The Traveling Exhibition of Georgia O’Keeffe at Centre Pompidou

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

From September 8th until December 6th, the Centre Pompidou is presenting the first retrospective in France of Georgia O’Keeffe, undoubtedly one of the most important North American artists of the 20th century. O’Keeffe’s Jimson Weed/White Flower No 1, painted in 1932, sold at auction in 2014 for a staggering $44,405,000, which made it the most expensive painting sold by a woman artist in the world.

Exhibiting around 100 works, paintings, designs and photographs, this exceptional exhibition has only been possible thanks to the participation of the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum of Santa Fe, the MOMA of New York, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum of Madrid (where the exhibition started,) and private collectors who generously lent their paintings.

Georgia O’Keeffe with Matisse Sculpture © Alfred Stieglitz, Wikimedia Commons

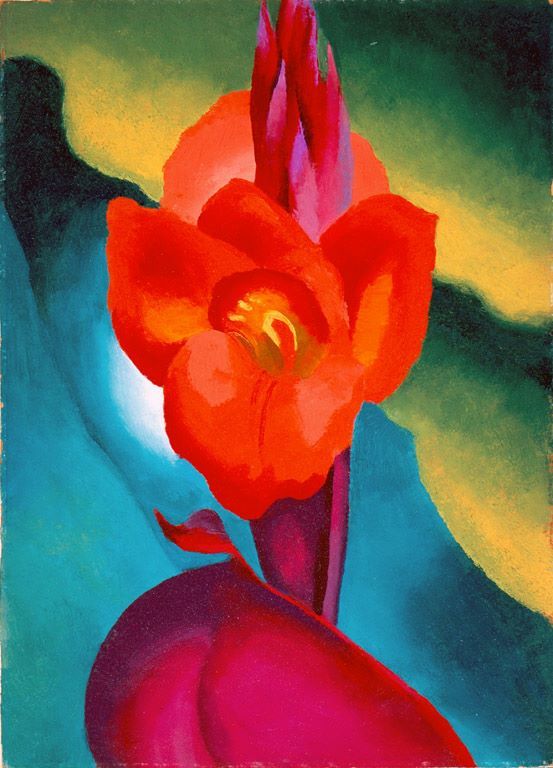

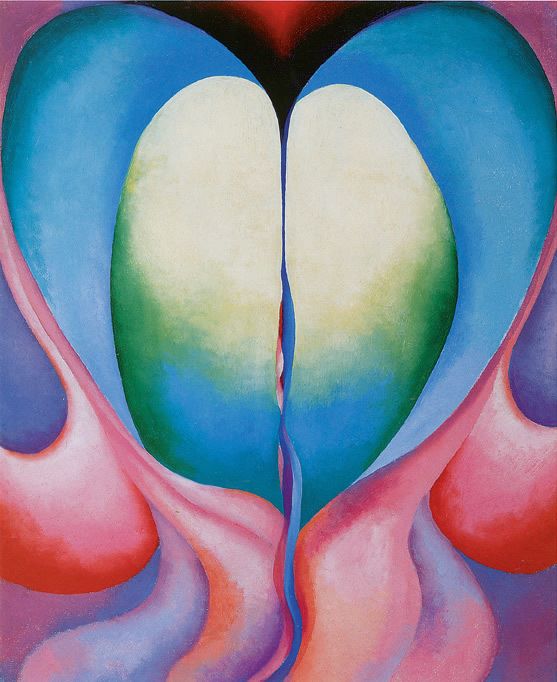

O’Keeffe, of course, is primarily known for her oversized flower paintings, and many of these including Inside Red Canna, Jimson Weed/White Flower No 1, Oriental Poppies, White Iris No 7 and Aron 1V will be displayed alongside some of her earlier abstract works, Evening Star painted in 1917 and Black Lines in 1916. The monumental, orange and yellow From the Plains 11, painted in 1954, is the second version of a painting executed in 1919, and along with Black Mesa Landscape New Mexico, painted in 1930, Rams Head, White Hollyhock Hills and Black Door with Red, all illustrate the inspiration and influence of the New Mexico landscape where O’Keeffe eventually made her home.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Red Canna, 1919

But New York came before New Mexico, and the New York skyline could not fail to inspire O’Keeffe, resulting in amongst others, New York Street with Moon and The Ritz Tower 1928, both in the exhibition.

