Lauren Groff Headlines a Stellar Faculty at the Paris Writers Workshop

Lauren Groff and other Paris Writers Workshop author-instructors on inspiration in France.

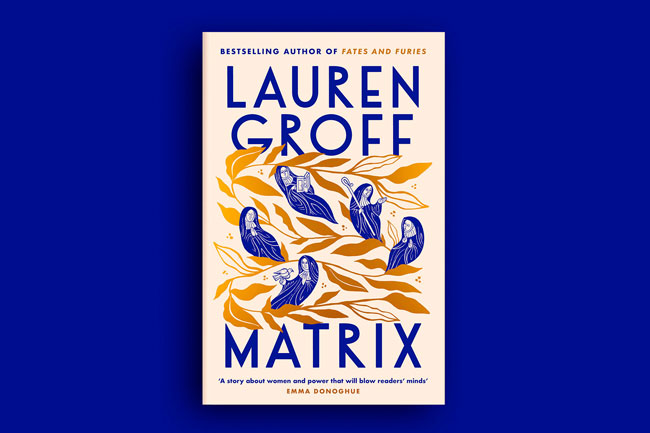

Lauren Groff is a novelist and short-story writer who’s been on the ascendancy since the Obama Administration, when the U.S. president himself plugged her breakout novel Fates and Furies. That novel was nominated for the National Book Award, as was her most recent book, The Matrix. It’s fitting that Groff is coming to teach this summer at the Paris Writers Workshop — not only The Matrix (about the medieval religious Marie de France) but her other writings have a link with France.

Her work has always been imbued with a strong sense of place. Her first novel, The Monster of Templeton, was based on her hometown of Cooperstown, NY. But while she loves the sense of narrative intimacy that comes with fully inhabiting a setting, she also feels a sense of otherness, or difference — of being a stranger in a strange land. She gave her fictionalized town the slightly gothic name Templeton, and there was that monster. (She also has an inveterate bookish sensibility: “Templeton” derives from a work by James Fenimore Cooper, whose family founded the real town.)

