What’s in a Name? The Surprising Etymology of Paris Neighborhoods

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

By 1860, there were 20 arrondissements in Paris and historically each contained four administrative areas. Sometimes the names of these quartiers still rise to the surface of maps both paper and online.

Some of these quartiers are named for saints, some are named for the parish church, others are named for their distinguished inhabitants. Some are the faubourgs, the false boroughs of Paris standing unbelievably on what was once the periphery of the city. Terminology reveals that actual buildings — follies, hospitals, and hôtels particuliers — were once located in the neighborhood. Others have puzzling or misleading names buried under piles of history. Here are some place names on the Paris map that have surprising origins.

Télégraphe is a small neighborhood that sometimes shows on Paris maps in the 20th arrondissement. Its name comes from the optical telegraph invented by the scientist Claude Chappe. To jaded 21st-century eyes, the optical telegraph is unbelievably whimsical. A line of stations or towers would display signals, like semaphore, to relay messages. Using telescopes, operators would watch each other for the special codes. This rudimentary innovation was first tested by Chappe on July 12, 1793 on the heights of Ménilmontant. Not only did the telegraph connect Ménilmontant with towns in the Val-d’Oise, he also built a tactical line between Paris and Lille.

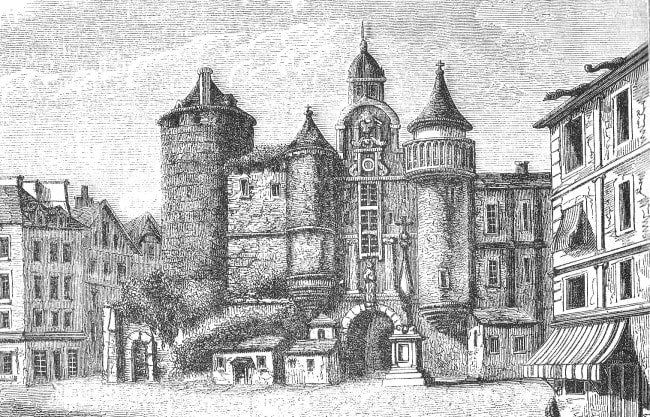

Grand châtelet (C) Public Domain, Wikimedia

Le Châtelet area takes its name from the ancient French term referring to a small castle or stronghold, usually guarding a bridge or an approach into a city. In this case, it’s the Grande Châtelet fortress, a gatehouse guarding the northern end of a bridge near the present-day Pont au Change. The Grand Châtelet was a wooden tower built in 1130 on the order of Louis VI. Louis XIV had a stronger stone structure built which housed a court and some prison cells. It was demolished during the reign of Napoleon between 1802 and 1810.

Combat des animaux (C) Gallica BNF

The Combat neighborhood in the 19th arrondissement is named for the animal fighting – combat des animaux – which went on in this district. The following is quote taken from an 1852 book called Pencillings by the Way by Nathaniel Parker Willis. “My curiosity led me to a strange scene today. I observed for some time among the affiches upon the walls, an advertisement of an exhibition of ‘fighting animals.’ I am disposed to see almost any sight once.” Willis found that “The Combat des Animaux is in one of the most obscure suburbs.” This was recorded in the days before Paris was arranged in arrondissements and when Willis eventually found the location (today the oval Place du Colonel Fabien), he saw a narrow alley lined with stone kennels each housing the most ferocious dog he had ever seen. In total, there were about 200 dogs condemned to fight. From 1771 to 1833 dogs, bulls, bears, wild boars and other animals were forced to fight to death.

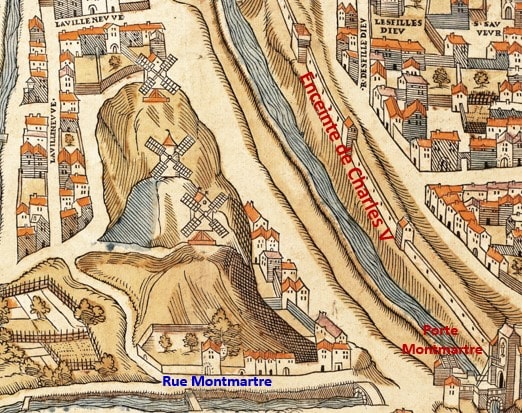

Bonne Nouvelle. 1550 map by Truschet et Hoyaux. (C) Public Domain, Wikimedia

The neighboring areas Bonne-Nouvelle and Montorgeuil in the second arrondissement share a history steeped in garbage. A heap of refuse, which began in the 1300s, was originally created from the dirt excavated during the building of the retaining wall of Charles V. The amount of rubbish, sludge and goo that the local inhabitants flung onto the heap was so alarming that it formed its own hill. Butte Bonne-Nouvelle was first named Mons Superbus, Superb Mount. In the 15th century, it was ironically dubbed Mont-Orgeuil – proud mount. Farm plots, even windmills topped the hill. Based on excavations carried out in 1824, this urban dump was as high as 16 meters.

