Flâneries in Paris: Explore the Old Temple District in the Marais

This is the third in a series of walking tours highlighting the sites and stories of diverse districts of Paris.

The temple mentioned in so many street names in the third arrondissement – Rue du Temple, Rue Vieille du Temple, Rue du Faubourg du Temple – is no longer there. But I had a feeling that if I took a walk from the Temple metro station, I would find traces of it. And so it proved. I was surprised how many other historical references are hidden in this quiet little area, only three stops north of the Hôtel de Ville, yet not sought out by many tourists.

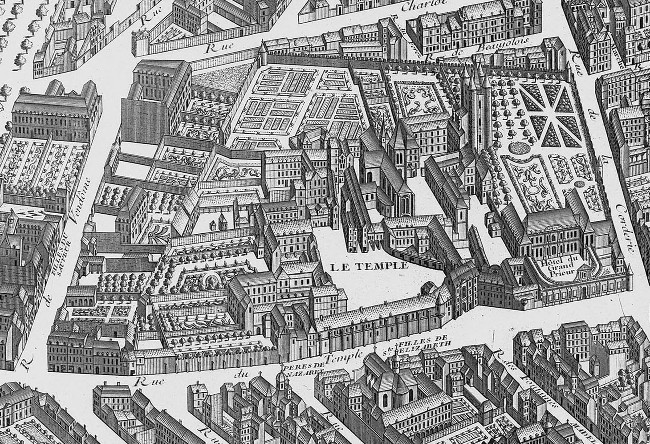

Towers of the original fortress built by the Knights Templar. Public domain

The original “Temple” was a 12th-century fortress built for the Knights of the Templar, a religious order whose exploits protecting pilgrims on their way to Jerusalem had made them very wealthy. Around it, as they prospered, grew up an area known as the “ville dans la ville” (town within the town), where several thousand people farmed and built a church, monastery and tower to house the treasure of the kings of France. By the early 1300s, King Philip the Fair, heavily in debt to the Templars and frightened by their wealth and power, disbanded the order and the area was left to fall into ruin.

Miniature from the Hours of Étienne Chevalier with the Temple in the background. Public domain.

When I climbed the steps out of the Temple metro station, the first thing I saw was Marianne, the huge statue rising up in the middle of Place de la République, erected on the 90th anniversary of the French Revolution as a “monument to the French Republic.” I planned to head the opposite way, down Rue du Temple, but was later to discover that there is a historical link between the two stories: the tower built by the Knights Templar and the demise of the French monarchy during the revolution.

The Square du Temple. Wikimedia Commons

A short walk up the Rue du Temple brought me to the lovely little Square du Temple, set up in 1857, one of 24 garden squares planned by Baron Haussmann in the redesign of the city which also brought the new wide boulevards and the Paris Opera House. The pond, trees and seating areas cover the area where the Temple once was. Today it is a family park, somewhere to exhaust your toddlers on the adventure playground, try out the table tennis tables or, if the bandstand is in use, enjoy a little music. It’s also a place to remember the families shattered by politics, war and persecution in the 1940s.

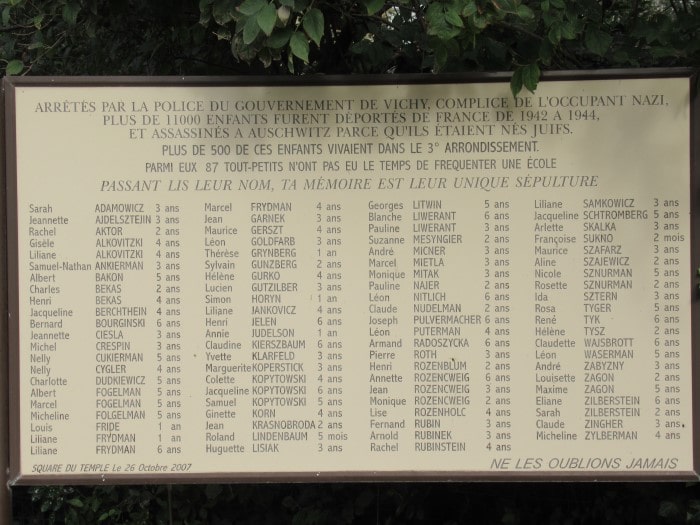

Memorial plaque in the square. © Marian Jones

Right in the middle, a large information panel, erected in 2007, remembers the 500 children from the third arrondissement deported to Auschwitz. Older children’s names are recorded outside the schools they attended, but those of the under-5s who, says the sign, “never got to go to school,” are here and the alphabetical list is heart-breaking. From Sarah Adamowicz, aged 3, to Micheline Zylberman, aged 4, there are 87 children. Little Simon Horyn was only 1. I imagine that Annette, Jean and Monique Rosencweig, aged 6, 3 and 2, were brother and sisters. And then there is Liliane Samkowicz, aged 3, who shares a Christian name with my own 3-year-old granddaughter. They were, explains the sign, “assassinated because they had been born Jewish.” And what can you possibly add, except the last line of the sign, a plea that they should never be forgotten: “Ne les oublions jamais.” The poignancy of reading it in a park full of gleeful children, getting on with the business of childhood by playing noisily together, was not lost on me.