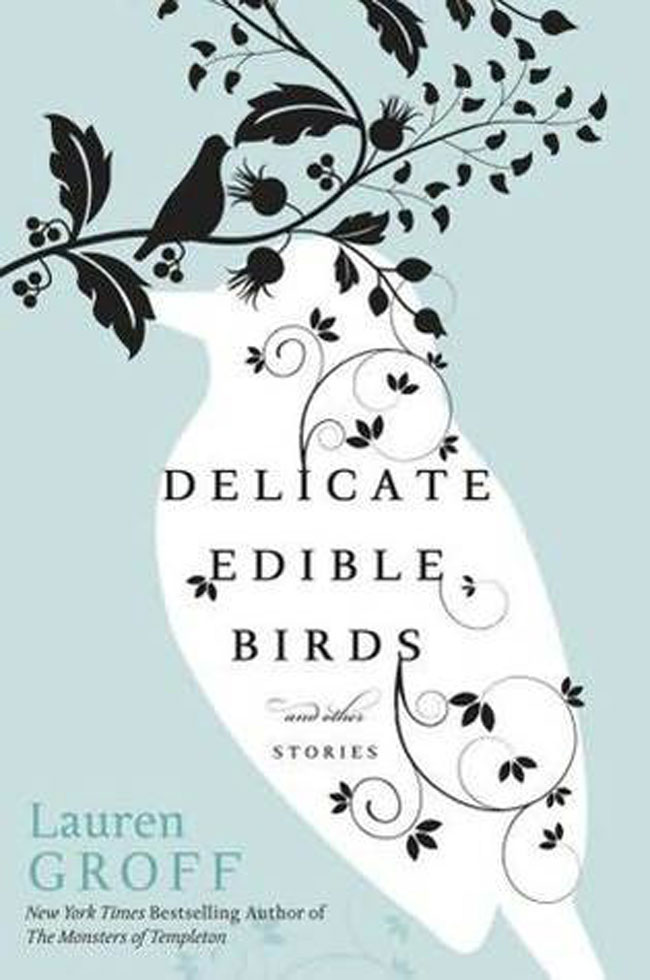

Groff’s attachment to France dates back to an early age. As a teenager she was an au pair in France, and for her junior year abroad, she spent time in Nantes. As her writing attests, she appreciates not only the picturesque, traditional qualities of the provincial terroir, but also its oddities. The eponymous story in her first collection, Delicate Edible Birds, featured ortolans, a delicacy people down whole — beak, feet and all. (It was a favorite of François Mitterrand.) I first met her when she gave a “breakfast talk” at the Vincennes Americas Festival, speaking in proficient French and more than holding her own with a very literate public, expressing both affection for and knowledge of French culture.

Her most recent story collection, Florida, was also nominated for an NBA. It intensely depicts the still overweening nature in that state as well as the ways we humans are defiling it. It’s an obvious but effective metaphor for our current cataclysmic tête-à-tête with climate and the environment. But Florida also includes two remarkable stories set in France, once again in la France profonde. “For the Love of God, For the Love of God” recounts how an upscale vacation idyll strains the financial-class differences between two American friends. The near novella-length “Yport” is a picaresque but claustrophobic work about a woman and her two young sons. The strange settings destabilize her — to the degree that she comes to hate the subject — Guy de Maupassant — of a literary study she’s working on.

I asked about her approach to teaching the craft of the novel. She recognized that it’s a daunting task, especially within the one-week duration of the Paris Writers Workshop (PWW).

“The novel is a magnificently complex machine,” she admitted.

Her own novels often have an innovative structural form: proliferating genealogical family trees in the Monster of Templeton, alternating accounts of a marriage from husband and wife in Fates and Furies, dense historical detail in The Matrix.

“We will be breaking up the art form into separate parts,” she said, “each day concentrating on a new element.”

She also said she’d rely on a “didactic model” that would take a comprehensive approach to novel form.

“The class seeks to ask questions of the writer in order to try to reconcile the writer and their work as a whole.”

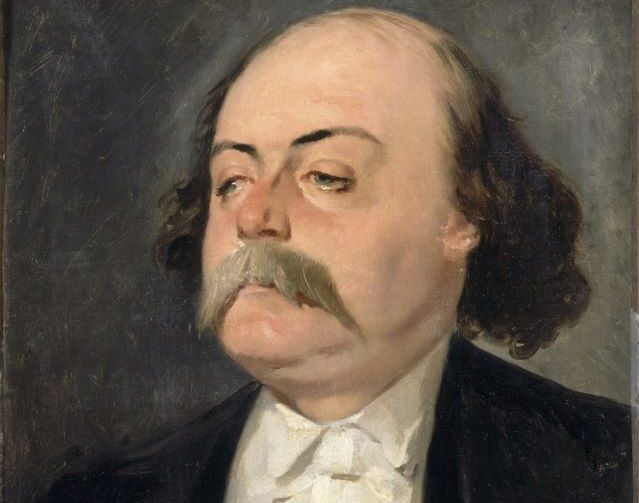

Gustave Flaubert par Pierre François Eugène Giraud © Public domain

Concerning how Paris, as opposed to the provinces, has given her inspiration, she took a somewhat Rabelaisian perspective (without naming Rabelais):

“I think often of the writers of the Belle Epoque who often assembled at rowdy dinners, and think about what it would be like to sit in a room with Flaubert, Turgenev, Zola, and Guy de Maupassant all present, laughing and joking, and singing, and having a glorious good debauch.”

She also sees a more serious and complicated side to her literary idols, not always so neat, just as her alter ego in “Yport” did with de Maupassant.

“I dream about what it might have been to overhear their conversations, and to watch them slowly lose their filters under the quantities of wine until they’re blurting out what they really think and feel, to see the true, flawed, messy humans behind the work that I love so deeply.”

Aside from teaching the novel seminar at the PWW, Groff will be reading with other faculty and students at the Red Wheelbarrow bookstore.