An illustration from Joseph Lauthier’s Nouvelles Règles pour le jeu de mail (1717). Wikimedia commons

Quartier le Mail most likely gets its name from the croquet-like game, Paille-Maille or Jeu de Mail, that was played during the reign of Henri II (the king was an excellent player). The playing field behind the Palais Royal later became the Rue du Mail and the name was then adopted for the district.

In the third arrondissement, the Enfants-Rouges neighborhood takes its name from the Hospice des Enfants-Rouges. Founded in 1536 by Marguerite de Valois, the sister of François I, it was both an orphanage and a hospital. Dressed in red as a symbol of Christian charity, the children were nicknamed the Enfants-Rouges. The orphanage closed in 1772, but the name lives on in the Marché des Enfants-Rouges.

Vegetables for sale at the Marché des Enfants Rouges. Photo credit: Mx. Granger / Wikimedia commons

In the same arrondissement is Temple, but no temple remains here. The area gets its name from the Knights Templar who owned most of the land around the Marais. The knights drained their swampy land and behind an 8-meter wall enclosed over 130 hectares for themselves. The enclos du temple was an independent state within the walls of Paris. The resentful King Philip IV got fed up, dissolved the order in 1313, and Jacques de Molay, grand master of the order, was burned at the stake in what is now the Square du Vert-Galant on the Île de la Cité.

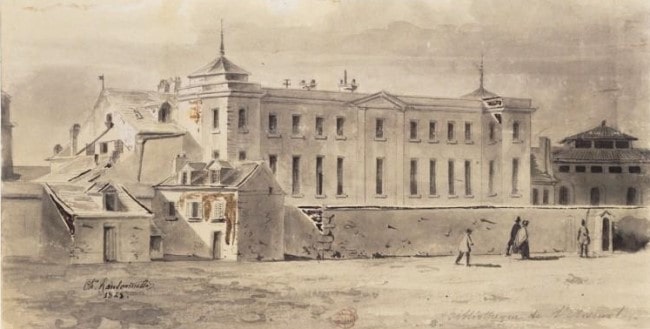

The triangular area in fourth arrondissement called Arsenal was just that, a weapons storehouse. In 1757, the bailiff of the artillery created a library within its walls. The Arsenal library was one of the largest and most important in the city of Paris during the 19th century. During the Romantic era, one of the most reputable salons of Paris was held at the Arsenal Library and including luminaries like the writers Balzac, Hugo and Dumas and the painter Delacroix. Today the Arsenal Library hold more than a million volumes.

Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal by Charles Ransonnette, 1848. Public Domain

The name of the neighborhood Saint-Victor derives from the Abbey of Saint Victor, which in turn pays tribute to a Roman linguist named Gaius Marius Victorius. The 12th-century abbey destroyed in 1798 was known at that time to be one of the most important centers of intellectual life in the medieval West. The buildings later became a wine market, the Halle aux vins, and the Faculty of Sciences of the University of Paris stands there now.

Though not a quarter, but a street, the prettily named Cherche-Midi means to “search for midday” and derives from a sign once located on the street. The sign represented a sundial decorated with people searching for noon at two in the afternoon. The proverb “cherchant midi à quatorze heures” means to make easy things complicated.

Courtesy of the Monnaie de Paris. Photo: Gilles Targat

Monnaie is the home of France’s longest standing institution and the oldest enterprise in the world, the Monnaie de Paris. The mint was officially founded in 864 when Charles the Bald decreed the creation of a coining workshop in Paris. It has been in continuous operation in one form or another since it opened.

Gros-Caillou means big stone, probably the stone used since medieval days to divide the parishes of Sainte-Geneviève and Saint-Germain-des-Prés. Inhabitants of this area were recorded using this term back as far as 1510.

