Montmartre — Did You Say Plaster of…Paris ?

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Montmartre quarry and tile roofs in 1826.

Sitting on Swiss Cheese

There is a saying here in France that goes “There is more of Montmartre in Paris, than Paris in Montmartre”. What the Parisians really mean by that is that much of their hill, that keeps sliding downwards today, helped build the city spread out below the Basilica of Sacré Coeur.

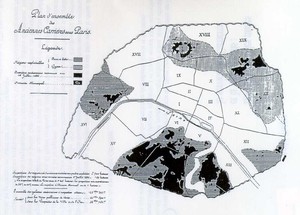

Overview of the quarries beneath Paris

Gypsum is a white cristal-like mineral used to make certain paints, plaster of Paris and even the chalk we sometimes, if rarely, still use in the classroom. The mineral is extrated in blocks, cooked in kilns, ground into a fine white powder and placed in sacks. When mixed with water, the powder heats up and once again becomes plaster. One of the purest plasters in the world comes from in and around Paris. For almost two thousand years the two hills on the right bank, Montmartre and Menilmontant (Belleville), were the hub for plaster of Paris.

Adobe tiles and frescos on plaster, the Cluny baths, 1st – 4th century AD

Plaster of Paris is so resistant to wind and rain that from 500 to 900 AD the Franks made almost all of their Mervingian sarcophaguses from molded Montmartre plaster. The only problem with natural gypsum is that it disolves easily, making local water undrinkable. The Romans were forced to bring in their water both for drinking and for the city’s Roman baths. Unfortunately, almost nothing remains today of the original Roman aquaduc leading into Paris from the Biève river. The 77 arcade Vanne aqueduc south of Paris only dates back to the 19th century. The water it carries does, however, start off just a few kilometers away, here in Northern Burgundy, and still furnishes the XVI arrondissement, where I lived for 10 years, with most of its water.

Former entry to the Montmartre quarry, Louise Michel Square at the end of rue Ronsard

In its christilline form the Romans used gypsum to replace glass, but, when they started extracting their plaster, they also came upon adobe deposits they could use both as mortar to fix their building blocks and bake into those red, terracotta flooring tiles we still see commonly in France, called “carreaux” and the red roofing tiles called “tuiles”. Just in case you didn’t know, a “tuilerie” is a place that produces such tiles. The Tuileries gardens actually derived their name from a tile-making factory built there in 1372 and torn down in 1564, when Catherine de Medici replaced it with a palace. You can see a map of the Montmartre quarries dating back to 1672 here http://troglos.free.fr/dossiers_paris_ile_de_france/dossier_carrieres_paris/extraction_gypse/dossier.html

The quarry crater would become the Buttes de Chaumont lake

A tale of two…hills

Actually two major quarries furnished plaster of Paris to the city. The Belleville district was still outside of Paris in the early 1800s, until Napoleon III decided to renovate the capital and annexed Menilmontant. In addition to plaster of Paris, Belleville’s “ Carrières d’Amérique” quarries also furnished Paris with millstone, a strong, porous brick-like stone renowned for its ability to sharpen tools and to insulate walls.

Like many houses, Montmartre’s St Genevieve of the Quarries church is made of millstone

If some 70% of the plaster used in France today still comes the Paris bassin, the gypsum quarries inside the city have vanished. In 1852 Menilmontant’s quarry was turned into a vast park, today’s Buttes de Chaumot gardens. The immense crater left behind by the quarry was converted into the gardens’ 3.5 acre lake. A decade later, in 1862, Montmartre’s main quarry became the Montmartre cemetary. A plaque in Montmartres rue du Renard and a “grotto” in the Buttes de Chaumont gardens point to the former quarry entrances.

Montmartre, Rue des martyrs, June 2001, the quarry is less than 1 meter below

But, besides fouling up the city’s water, gypsum’s “permiabilty” causes another problem that plagues the city to this day. Basically it boils down to the way the mines were created in the first place. Dynamite was often used to open new tunnels and walls were simply left standing support the mine without other reenforcement added. The city has volontarly caved in the thewalls and ceilings and filled, as it could, the cavities by injecting cement. Despite their efforts, underground runoff in Montmartre and Bellville makes it virtually impossible nowadays to properly consolidate the foundations of some 100,000 buildings. Since 1853 the city’s engineers have carried out close non-stop inspections, but Emilie Poulain’s neighbours know all too well that they are incessantly “sitting” on Swiss cheese.

History sources:

History of the Buttes de Chaumont quarries

Dealing with abandoned quarry sites

Photo credits:

More in Montmartre, Paris, Paris sightseeing, plaster of Paris, sacre coeur