Jeffrey Greene, courtesy of Paris Writers Workshop

Jeffrey Greene, creative nonfiction

Jeffrey Greene will be teaching creating nonfiction at the PWW. A long-time faculty-member at the American University in Paris, he’s the author of a memoir, four “personalized” nature books, a book of mixed genre writing, and five collections of poetry. His work has been supported by the National Endowment for the Arts, the Connecticut Commission on the Arts, and the Rinehart Fund, and he was a winner of the Samuel French Morse Prize, the Randall Jarrell Award, and the “Discovery”/ The Nation Award. His writing has appeared in The New Yorker, Poetry, The Nation, Ploughshares, The Kenyon Review Online, and Agni.

When asked about a specifically Parisian inspiration for his writing he mentioned a person and institution that also marked my own beginnings in Paris: Odile Hellier and her landmark bookshop the Village Voice. In his own words:

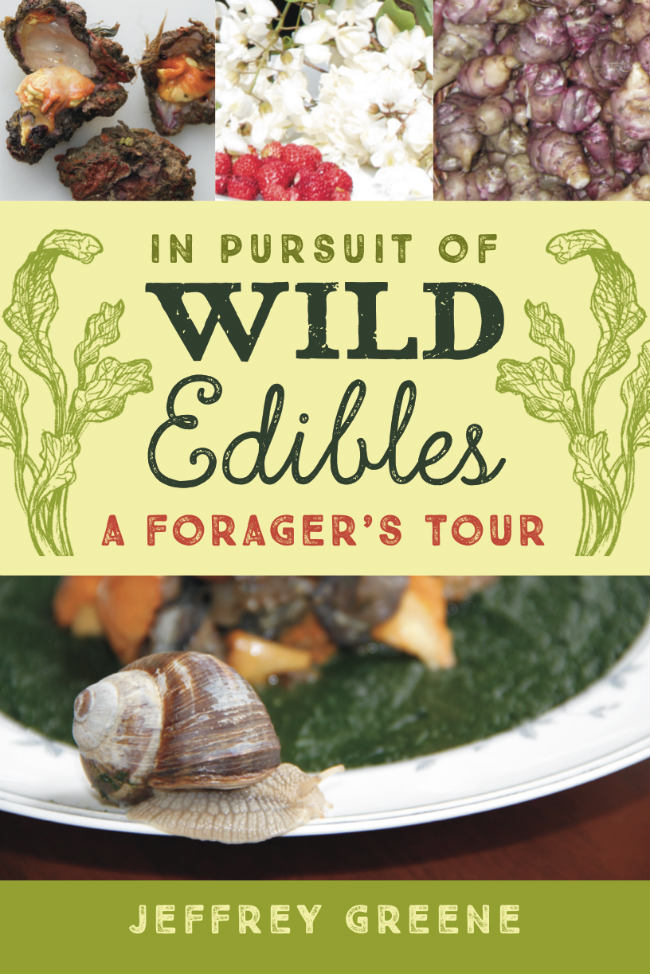

In Pursuit of Wild Edibles, A Forager’s Tour by Jeffrey Greene

JG: “Thirty-six years ago, I fell in love with a bookshop on the rue Princesse. It was only six blocks from my apartment. The Anglo-American bookstore took the name Village Voice, like the New York City newspaper. I knew no one in Paris except for a friendly band who invited me to play tennis in the Bois de Vincennes. When drained from a day of writing, I wandered over to the Village Voice and haunted a little alcove stocked with the most up-to-date English language poetry collections. Then I would browse the tables for new prose arrivals. I became familiar, at a distance, with the owner Odile Hellier from her introductions and incisive conversations with celebrated authors that she invited for events, always packed. More than a decade would pass before I’d get to share a few words with Odile, who’d finished graduate work in the Soviet Union and spent 10 years in the United States, before returning to France. I saw her come to life with the authors — dark haired, thin, attractive, focused, from a family with a painful history during World War II.

