See Now at the Musée d’Orsay: Van Gogh in Auvers-sur-Oise

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Despite the timed tickets, there was a sizeable line at the Musée d’Orsay winding its way toward the exhibition Van Gogh in Auvers-sur-Oise: The Final Months. A life-sized photo reproduction of 19th-century Auvers-sur-Oise introduced the gallery; fitting, for this town is where museum-goers will be for the length of their ticket.

The Musée d’Orsay has mounted an exhibition focusing on the last months of Vincent Van Gogh’s life. On May 20th, 1890, Van Gogh moved to Auvers-sur-Oise, a village about 30k north of Paris. Living in the south of France, Van Gogh had been suffering from presumed bouts of insanity. On his return to Paris, Vincent’s brother, Theo, quickly arranged to have Vincent move to Auvers-sur-Oise under the care of Dr. Paul Gachet, a doctor specializing in depression. Gachet knew depression first-hand and took Vincent under his wing.

The exhibition is subtitled The Final Months because Van Gogh would take his own life in Auvers-sur-Oise, succumbing to a gunshot wound on July 29, 1890 in his rented room at the Auberge Ravoux. Vacillating between confidence and despair in the 70 days he spent in Auvers-sur-Oise, Van Gogh would produce 74 paintings and 33 drawings. The exhibit brings together a majority of these works, all created in Auvers, except one.

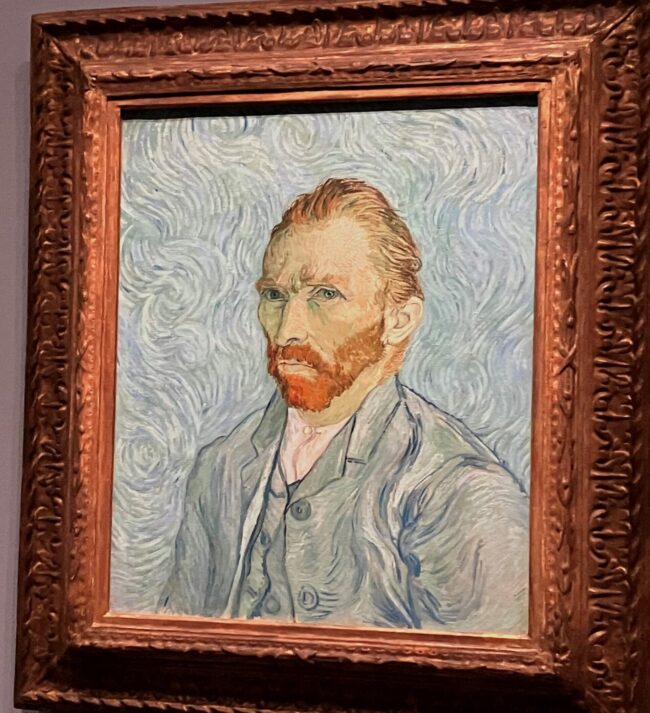

The exception is the remarkable painting created during Van Gogh’s hospital stay in Saint-Remy; his second-to-last and most famous self-portrait. It’s a powerful image strong enough to stare down the thousands that stand in the same footsteps as the artist at his easel. Vincent bundled up the painting and took it to Auvers-sur-Oise to show Dr Gachet as an example of his work.

Vincent Van Gogh, Self Portrait, 1889. Exhibit photo: Hazel Smith

“I’ve found in Dr Gachet a ready-made friend and something like a new brother would be – so much do we resemble each other, physically and morally too.” – June 5th, 1890.

