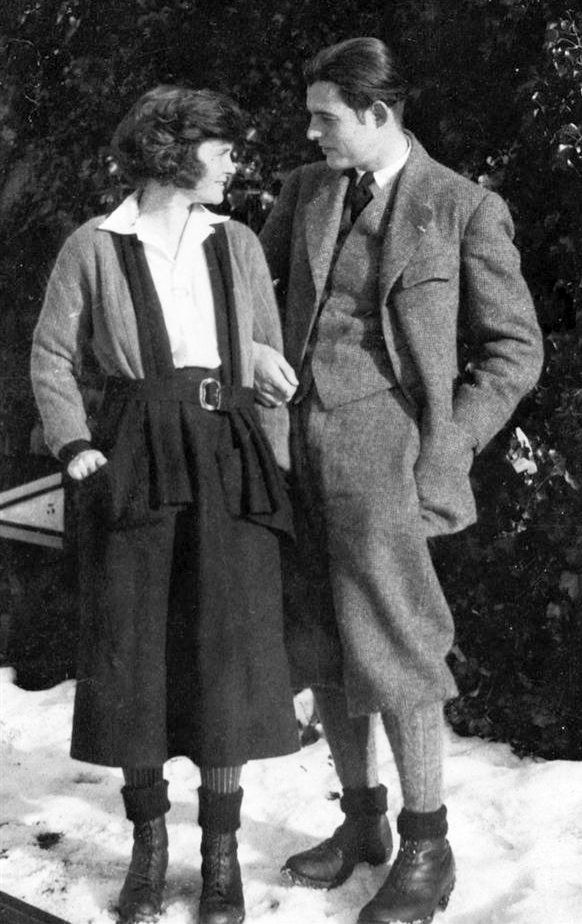

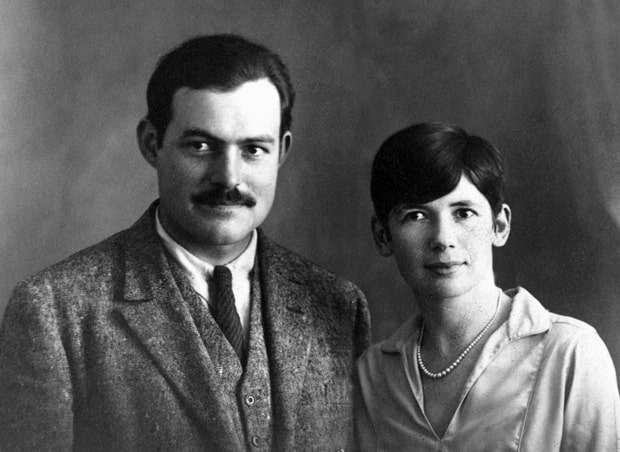

Ernest Hemingway with Hadley in 1922. © Public Domain

Elizabeth Hadley Richardson was eight years older than Hemingway. Unsophisticated, she was also still somewhat unworldly, due to the fact that she looked after her ailing mother throughout her 20s.

Born in 1891 in Missouri, she was a gifted pianist. Her father, like Hemingway’s father, had committed suicide in 1903 when Hadley was 12 years old; the parental traumas linked them together.

Hemingway and Hadley met inauspiciously at a party in Chicago in 1920, and immediately hit it off. Hadley reminded Hemingway of a nurse he’d fallen in love with in Italy, Agnes von Kurowsky. Despite Hemingway’s comparatively, young age – he was still only 21 – he was by far the more experienced of the two. Their courtship was short, often spent apart, but despite Hadley’s misgivings about their age difference, they married in September 1921, and rented a small apartment in Chicago. Hadley already benefitted from a small inheritance and then when an uncle died, leaving her another small inheritance, this combined with Hemingway’s employment as foreign correspondent for the Toronto Star, offered them enough financial independence to move to Paris.

The Hemingways’ life in Paris was well documented, from their first cheap apartment in rue Cardinal Lemoine to their second above a saw mill in rue Notre Dame des Champs. But Paris was really all about Hemingway, as he made a name for himself as a writer and met other writers like F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ezra Pound, James Joyce and Gertrude Stein, often in Sylvia Beech’s bookshop, Shakespeare and Co. Hadley was very much the “wife,” which was exactly how Hemingway wanted it. She was compliant, admiring, loving and stoic. She adored her husband, encouraged his writing, and made do sometimes with little food, insufficient heating in their cold apartment, and she wore unfashionable clothes without complaint.

