Remembering Paris: Monsieur Poisson & the 24 Hours of Le Mans 1969

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

It was all Sarah’s idea. I wondered if the effects of our late night at Le Tabou hadn’t quite worn off… Getting home at 5 a.m. on Sunday morning, my day off, usually meant a very lazy, long lie-in.

“I think we should go to the 24 hours Le Mans.” She’d said.

I remember my reply as being unprintable.

It’s possible that Sarah’s hangover was not as bad as mine. It could just have been of course that I was far lazier and unwillingly to contemplate the logistics of getting to Le Mans and back from Paris on a Sunday. And wouldn’t Le Mans be full of spectators already? And would any trains be running? And what time would we get back? And what…and what and what…?

I was wasting my breath and should have known better.

I met Sarah in the summer of 1968. I was camping in San Sebastian and Sarah and her friend offered me a lift back to Paris. She decided there and then that she too, would be an au pair in Paris and escape her tedious secretarial job back in Haywards Heath. By January 1969 she was having her first interview in Paris as an au pair.

I remember it with excruciating clarity. Determined that she would not suffer the experience of my first two au pair positions (lasting one week and two weeks respectively, they were so grim), I accompanied her to the interview. I have never been forceful, nor confrontational but on someone else’s behalf, a whole new (and somewhat unwelcome) side of me appeared.

How she got the job after that I’ll never know, but Janine, her employer, had been so amused by my performance that she nicknamed me Mother Goose.

I should also add that I had been almost suffocating with envy during the interview. Not only did Sarah’s prospective family live in a beautiful apartment in a stunning building entered through an immense courtyard, BUT it was in rue des Saints-Pères in Saint-Germain-des-Prés– a hop, skip and a jump from Le Tabou. AND she had her own room at the top of the building. Albeit a maid’s room with the dreaded squat toilet, but sometimes independence means holding your nose and searching for your wellies…

With even more galling good fortune, the family were lovely too.

Axel, Janine’s American husband, worked for the New York Herald. We’d called in to say hello and I’d moaned to him about Sarah’s latest idea. I suppose I was hoping for back-up. Instead, he thought it was a brilliant plan and scribbled a note for a journalist colleague who was covering the race at Le Mans. My heart had sunk; there was no way out now, plus we had to wave a note at anyone we saw to find a man who wouldn’t know us from a croissant. But it wasn’t until I read the name on the envelope that I gave up all hope.

Monsieur Poisson.

“Monsieur Poisson?” I said weakly. “Is this a joke?”

Axel said it wasn’t a joke and Monsieur Poisson couldn’t help his name.

Who on earth was going to take us seriously? I gave the note to Sarah. “I’m not doing it. I draw the line in asking for Mr Fish. You can do it.”

It was all astonishingly easy. We hitched to Le Mans: one lift the entire way and when we arrived outside the track, two young Frenchmen who had spent the night there, gave us their tickets. Monsieur Poisson’s note was waved at all and sundry-barriers were lifted, turnstiles opened, until suddenly there we were, down in the actual Pits at Le Mans. We could not believe it. The noise and the smell were simply indescribable. The excitement overwhelming. We never found Monsieur Poisson. Perhaps he wasn’t there at all– we didn’t care– his name had been enough to shuffle us through the 400,000 spectators to the track side and we’d never forget it.

We didn’t know at the time that Le Mans 1969 was to turn out to be an historical race, a turning point for this 24-hour event.