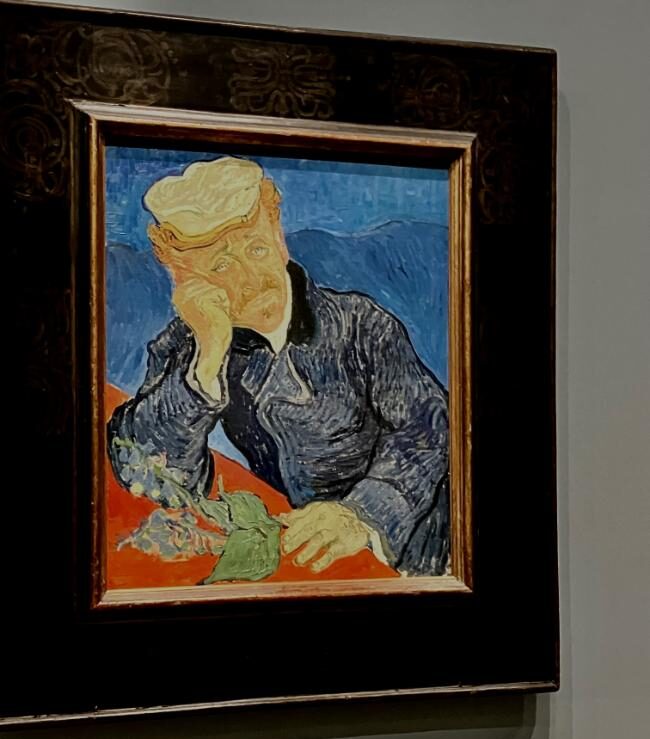

Idle hands find devil’s work, and Dr. Gachet knew that Vincent would have to throw himself fully into his work to stave off depression. In a room of melancholy blue, we get to know the doctor. Gachet wrote his medical thesis on melancholia – who better to entrust with Vincent’s mental health? However, Vincent thought Gachet was suffering as badly from nervous trouble as he was. In Gachet, Vincent saw his doppelganger.

In this image of Doctor Gachet, painted in early June of 1890, we can see the resigned posture of depression that the doctor shared with his patient.

Portrait of Dr. Gachet, 1890. Vincent Van Gogh. Exhibit photo: Hazel Smith

At Gachet’s, Van Gogh had the opportunity to create his one and only etching, included in the exhibition. They printed the engraving on Gachet’s own press. Some of Gachet’s own works are included as well.

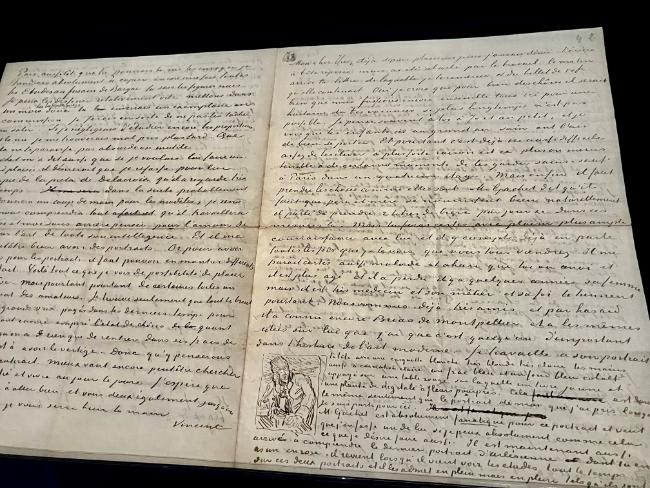

An absolute “shiver up the back of the neck” is the letter that Vincent wrote to Theo, dated June 3rd, 1890, about his new friend, complete with a tiny cartoon of the painting of Gachet he had just completed. The Van Gogh letters are available in facsimile form online and in print, but to see a letter from Vincent’s own pen was very moving.

Letter from Vincent Van Gogh to his brother Theo, June 3, 1890. Photo: Hazel Smith

In the exhibition, one thoroughly discovers Auvers-sur-Oise, then a town of about 2000 inhabitants. The village is much the same today. Vincent depicted it through myriad colors, and techniques perhaps not readily appreciated. He was instantly charmed by it. “There’s a lot of well-being in the air,” he stated. Most of his paintings were completed within a small radius of his new lodgings at the Auberge Ravoux. The subjects of the first paintings he put down on canvas were of cows, blossoms, and colorful thatched cottages that reminded him of his home in the Netherlands.