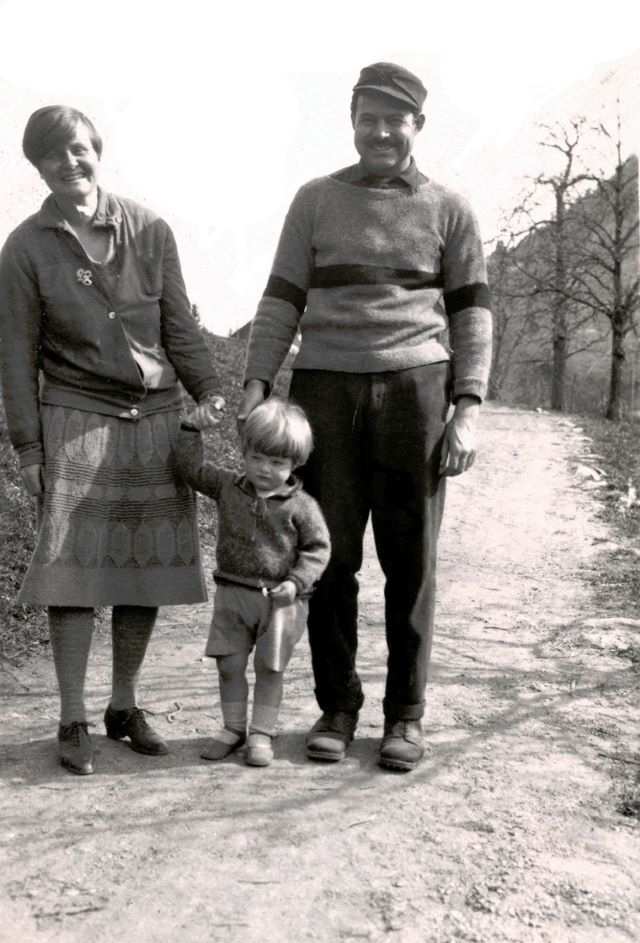

Their best times were skiing in Schruns in Austria. By then their son Bumby was born and Bumby would be looked after at the Taube while Hadley and Ernest skied. It was cheap to live there and Hemingway was editing The Sun Also Rises. But the word was already getting out about this new and promising writer, and Hemingway was falling for the flattery, falling for the easy charms of the rich.

Ernest Hadley with Hemingway and son John Hadley Nicanor “Jack” Hemingway (Bumby). © Author not specified. Public domain. Owned by John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston

Back in Paris, Hadley — bundled up in layers of clothing to combat the cold in their apartment — had already been introduced to sisters Ginny and Pauline “Fife” Pfeiffer at a party. The contrast between the three of them could not have been starker. Ginny wore mink, Fife sported chinchilla. Wealthy, fashionable, and great fun, Fife worked for Vogue magazine. The three became unlikely friends, although it was Fife who spent long evenings slumming it in the Hemingways’ apartment, calling in unexpectedly during the day, and inexorably becoming Hadley’s closest confidant. And it was this same Fife who wholeheartedly, relentlessly, and single-mindedly set her sights on becoming Ernest Hemingway’s second wife.

The affair was inevitable. Flattered by the attention of both women, and despite his low opinion of the rich, Hemingway could not help himself being swayed by the adoration of this stylish woman, the antithesis of his wife. The three of them soon became inseparable; wherever Hadley and Ernest were, so was Fife, still ostensibly in the guise of Hadley’s trusted friend.

Hadley knew in Paris that Hemingway was having an affair with Fife. It is almost impossible to guess her motives then, inviting Fife to Antibes where she was isolating in the Fitzgeralds’ villa with Bumby who had whooping cough. Hemingway was still in Madrid writing, now with the knowledge that when he left Spain, there were two women waiting for him in Antibes. If Hadley had hoped that the untenable situation between the three of them living in close proximity would force him to relinquish Fife, she had badly miscalculated, and the unhealthy threesome continued unabated under the hot southern sun. Hadley finally admitted defeat and granted Ernest a divorce. They had been married six years. In 1927, Hemingway married Fife and a new life began for all of them. In 1933, Hadley married another renowned journalist, Paul Scott Mower. They were together until his death in 1971. Hadley died eight years later in Florida in 1979.

Ernest and Pauline Hemingway in Paris in 1927 © Unknown author. Photograph in the Ernest Hemingway Photograph Collection, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library, and Museum, Boston. Public domain.

She remained friends with her ex-husband until his death.

Hemingway’s life with Fife in Paris could not have been more different from his first years with Hadley when he was still trying to make a name for himself and existing on little money. Not only was Fife wealthy, but her family was even wealthier. Her father was a major landowner in Arkansas, and her uncles were heads of an extremely lucrative pharmaceutical company. (Uncle Gus supported the couple financially, buying them a house in Key West and funding their African safari.) Not for the newlywed Hemingways an apartment with shared toilets on the landing, but a swish apartment in the rue Férou next to the Luxembourg Gardens. The success of The Sun Also Rises had catapulted Hemingway into another league, so with Fife’s money and his royalties, Hemingway’s life would never be the same. It is easy to forget in the blinding spotlight of Hemingway’s fame that Fife was a respected journalist in her own right. Clever and witty, she had graduated from the University of Missouri School of Journalism in 1918, then worked as a journalist in Cleveland and New York, before switching to Vanity Fair and Vogue magazines. However another writer in the family was not what Hemingway wanted. He wanted another wife like Hadley; he wanted to be looked after and taken care of.

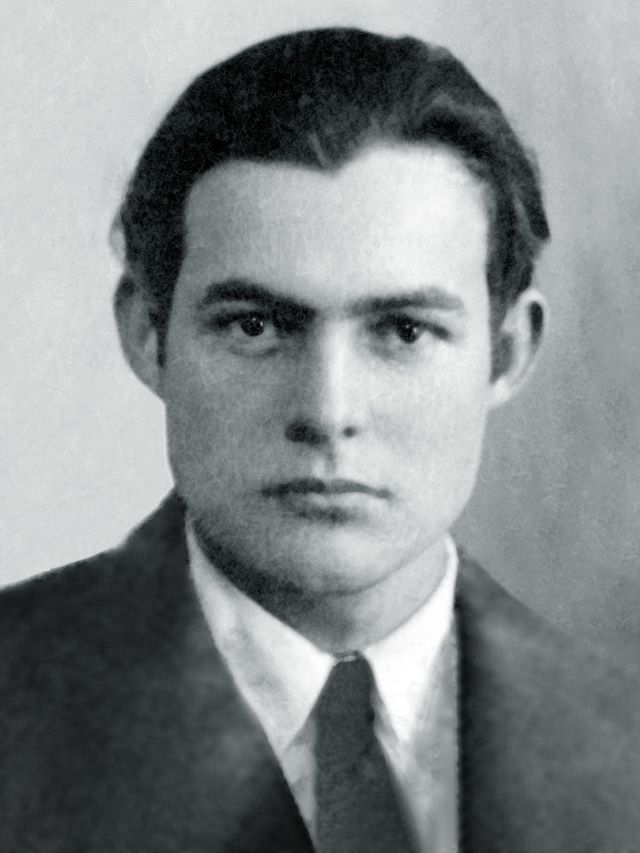

Ernest Hemingway’s passport photo in 1923. © Public Domain

Fife acquiesced without a murmur. She had got Hemingway, and later when they had two sons, whom she adored, Hemingway would still always come first.

By the end of 1927, Fife was pregnant and wanted to return to America. John Dos Passos recommended Key West and the couple left Paris in March 1928. In Key West, in the marvelous house Uncle Gus has bought them, Ernest was content at first. He went deep-sea fishing on his boat Pilar and frequented favorite drinking haunts. It was the perfect environment for writing, and Fife always had someone to take care of their two boys, Patrick and Gregory, when they wanted to travel.