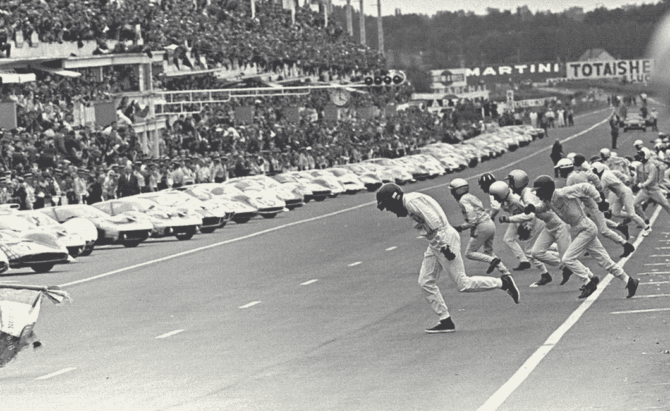

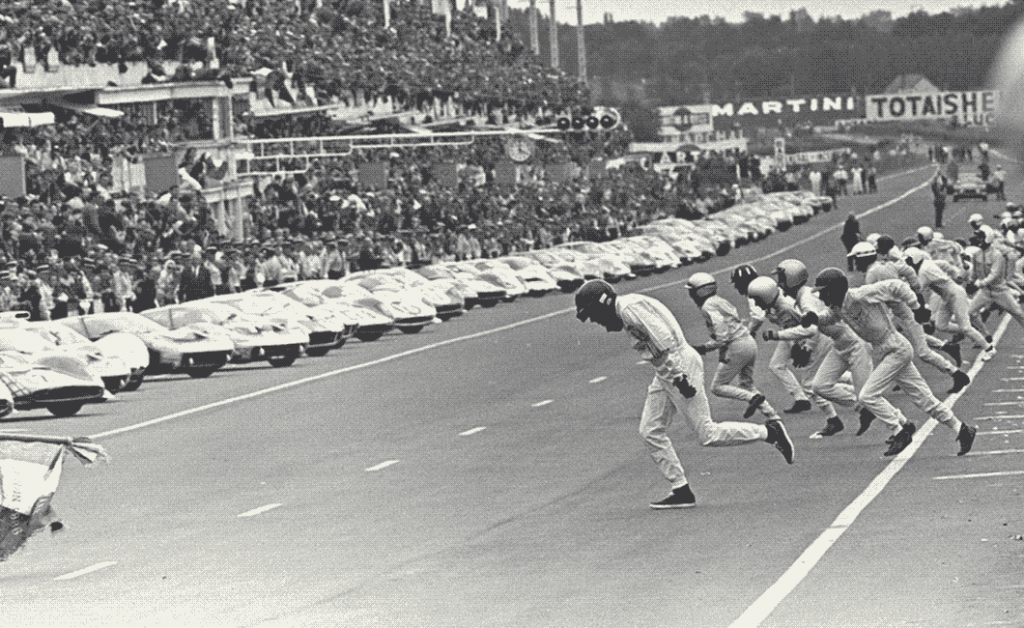

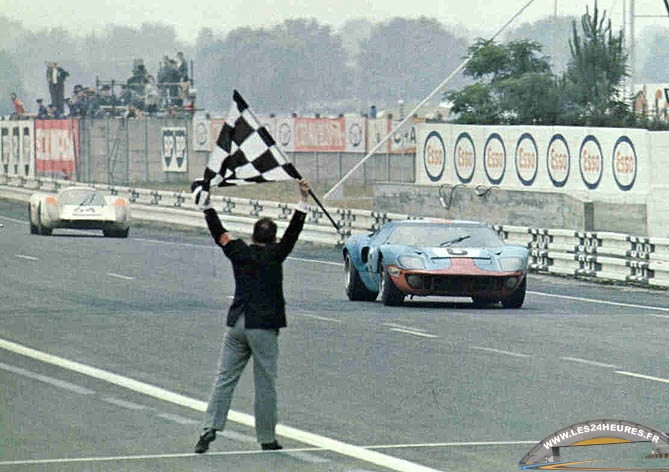

June 14th, 1969 was to be the very last time of the traditional Le Mans start where drivers ran across the track to their cars. Jackie Ickx, the 24 year old Belgian driver and eventual winner, demonstrated against the immensely dangerous practice by walking slowly to his car and meticulously fastening his seat belt. He consequently started last at the back of the field.

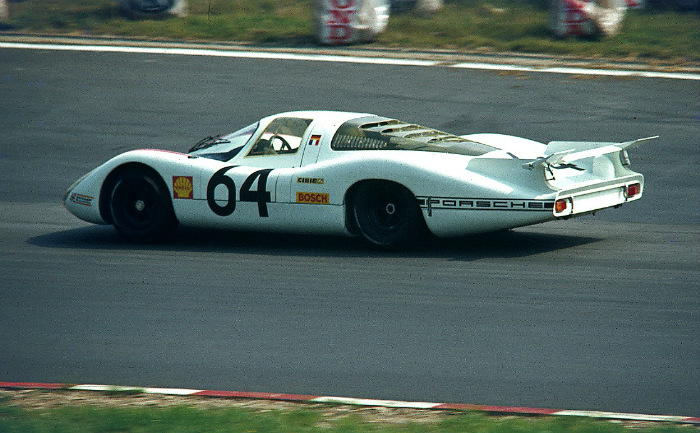

Tragically, John Woolfe, a ‘gentleman driver’ who had entered his powerful Porsche 917 privately, lost control of his car just before the end of the first lap and careered into the barrier. Drivers reported that part of his door had flown off and damaged the wing, speculating that in his rush to start he had not closed his door properly. On impact, Woolfe– who had not fastened his seat belt– was thrown from the car and killed instantly.

In 1970, the traditional start was discontinued; drivers had to be already strapped into their cars before the race started. Additional safety measures were put in place and safety barriers were erected around the circuit, especially at Mulsanne Straight which originally had been an open stretch of road with no protection from trees, embankments or even houses.

The dramatic finish of the 1969 Le Mans had Hans Herrman and the safety conscious Ickx passing each other on the last lap with Ickx winning by a matter of seconds.

Exhausted but exhilarated, with the sound of roaring engines still ringing in our ears, and the smell of petrol fumes embedded in our skin, we made our way back to Paris.

“Oh”, said Sarah, “Just in time for Le Tabou.”

Who was I to argue?

Lead photo credit : The 24 Hours of Le Mans, courtesy of "Les 24 Heures"

More in 24 Hours of Le Mans, Jacky Ickx, Paris in 1969