Temple at Lake Daumesnil at Bois de Vincennes. Photo credit: Guilhem Vellut /Wikimedia Commons

The Village Voice and Odile opened Paris literary life for me. To be honest, I don’t know how it happened. Partly it was publishing books and writers calling me. But I became friends with a group close to Odile. Charlie Williams and others called me to meet at the Village Voice and then have lunch. I introduced W.S. Merwin, Carolyn Kizer, and C.K. Williams at the store and soon got to know Adam Zagajewksi, Mavis Gallant, and Diane Johnson.

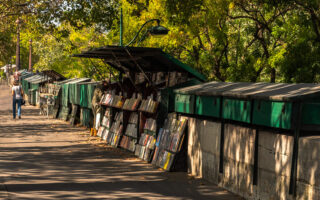

We have lost many of these writers, and we have lost a number of bookstores in Paris. The Village Voice is now a computer store that has sanitized the space of its lively literary ghosts. On the bright side, many writers couldn’t be more delighted with Penelope Fletcher, who owned and ran The Red Wheelbarrow, a wonderful bookstore in the Marais. It closed the same year as The Village Voice, in 2012, but has been resurrected by the Canadian, against all adversity, across the way from the Luxembourg Gardens.”

Jardin du Luxembourg. Photo credit: Rdevany/ Wikimedia commons

Jennifer K. Dick, poetry instructor

Jennifer K. Dick writes (and translates) not only poetry but critical texts in both English and French, as her most recent book That Which I Touch Has No Name shows. Her identity is as fluid as the three countries bordering the sleepy town of Mulhouse she resides in, or the Petite Ceinture that surrounds Paris and its suburbs where she also lives. She curates readings for authors in English and French that cater to audiences who are also between languages in their reading and writing interests. Stéphane Mallarmé’s visual writing opened doors not only to poetic exploration in her work but also to visual artists and writing about visual art. This led to collaborations with the Kunsthalle-Mulhouse Centre d’Art Contemporaine, where she co-curates a residency for French poets.

Jennifer K. Dick, courtesy of Paris Writers Workshop

JD: “Coming to France is, for some, a life goal. For me, it was a haphazard encounter that has turned into my second home. Growing up in Iowa, I never once thought I would go far beyond its farm-field borders. My poor ability to learn foreign languages seemed to confirm this. When I chose to do a Junior Year Abroad, I selected a university in England with no language requirement. But it was there that an accident turned my life in a new direction. That accident was attending a lecture open to anyone on campus by French literature professor Clive Scott. As he began speaking of the poetry of Stéphane Mallarmé, I felt — as Emily Dickinson said — the top of my head blow off. It floated away.

Portrait of Stéphane Mallarmé by Edouard Manet, 1876. Photo by Fern Nesson at Musée d’Orsay

Within a week I was reading all the translations I could find in the library and planning a trip to Paris. I knew that, as a young poet seeking new directions of linguistic exploration, I absolutely had to be able to read Un Coup de Dés in the original. When I arrived in France, though, I was lost. It took years to learn French at even a basic level and many flights and waverings about where I fit in in the world before I planted myself in France. France is a place that I have no illusions about being entirely within, entirely part of. I am and always will be an outsider. But this “other” status and existence (being the eternal l’étrangère) allows me all the room I need to be my outside.”