Ernest Hemingway with sons Patrick and Gregory in Finca Vigia Cuba © Not specified author, owned by John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. Public Domain

But the civil war in Spain drew Ernest back to reporting from the front line, and Fife was left alone for long stretches of time. Worse, there have been rumors of another woman, another war reporter, a woman with whom her husband was openly sharing a hotel bedroom in Madrid. Her name was Martha Gellhorn. Fife had already met her two years earlier when Hemingway had brought her back to the house after meeting her in Sloppy Joe’s. Fife knew all the signs; she had already turned a blind eye to Hemingway’s six-month affair with Jane Mason, an affair that had just recently ended, and she had not been sure she could stand another betrayal. But Hemingway had returned to Spain three times against her wishes, and by 1938, Fife could no longer ignore the presence in his life of Martha Gellhorn. Ultimatums had not worked out too well for Hadley, and so it was with Fife. Hemingway chose Martha and Fife threatened never to divorce him. She had no intention of being as tractable as Hadley, of making things easy for the hated Martha Gellhorn. But in November 1940, Fife gave in by giving up. Ernest was never going to return to her. She granted him his divorce and 13 days later, he married Martha Gellhorn.

Fife spent the rest of her life between Key West and California. An incident on October 1, 1952 led to her untimely death. Their third son Gregory, sometimes known as Gloria later in life, was arrested for entering the women’s restroom in a movie theater which resulted in a telephone argument with Hemingway. Fife died of acute shock at the age of 56.

Gellhorn and Ernest Hemingway with General Yu Hanmou, Chongqing, China, 1941 © Public Domain

If Fife had miscalculated in her ultimatum to Hemingway, then he had drastically miscalculated the outcome of his marriage to Martha Gellhorn.

Their affair in the heady and dangerous atmosphere of the Spanish civil war, living under fire in Madrid, suited Gellhorn down to the ground. She was a war reporter, a journalist with no desire to cover anything but conflict, wherever and whenever it might occur. It was the most important thing in her life; the fact that Hemingway had not realized that says more about him than Gellhorn, who had never made any bones about where her priorities lay. And they weren’t being someone’s stay-at-home wife.

Gellhorn was born in 1908 in Missouri. She left Bryn Mawr College without graduating, already sure that journalism was the only path she wanted to pursue. Gellhorn already had had a stellar career before meeting Hemingway. She had been hired by Collier’s to report on the Spanish Civil War, and after their meeting in Key West, she had agreed to travel to Spain with Hemingway. Gellhorn was everywhere; in Germany reporting on the rise of Adolf Hitler, in Czechoslovakia just before the outbreak of WWII, and in Normandy during the D-Day landings, where she was famously the only woman to be a first-hand witness. This had been the catalyst of the break-up of the Hemingway marriage. Hemingway never forgave her for outdoing him; he had watched the landings from the safety of a boat offshore, and Gellhorn never forgave him for attempting to block her from traveling to Normandy, from offering his name over hers to her magazine Collier’s, and thus denying her press accreditation, and worse, knowing that she was then forced to take her life in her hands by crossing the Atlantic on a war transport ship that was loaded with explosives. Gellhorn’s fury was not tempered by finding Hemingway partying in the Dorchester Hotel in London, head bandaged, and surrounded by champagne bottles. Gellhorn, now sick to the back teeth of Hemingway’s bragging, let rip. She was in no mood to sympathize or play nurse to the patient she was rapidly tiring of. Unbeknownst to Martha, her replacement, Mary Welsh, was already waiting in the wings in another room of The Dorchester, and her husband had already asked her to marry him.

It was Gellhorn who had found the Finca Vigia in Cuba, which Hemingway eventually bought and where they lived after their marriage in 1940. Tired of war, Hemingway was content to settle down, but Gellhorn, nine years Hemingway’s junior, was still passionate about reporting on the battlefield, and Hemingway, left alone in Cuba, became increasingly irritated by Gellhorn’s long absences. Hemingway still expected his wife to be in his bed and not gallivanting around the world as a war correspondent.