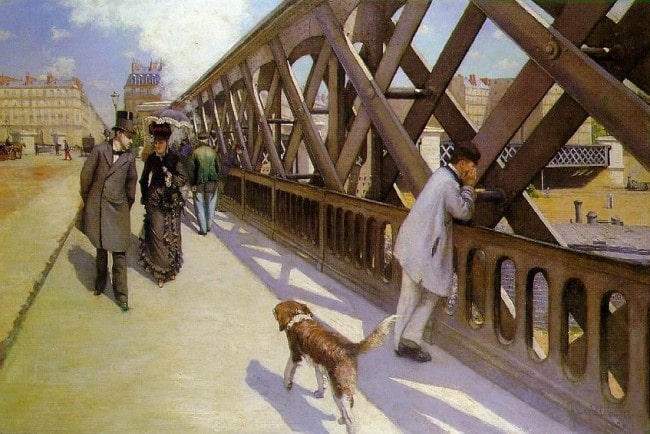

Le Pont de l’Europe by Gustave Caillebotte, 1876.

In Greek mythology, the Champs-Élysées, aka the Elysian fields, were an eternal paradise reserved in the after-life for heroes and virtuous souls. This major Parisian thoroughfare was built in 1674 by the famed royal architect André Le Nôtre. The extension passed over a swampy bog and it’s not known if the moniker was meant to be a joke.

The Europe neighborhood is centered around the Place de l’Europe, where there is a concentric star pattern of streets named after European towns: rue des Londres, rue de Madrid, rue de Vienne, rue de Rome, rue de Constantinople, to name a few. The Place de l’Europe straddles the rail lines coming in and out of Gare Saint Lazare, adding to the area’s international vibe. Two land speculators, Hagerman and Mignon, designed the star-like radius, which is a similar plan to the etoile surrounding the Arc de Triomphe.

Hopital des Quinze-Vingt in the 12th. (C) Mbzt, Wikimedia commons

The Nouvelle Athènes area developed in the 1820s and it’s called New Athens due to the numerous neoclassical buildings which flourished here, featuring large porches and porticos, cast-iron balconies and intricate moldings and friezes. The artists and intellectuals of the Romantic movement, Sand, Chopin, and Liszt, gathered here. The vanguard of the Impressionists met in a café bearing the same name.

The Hôpital Saint-Louis district owes its name to the Saint-Louis Hospital, built at the beginning of the 17th century on the orders of Henri IV to deal with the capital’s plague epidemic. It is named after King Louis IX, the Capetian king who died in the Crusades in 1270. Another hospital connection is found within the 12th arrondissement. The Quinze-Vingts district which takes its name from the Quinze-Vingts, named for the 300 (quinze x vingts) beds it boasted when first built in the 13th century. The hospital still stands and is an ophthalmology hospital located at 28 Rue Charenton.

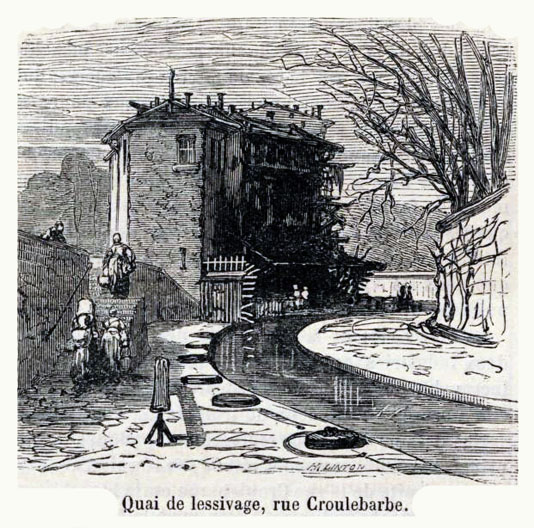

The rue Croulebarbe and the banks of the Bièvre in 1865.

La Roquette sounds sort of fun but that’s debatable. Not only was it home to the 17th-century Roquette convent and women’s hospital, but from the 1830s until 1974, the La Roquette district housed two prisons: La Grande Roquette and La Petite Roquette. Also debatable is the origin of the name Roquette. The name could come from a small flower, or from the word rocher, or the name of a manor belonging to the House of Valois variably named Petite Roche or Rochette.

In the 13th arrondissement, the Croulebarbe quarter takes its name from the 13th-century resident Jean Croulebarbe, who owned vineyards and mills on these lands. The Maison Blanche district takes its name from a little settlement where Maison Blanche metro is now. The village itself was named after the Maison Blanche inn. The Salpêtrière hospital is the focus of the Salpêtrière neighborhood, but the gunpowder storehouse built by Louis XIII is the reason behind the name. Saltpeter is an explosive used in gunpowder. The neighboring district of La Gare takes its name from the river depot that was built there at the end of the reign of Louis XV and not from the presence of Gare d’Austerlitz.

Place Denfert-Rochereau. Credit: Mbzt, Wikimedia commons.