Before New York, before New Mexico, came Wisconsin where O’Keeffe was born in 1887, the eldest of five girls in a family of seven children. O’Keeffe was the daughter of a successful farmer, trading in horses and cattle, dairy and crops. The O’Keeffe’s farmhouse, outside Sun Prairie, near Madison, looked out over vast acres of rolling farm land, high with wheat in summer, and covered in snow in winter, and O’Keeffe, as with her siblings, helped out with the horses and in the vegetable garden and in the house, cooking and sewing. O’Keeffe’s mother, Ida, was a resolutely progressive woman, determined that her girls would have as good an education as possible, and although O’Keeffe professed to have hated school and learned nothing there, private painting and drawing lessons when she was 11 left O’Keeffe in no doubt that her future was already set. She was going to be an artist.

O’Keeffe’s talent was apparent from an early age and when the family moved to Virginia in 1902 when she was 15 years old, O’Keeffe was known as “the queen of the art studios” in the private Chatham Episcopal Institute where she was a boarder.

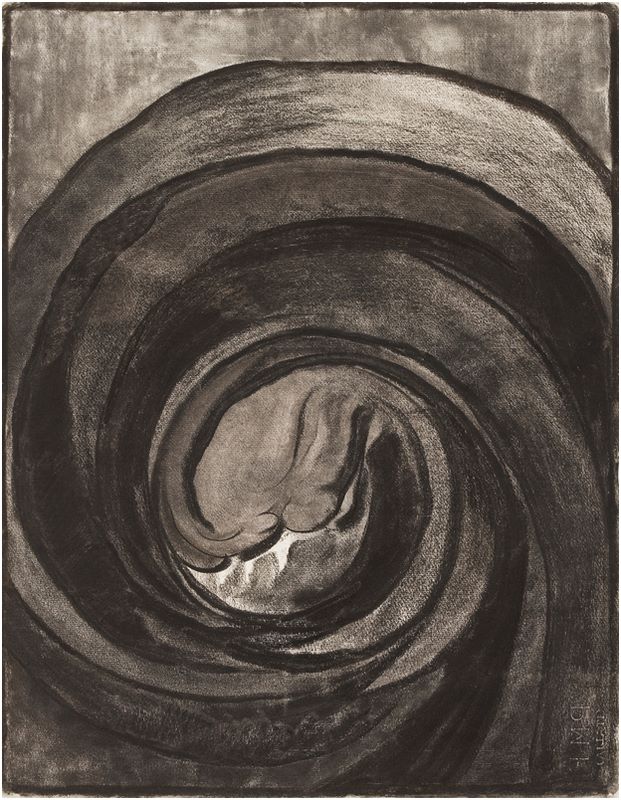

Georgia O’Keefe, No.8 Special, 1916

1905 found O’Keeffe at the Art Institute of Chicago. By the end of her first year O’Keeffe was ranked top of her class of 29 women. A bout of typhoid prevented her return to Chicago and after convalescing, O’Keeffe enrolled instead at the Students Art League in New York. Her studies there, however, were cut short in 1908 when her father’s business suffered a downturn, and O’Keeffe, to support herself, became a commercial artist before teaching in various schools and colleges in Virginia. O’Keeffe was still finding her way artistically but in 1912, she enrolled in an advanced course for school teachers at the University of Virginia. Her tutor was Alon Bement, who introduced O’Keeffe to the works of Arthur Dow. O’Keeffe was so instantly inspired by Dow, who was a radical art teacher, influenced by shape and form, color and line, and Japanese art, that O’Keeffe abandoned her previous academic ways of painting and two years later in 1914, O’Keeffe began studying under Dow himself. She had started experimenting with abstract shapes and bold charcoal drawings on large pieces of paper, and began seriously considering whether she could make it as an independent artist.

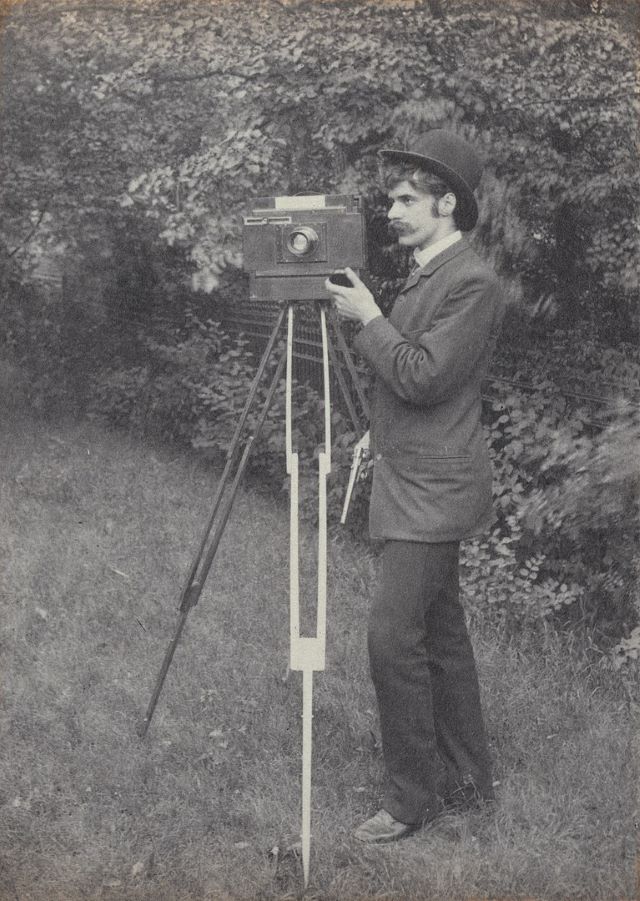

Alfred Stieglitz, self-portrait, 1886 © Public Domain

Enter Alfred Stieglitz.