Without doubt, Martha Gellhorn was the most extraordinary of all Hemingway’s wives. She had not wanted marriage; she had warned Hemingway that she wasn’t wife material, that she would’ve been quite content to remain his mistress, but Hemingway had worn her down, and of course she had loved him, and had allowed herself to be convinced that it could work. The marriage lasted four, often quarrelsome, embittered years. Hemingway’s betrayal in the Ritz Hotel Paris with Mary Welsh was the last straw. Gellhorn had been right. She was not marriage material – at least not for someone like Ernest Hemingway, who expected domesticity, a wife subservient to his needs, and willfully blind to his affairs. Martha Gellhorn, who became one of the most respected war correspondents in the world, did not fit the bill, as she had predicted from the beginning. This was a woman who was one of the first journalists to report from Dachau concentration camp in 1945, who covered the Vietnam war, the Arab – Israeli conflicts in the 1960s and 1970s, and at the age of 70 covered the civil wars in Central America and the invasion of Panama in 1989, before retiring from journalism. An operation to remove cataracts had left her with seriously impaired vision but she still managed one last assignment to Brazil in 1995 to report on the poverty in that country.

Three years later in 1998, aged almost 90, Gellhorn, increasingly frail, suffering from ovarian cancer and almost blind, took her own life in London. It was believed she had swallowed a cyanide capsule.

Wife number four, yet another journalist, was the buxom, blonde Mary Welsh.

Welsh was born in Minnesota in 1908, but moved to Chicago to work for the Chicago Daily News. She had married Lawrence Cook in 1938, but it was short lived and while on vacation in London, Welsh was offered a job at the London Daily Express newspaper, where she was often assigned to cover events in Paris. Welsh remarried Australian journalist Noel Monks during the war, but when she met Hemingway, the fact that neither of them were free agents, did not impede either of them from embarking on an affair.

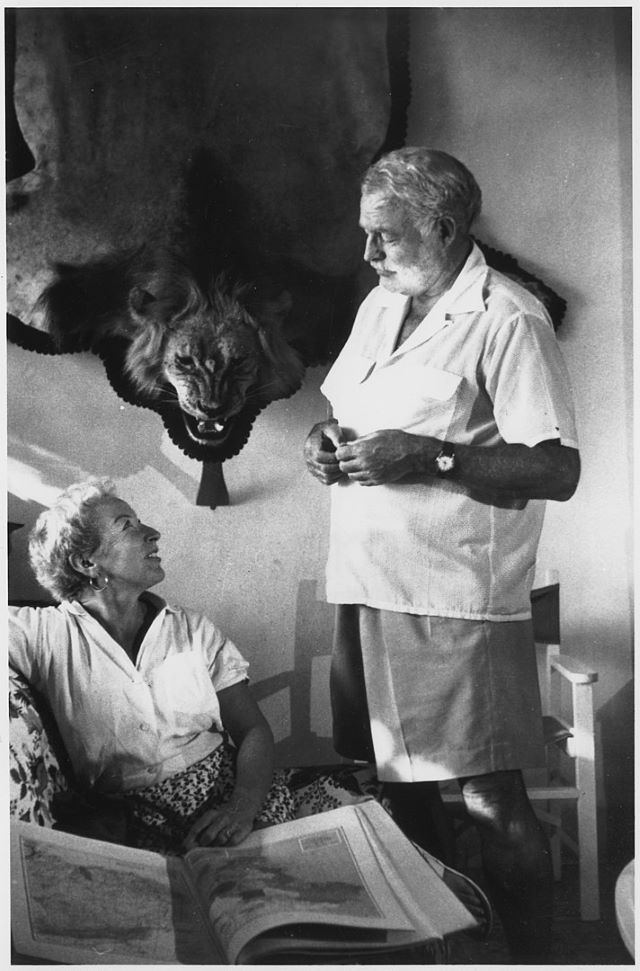

Ernest and Mary Hemingway on safari 1953 © Public Domain

They lived for a time at the Ritz Paris, Hemingway determined to deplete the hotel’s wine cellars before he left. The war was over, France had been liberated, and Hemingway was ready for a new wife. Mary Welsh knew the score. She had seen Hemingway drunk, morose, even violent, but like so many other women before her, Mary was entranced by this big bear of a man, was more than willing to give up her independence, to be the kind of wife that Ernest needed.