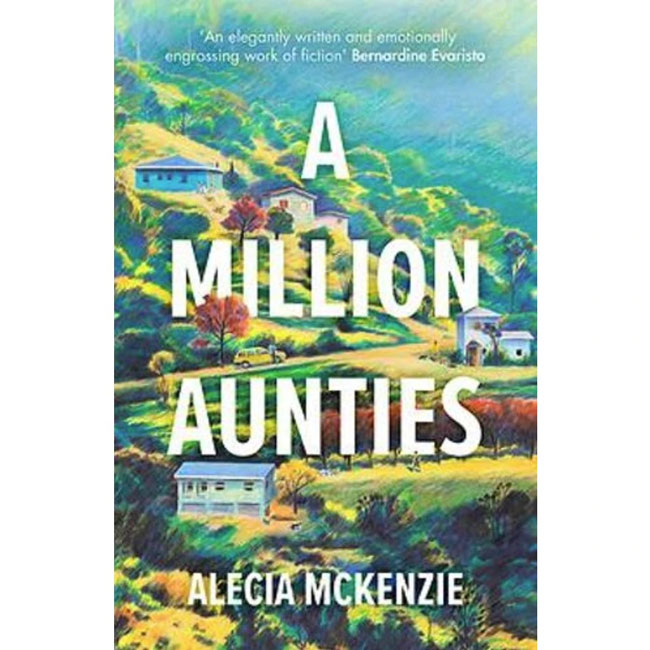

Alecia McKenzie, short story instructor

Alicia McKnenzie may be the most international member of the PWW faculty. She hails from Jamaica, studied at Columbia University, lived in Singapore and Belgium, and now lives in Paris. She is an accomplished fiction writer, journalist, author, and artist. Her story collection Satellite City and first novel Sweetheart won Commonwealth prizes, and the French translation of that novel won France’s Prix Carbet des Lycéens. Her latest novel, A Million Aunties, was published by Akashic Books and has garnered rave reviews from the New York Times and Publishers Weekly.

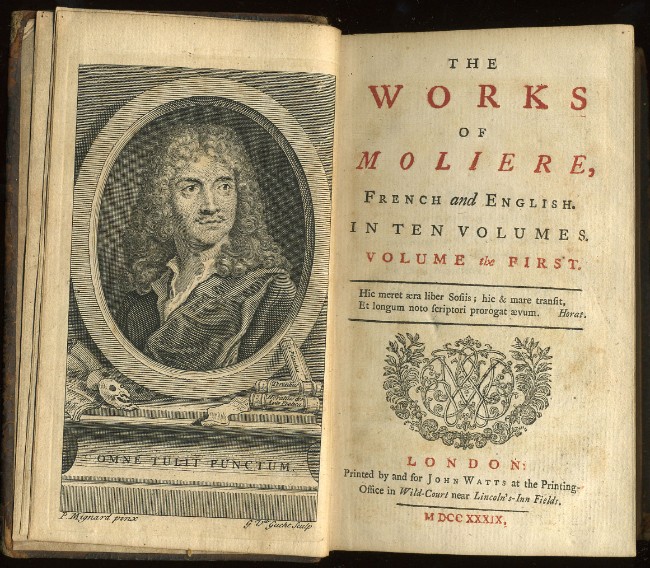

AM: “As I was in the arts stream in high school, I studied languages and literature. For French, we read Molière, Racine, Mauriac and other writers. One work that has stayed with me, though, is Molière’s Le Misanthrope – a play that was first performed in 1666 at the Palais-Royal in Paris. My classmates and I appreciated it for its humor and sharp observation of human nature, which still rings true more than three centuries later. One quote that I remember (or misremember) from the main character Alceste is that everyone wants to see their name in print. This was poking fun at the writer, and it seemed a message not to take oneself too seriously.

My class also had to read Le Malade Imaginaire and Tartuffe. After graduation, I had no intention of ever revisiting Molière; as there was so much else to read. But in 2018 in Paris, a friend invited me to see L’Avare at the Odeon Theatre, and although this was a modern staging, it took me back to my high-school days … and to being impressed by a long-dead French writer and his witty exposure of hypocrisy and human weakness. Great art is universal and timeless, non?“

First volume of a 1739 translation into English of all of Molière’s plays, printed by John Watts. Public domain

Full disclosure: Dimitri Keramitas is a volunteer co-director at the Paris Writers Workshop.

For details about the Paris Writers Workshop, visit the WICE website here.

Lead photo credit : Portrait of Lauren Groff, courtesy of laurengroff.com © Eli Sinkus

More in Authors in Paris, Paris Writers Workshop, writers in Paris