Stieglitz was not only a well known photographer but also the owner of a prestigious art gallery, the 291 Gallery, on Fifth Avenue New York. Stieglitz was passionate about promoting American painters and had been the first to show works by Matisse, Rodin, Cézanne and Lautrec, giving Picasso and Rousseau their first solo U.S. exhibitions.

O’Keeffe’s friend, Anita Pollitzer, showed Stieglitz some of O’Keeffe’s drawings in 1916.

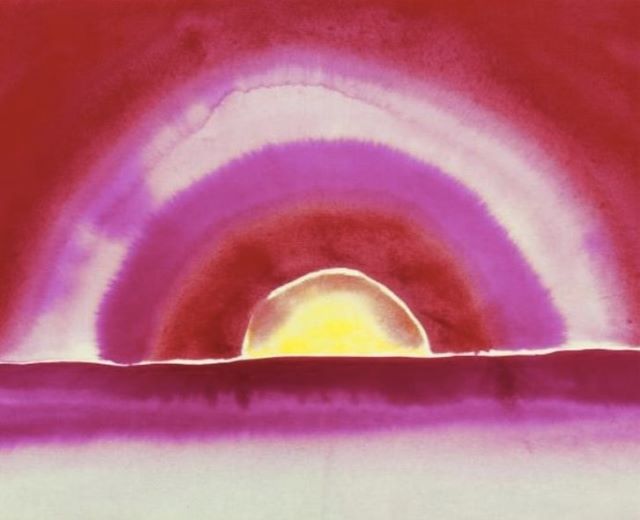

Stieglitz was blown away and without telling O’Keeffe, exhibited them in his gallery. In 1917, Stieglitz staged O’Keeffe’s first solo show. By now, O’Keeffe had embraced watercolor again, and her paintings were of vibrant sunrises, fiery sunsets, and planets.

Georgia_O’Keeffe, Sunrise, watercolor, 1916

The following year, 1918, O’Keeffe fell victim to the virulent flu that was raging across the country and Stieglitz persuaded her to come to New York to recuperate in the vacant apartment of his niece at 114 East 59th Street. Despite Stieglitz already being married, they began an affair, Stieglitz taking a series of intimate photographs of O’Keeffe. Later, this inevitably led to the supposition, one that O’Keeffe always vigorously denied, that her detailed paintings of flowers depicted female genitalia.

The couple married in 1924 and divided their time between New York and Lake George where O’Keeffe, now painting with oils, produced landscapes, lake and mountain views, close-ups of leaves and flowers, still lifes and several paintings of the old shed where she painted, one entitled, My Shanty, Lake George, 1922. But of course it was her flowers, painted on a very fine weave canvas coated with a special primer to make the surface especially smooth, that the colors subtly blended in to make her brush strokes invisible, the flowers magnified so that as in Red Canna, the painting seems almost abstract. These depictions of flowers had never been seen before.

Georgia O’Keeffe Torso by husband © Alfred Stieglitz

A visit to Taos in New Mexico in 1929 was to prove a catalyst in O’Keeffe’s life and career. (O’Keeffe would have said that they were one and the same.) She was overwhelmed by the vast scale of the landscape, the clear light and the colors of the mountains. She explored everywhere, learning to drive so she could travel even further afield. Later, when she made New Mexico her home, she would paint in her Model-A Ford. It gave her protection from the weather and the passenger seat could swivel around giving her a makeshift easel.