They married in 1946, just as soon as their respective divorces were finalized, and moved into the Finca Vigia in Cuba.

Hemingway had always been an intemperate drinker and he had suffered so many accidents and machinery accidents that it would be impossible to discount that his various head injuries had not affected his personality. His moods fluctuated from vile and bullying to sweet and loving. Mary put up with all of it. On the other side of the coin though, Mary had a previously unimagined life: New York, Italy, East Africa, France, the fiesta at San Fermin, days out fishing on the Pilar, living in the Finca Vigia with its servants and cooks, surrounded by Hemingway’s cats and scented hibiscus. Like his wives before him, Mary put up with his affairs, his juvenile obsessions with young women, his black dog moods. And then unexpectedly, her husband’s career was revitalized with the publication of The Old Man and the Sea and his Pulitzer Prize. It appeared that Ernest Hemingway was back on top of the world.

Of course it’s a long way down from that summit. Hemingway refused to stop drinking, his medecine cupboard was stuffed with drugs for high blood pressure, high cholesterol and pain killers. His weight fluctuated wildly, his eye sight was often blurred, he suffered headaches, but his mood swings were becoming more unpredictable, unpleasant, sometimes violent, and it was Mary Welsh Hemingway who most often bore the brunt of them. The political situation in Cuba, and Hemingway’s increasing paranoia that the house was bugged and the I.R.S were after him, resulted in the couple leaving Cuba in 1959 and moving to Ketchum. Hemingway’s mental state declined, he felt that he could no longer write and twice Mary had him committed to the Mayo Clinic for electric shock treatment under the guise of treatment for high cholesterol. Hemingway was discharged from the clinic and in the early hours of July 2nd, 1961, he shot himself with his double barreled shotgun in their home.

Ernest and Mary Hemingway at the Finca Vigia Cuba © wiki commons

Determined to protect her husband’s reputation, Mary told the press that his death had been accidental, that he was cleaning his gun to go duck hunting later that morning. (She later told them the truth about his suicide.)

Mary died in New York City in St Lukes Hospital at the age of 78 on November 26th, 1986. She stipulated that she be buried next to her husband in Ketchum.

Mary Welsh Hemingway was the last and longest lasting of Ernest Hemingway’s wives. The only marriage that had not ended in divorce.

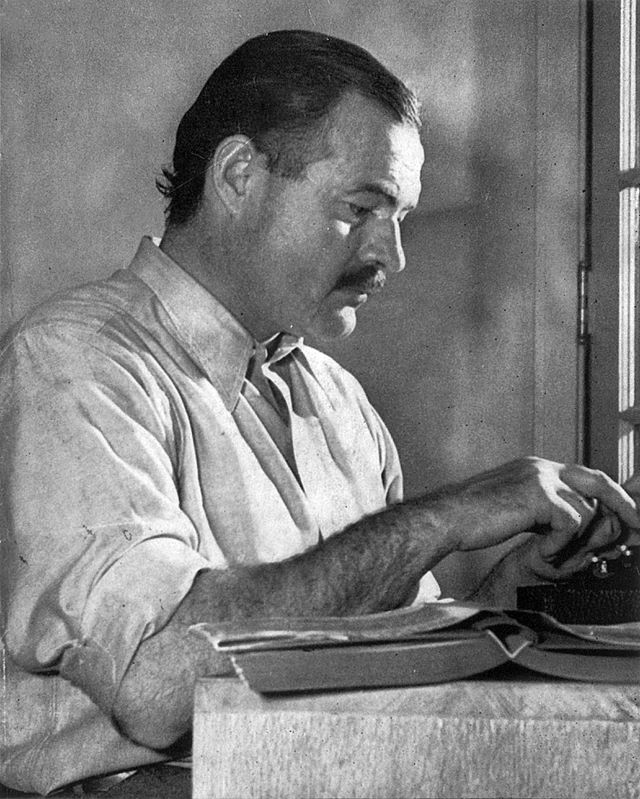

Lead photo credit : Ernest Hemingway © Lloyd Arnold, Public Domain

More in anniversary, Ernest Hemingway, Hemingway, Hemingway's wives, women in art, women in history, women in love