Denfert-Rochereau… a play on words or just a splendid coincidence? The Place Denfert-Rochereau was named in 1879 for a courageous war hero with the grandiose nickname, “The Lion of Belfort.” Besides the over-the-top lion statue, the entrance to the Catacombs of Paris is also found in the Square. The area was once called the Place d’Enfer (Place of Hell) and Denfert and d’Enfer are pronounced exactly the same. The city administrators managed to pay tribute to a war hero while keeping Paris’s traditional history.

The district known as Les Gobelins is named for the owners of the renowned dye and textile workshop, Manufacture des Gobelins, whose family name is now synonymous with fine tapestry. They gained fame supplying the French court as far back as the 1600s. The etymology of their surname does in fact reveal that it means gnome or evil sprite.

Petit-Montrouge owes its name to the nearby commune of Montrouge. When Montrouge was annexed to Paris in 1860, it was divided two parts, the Grand-Montrouge, which is now simply Montrouge, just outside the Boulevard Périphérique, and Petit-Montrouge. Meaning red mountain, there doesn’t seem to be any discernable change in elevation here but there were quarries in the area and the ground around them was known to be reddish.

Rear view in 1830 of the Gobelins Manufactory, adjoining the river Bièvre. Credit: Gallica BNF

Another location name that indicates a hill where there is none is Montparnasse itself. Named after Mount Parnassus in Greece, mythical home of the Gods, the only hill here was a mountain of rocky debris and detritus piled high during the excavation of the Paris Catacombs in the 18th century. Remnants from the area’s stone quarries further served to add to the piles. Arrogant students from the nearby Sorbonne came here, like the Grecian deities of yore, to recite poetry and spout philosophy. They ironically christened this unstable pile of rocks Montparnasse.

And then there’s Parc Montsouris – Mouse Mountain Park. The name of the park could come from and old 18th-century windmill which stood not far from the crossroads of rue d’Alesia and rue de la Tombe-Issoire. Moque-souris was a common name for French windmills whose owners dared the mice to come inside. Instead of mice, it might be a giant that Parc Montsouris is named after. The resident of the Tombe-Issoire was a colossal landowner who was murdered on this spot. His name was variously thought to be Issoire, Issaure, or Ysore; perhaps the mouths of many generations turned his name to Souris.

Rothschild’s Château and OECD headquarters, at Château de la Muette, Paris in 2019. The old chateau was demolished to make room for it. Photo credit: MySociety / Wikimedia commons

Attached to Paris in 1860, the district of La Muette is named after the Chateau de la Muette, a splendid house on the edge of the Bois de Boulogne, given to the future Queen Margot by Charles IX. The etymology of muette is not certain but it more likely means “place for a pack of deerhounds” rather than the contemporary translation the mute, as the palace was used as a hunting lodge.

The Épinettes neighborhood in the 17th arrondissement was most likely named after a local variety of grape called épinette blanche, a synonym for Pinot Blanc. Another hypothesis takes into account that épinette also means piney,,or prickly, and the area perhaps took its name from the brambles that originally grew on its land. In any case, it was first mentioned back to 1693.

The rue de Chartres in the Goutte d’Or. Photo credit: Benchaum / Wikimedia commons

The drop of gold. The Goutte-d’Or neighborhood takes its name from the golden-white wine produced in the small hamlet of La Goutte-d’Or, which is now part of the Montmartre area.

With records dating back to the 13th century, it’s hard to believe that Ternes was once a modest wooded area that French royalty used for hunting. The village centered around a fortified residence of the same name. The town’s name probably came from the Latin term “villa externa” – outward village, which, over time, became Ternes.

Parc des Buttes-Chaumont by Traktorminze/ Wikipedia

The Grandes- Carrières neighborhood takes its name from the old gypsum quarries – carrières – which provided the materials needed to produce plaster of Paris. Remains of these quarries have been transformed into Montmartre Cemetery or Square Louise-Michel at the foot of Sacré-Cœur.

Due to these quarries, the area around Montmartre and Buttes-Chaumont were once referred to as the Gruyère Parisian. The Quartier d’Amérique adds to this district’s Swiss-cheese foundation. This area takes its name from the Carrières d’Amerique, American quarries, where gypsum was extracted until 1873 and exported to the United States. The urban legend goes that this plaster was used for the construction of the White House, but the rumor can’t be verified. The plaster was crucial for domestic construction in the age of Haussmannization. The pretty, treed area is also known as the Quartier de Mouzaïa, named after the Algerian mountain pass where the French army fought in 1839.

Lead photo credit : Chappe's semaphore in Paris. 19th-century painting. Author unknown. Public Domain, Wikimedia

More in Distric, Historians, history, Names, Paris

REPLY