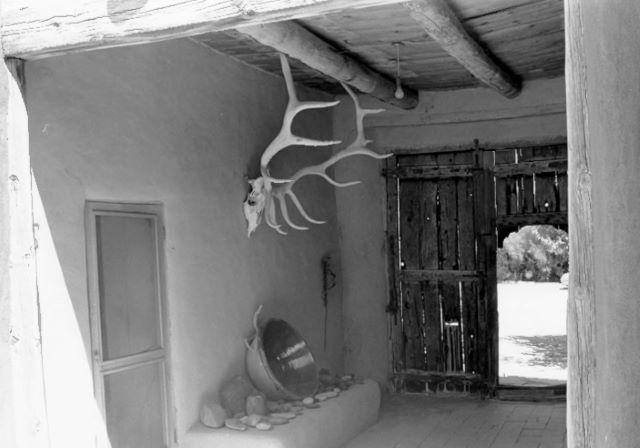

O’Keeffe’s first home in New Mexico was on Ghost Ranch in the Chama River Valley with a view of Pedernal mesa, a geological wonder of layers of dramatic colors. She had become fascinated by the dried-out animal bones scattered everywhere and had a barrel full of them transported back to New York, which she used not only for decoration in her home but also as an inspiration in her work. Ram’s Head, White Hollyhock-Hills 1935 was a classic example.

Despite Stieglitz’s infidelities, the couple stayed married. Their personal relationship may have become shaky, but O’Keeffe’s reputation was growing stronger and in 1934 The Metropolitan Museum of Art bought Black Hollyhock, Blue Larkspur. In 1938 she received an honorary doctorate from the College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, and in 1943, The Art Institute of Chicago held O’Keeffe’s first major retrospective.

Georgia O’Keeffe’s home. Wikimedia Commons

In 1946 Stieglitz died. Twenty-three years O’Keefe’s senior, he had been her unwavering supporter, promoter and husband. After three years in New York settling Stieglitz’s estate, O’Keeffe left for New Mexico for good. O’Keeffe had found another house in the small village of Abiquiu, just a few miles from Ghost Ranch. The two simple adobe buildings were converted into living accommodation and a studio with bedroom and bathroom for O’Keeffe’s personal use. With its own water supply, O’Keeffe had a large garden where she grew her own flowers and vegetables. Her house was to become the subject of many subsequent paintings, Patio with Clouds, 1956, being just one of them.

Except to go traveling – O’Keeffe adored plane journeys – she was to remain in her adobe house until her death. O’Keeffe took her first flight in 1953 when she was 64 years old. She was hooked immediately; the aerial views of clouds, rivers cutting through barren landscapes, the patterns of fields, and the majesty of mountains ignited her imagination and fueled an insatiable appetite to see the world, something as a young woman, she had not previously wanted. As an artist, this had been unusual, but O’Keeffe did not see France or Spain until she was approaching old age. She made up for lost time and by 1959 had spent two months in Peru and the Andes and three months in Asia, the Middle East and Rome.

Portrait of Georgia O’Keeffe in Abiquiu. © Carl Van Vetchen. Public Domain

And all the time O’Keeffe’s popularity was growing, her reputation in the art world was becoming unassailable, and in 1962 O’Keeffe was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

She had also become a role model for female artists. Despite her age, O’Keeffe was a strong, independent woman. Her art was everything. She had not become a house wife or mother. She was fiercely self reliant and self disciplined. She was unafraid to live in remote places, live a solitary existence for her art, the only thing that had real meaning for her. And so for O’Keeffe the tragedy that was to befall her in 1971 was the most cruel of all.

She was diagnosed with macular degeneration. She was losing her eyesight. She completed her last unaided canvas in 1972. Her output up until then had been prodigious, some 2,000 works of art.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Series1, No.8

Sight failing rapidly, O’Keeffe employed a young assistant, Juan Hamilton, mainly to help her around the house but as a sculptor/potter himself, Hamilton encouraged her to paint again and take up pottery.

O’Keeffe was by now a well known figure, appearing on the cover of Life magazine in 1970 and also on television. She was awarded the Medal of Freedom from President Gerald Ford in 1977 and the National Medal of Arts in 1985 from President Ronald Regan.

The Georgia O’Keeffe museum opened in 1997 in Abiquiu New Mexico and is the first museum dedicated to a single female artist. (As the USA claims Georgia O’Keeffe as its own, so does New Mexico…)

Hamilton stayed with O’Keeffe until her death, aged 98 in 1986. O’Keeffe left most of her estate to him to the consternation of her relatives. Unsuccessful lawsuits ensued.

This retrospective at the Centre Pompidou, following the one in Madrid, is only one of three in this traveling exhibition, the last one being shown in Basel from January 23rd, 2022.

After O’Keeffe’s death in Santa Fe, her ashes were scattered as she had requested, from the top of the Pedernal Mesa, her beloved mountain, and the eternal view from her house at Ghost Ranch.

Practical information

Georgia O’Keeffe at the Centre Pompidou

September 8th-6th December 6th, 2021

Gallery 1, Level 6.

11am – 9 pm. Closed Tuesdays.

Reservations online.

Full-price admission is 14 euros

Youth (18-25) 11 euros.

Lead photo credit : Outside The Center Pompidou Paris © Pixabay

More in abstract art, Americans in paris, art show, centre pompidou, female artist

REPLY