Houses in Auvers, Vincent Van Gogh, 1890. Photo by Hazel Smith

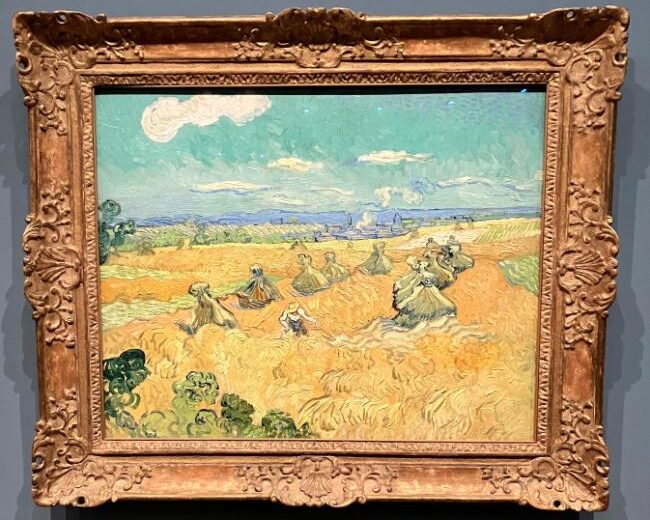

My favorite of Van Gogh’s fields is this one in which farmers’ wheat stacks lift one’s eyes to amazing skies of three or more blues with a touch of inexplicable, but perfect, violet.

Wheatfield with Sheaves and Reaper, Vincent Van Gogh, 1890. Photo by Hazel Smith

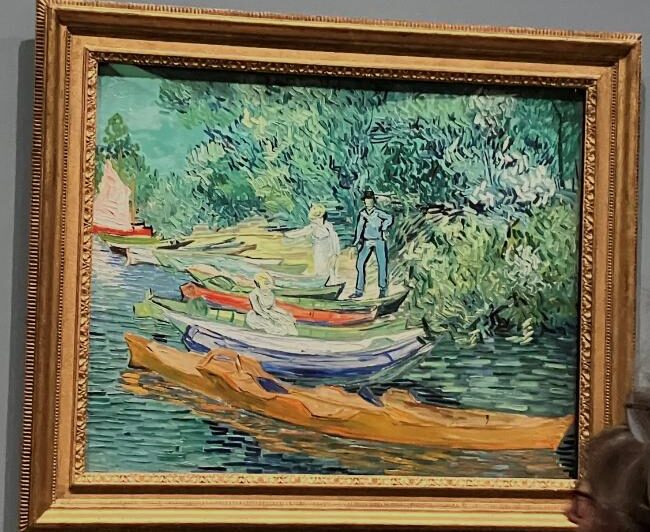

What’s obvious from the exhibit, which an interpretive panel indicating the locations of his work confirms, is that Vincent did not dwell on the leisurely life by the River Oise at all. Therefore, the Bord de l’Oise with its array of colorful boats on the river’s bank is a wonderful, jolly look at an aspect of Auvers-sur-Oise largely undiscovered by Vincent.

Bord de l’Oise, Vincent Van Gogh, July 1890. Photo: Hazel Smith

The lighting created by the exhibit’s design team is spectacular. The paintings seem to glow from within and the textures on Van Gogh’s canvases can be fully appreciated.

Maison à Auvers is a good example of this. Most likely fellow painter Daubigny’s garden, viewers can all but feel the tactility of the garden’s pebbles and grass. Flowers sparkle in quickly applied dots; the colors in the stippled lawn and pavement are perhaps not so obvious in nature.

Perhaps this is part of the color theory that obsessed Van Gogh. To paraphrase his entreaty to Theo in 1885, “if you find some book on color questions that is good, do be sure to send it to me.” Van Gogh believed in color theory, and the effect of primary and complementary colors against one another.

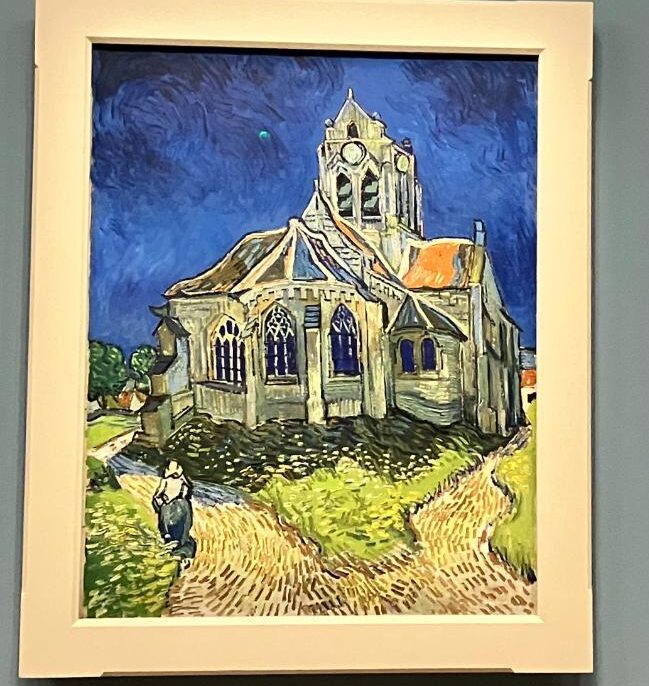

Most of the art is shown to its best advantage in large ornate frames. Nevertheless, that’s not always what Van Gogh wanted. It is startling to see the plain, almost bent frame on the Church at Auvers-sur-Oise. Van Gogh attached great importance to the framing of his paintings, and preferred them to be simple. Instructions found in the attic of Gachet’s house revealed that Van Gogh’s painting Thatched Cottages at Cordeville (unfortunately not pictured) was to be displayed in a plain frame to best emphasize the colors it surrounded. Nonetheless, the work ended up in an ornately gilded frame. Based on these instructions, other paintings in the Musée d’Orsay from the Gachet collection, including that of the church, have been outfitted with new frames to respect Vincent’s choice.

The Church at Auvers-sur-Oise, Vincent Van Gogh, 1890. Photo by Hazel Smith

One of the interpretive panels found in the gallery’s side rooms carefully examine the nature of Van Gogh’s brush strokes. The painting of the Church at Auvers-sur-Oise demonstrated the long, soft, dry lines of Vincent’s brush, which gives the edifice an anthropomorphic feel. I agree – I can hear the church sighing.

Visitors can catch their breath for a moment in one of the interpretive rooms, where one can sit in a somewhat quieter corner. The exhibition rooms were incredibly busy with viewers jostling for elbow room and Instagrammable moments. It’s busy, but it’s Van Gogh.

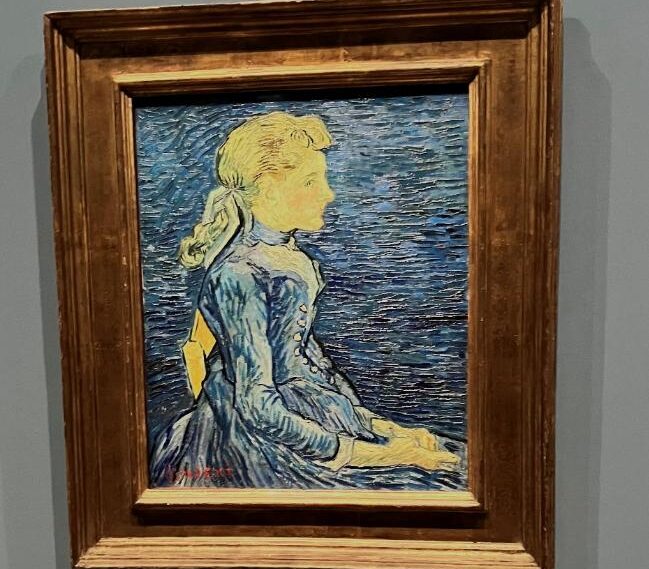

There’s an interesting wall montage of postcards of Auvers-sur-Oise from the time Van Gogh lived there, as well as a slide show featuring the town’s residents. Portraits of some of them are included in the exhibition – some naughty looking children, and the daughters of Gachet and Ravoux. Within them, he tried to capture “an indefinable eternity,” which he tried to realize with radiance itself. One painting of Ravoux’s daughter Adeline is an exercise in contrasts and almost impossible to correctly capture with a camera.

Portrait of Adeline Ravoux, Vincent Van Gogh, 1890. Photo by Hazel Smith

The dynamic, swirling, genius mess of Van Gogh’s palette is displayed in a case along with some tubes of oil paints rescued by Dr Gachet after Vincent’s death. As with his letters, it’s almost daunting to be so close to the man himself.

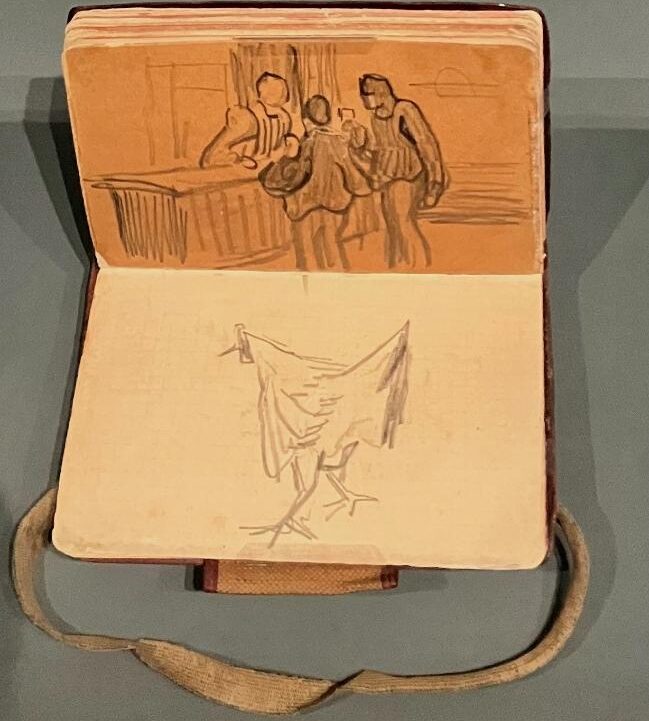

There’s a charming carnet de croquis, or sketchbook, with the pages turned to a café scene and a very humorous chicken. The book is half-filled with scribbles that I would love to see more of.

Carnet de Croquis, Vincent Van Gogh, 1890. Photo Hazel Smith

Van Gogh’s easel and oil paints. Photo: Hazel Smith

There are many graphic studies and drawings that Van Gogh completed during his time in Auvers-sur-Oise. There are strange, two-toned pen sketches with the sky blued in. The rhythmic painting Ears of Wheat takes up the whole canvas like a wallpaper of rustling grain. Slashes of rain on his work Pluie evoke the Japanese prints by Hiroshige that influenced his painting.

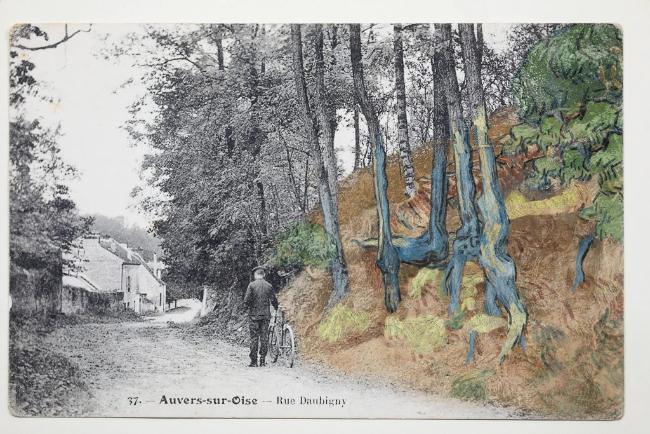

Some of Van Gogh’s paintings seem to be influenced by his colleague Gauguin, with a flat, dry, almost chalky hand. One example is Tree Roots. This painting is now thought to be Vincent’s last work, instead of Wheatfield with Crows from earlier in July. Recently a hawkeyed postcard collector noticed the exact same formation of gnarly trunks in a late 19th-century postcard as in Van Gogh’s July 1890 painting, and the location has been preserved.

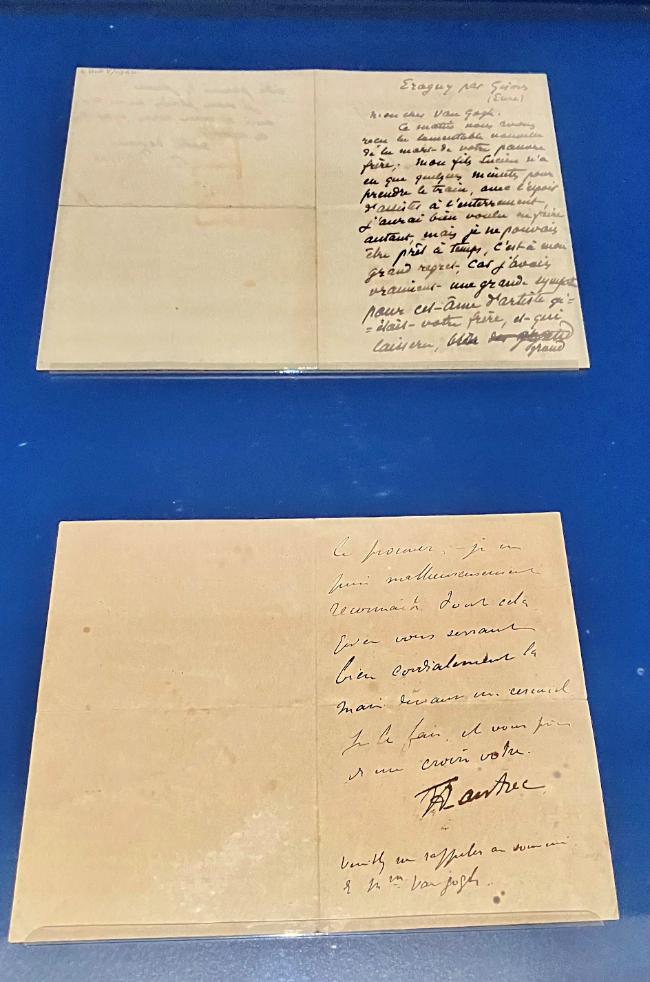

Upon Vincent’s death, Theo was inundated with letters of condolence from many well-known artists, including Monet and Toulouse-Lautrec. They contradict the myth of the accursed artist and show that Van Gogh was indeed recognized by his peers.

Letter of Condolence from Toulouse-Lautrec. Photo Hazel Smith

The exhibition winds down with a film montage, from Kirk Douglas in Lust for Life to Willem Dafoe At Eternity’s Gate. What would Vincent think of this adulation? He was a humble man who admitted that all he strived to do was to be as good as his fellow painters. But hindsight shows us that Van Gogh is still a painter without compare.

Van Gogh in Auvers-sur-Oise: The Final Months is a fantastic exhibition. It runs until February 4, 2024. Even if you have only a passing knowledge of Vincent Van Gogh, this show shouldn’t be missed.

DETAILS

Musée d’Orsay

Esplanade Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, 7th

Closed Mondays

Reservations must be made online in advance for a given time slot.

Full-price ticket: €16

Lead photo credit : Field with Poppies, Vincent Van Gogh, 1890. Photo by Hazel Smith

More in Art, museums, Van Gogh

REPLY