Jean-François Garneray (1755-1837). “Louis XVI au Temple, vers 1786”. Huile sur toile, 1814. Paris, Musée Carnavalet.

I crossed the park to the far exit and found the town hall – la mairie – where display panels explain that this is the site of the 12th-century temple where a dungeon was used to imprison Louis XVI, his queen Marie Antoinette, and their children after their arrest on August 13th, 1792. Louis was taken from here to his execution; Marie-Antoinette was transferred to the Conciergerie for her trial, and their 10-year-old son, Louis Charles, died here in June 1795. The sickly child had been kept here, largely neglected, for over two years after the death of his parents. The outline of the dungeon where the family was imprisoned is marked out on the road: a reminder, whatever your views on the revolution, of a family tragedy.

Historical Louis XVI plaque © Marian Jones

Napoleon, keen to remove all traces of royalty, ordered the demolition of the remains of the fortress in 1808 and a market sprang up. In 1860 Baron Haussmann decided to create a new stylish market building, a monumental metal structure with facades of glass and brick housing four market halls, each specializing in different goods. People flocked there to buy carpets and household goods and by the 1950s it was a thriving second-hand clothing market. By the 1980s it was threatened with closure, a victim to the supermarkets, but protests against losing this iconic, 19th-century industrial building led to major renovations and today the Carreau du Temple is a thriving multi-use center. Inside you will find a 250-seat auditorium with a thriving cultural program, sports facilities, shops and cafes.

The Carreau du Temple. Photo: Kasia Dietz

In the nearby Rue de Bretagne, I discovered a foodie haven, a whole cluster of specialist shops like Jean Hévin’s chocolaterie, with its tempting array of over 40 different chocolates and truffles, lovingly displayed like jewels in a high-end store in the Place Vendôme. The Charcuterie Maison Vérot had been there since 1930, the sign for the Fromager Affineur Jouannoul stressed in the word “affineur” that they are specialists who age the cheese themselves. Whether I wanted to choose a little morsel for lunch or to take a way a carefully selected platter for an evening with friends, they were happy to oblige. The seasonal produce spread outside the Jardin des Délices was enticing too: more mushrooms than I could ever name – cèpes, girolles, chanterelles, shitake – and signs promising Le Meilleur de la Forêt, the best from the forest.

Produce at the Jardin des Délices. © Marian Jones

I was glad I already knew about the Marché des Enfants Rouges because the sign over its entrance, a tiny alleyway off Rue de Bretagne, was rather lackluster. But inside I found a jostling array of food stalls and take-away stands; in fact, this is the oldest covered food market in Paris. It is named after the Hospice des Enfants Rouges, a home for orphans and street children originally founded in the 1530s. It is both a reminder of unhappy lives and of those who tried to help by setting up the first institution in Paris for children with no family of their own. The children wore red coats, so were known as “Les Enfants Rouges” and the name still survives today.

Fish sold at the Marché des Enfants Rouges. © Marian Jones

Here too was produce a-plenty: fresh fish on piles of ice, teetering stacks of vegetables, cheeses from “la petite ferme à Inès.” Inès had gathered an enormous variety of cheeses in her stall; some I knew – Gruyère, Munster, Raclette fumée – and many were new to me, such as Vache des Pyrénées, Tome de Savoie and Tome de Chèvre à l’Ortie, that last one being flavored with nettles. There were take-away food stands from all over the globe. A Moroccan stall, with its mosaic tile backdrop and tagine pots, the brightly colored Corrosol Paria, offering afro-caribbean cuisine, veggie stalls, Japanese Bento boxes, and rustic burgers labeled “burgers-fermier.” Many had a small table or two crammed alongside; all were happy to make up a package to take away.

Cheese at the Marché des Enfants Rouges. Photo credit: Marian Jones

I bought a little picnic to enjoy on a bench in the Square du Temple on my way back to the metro. It was a chance to reflect on all I had seen. Most of all, I thought about the children whose stories I had heard: little Louis-Charles in the dungeon; the Enfants Rouges, so dependent on the charity of others; and the Jewish toddlers who never grew up to bring their children and grandchildren here and tell them stories of long ago.

Lead photo credit : The Temple area in 1734 - detail of the Turgot map of Paris. Public domain.

More in Flâneries in Paris, history, temple

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY