MoMA Comes to the Fondation Louis Vuitton

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Fondation Louis Vuitton

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York and the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris have launched an exhibition – Being Modern: MoMA in Paris (Etre modern: le MoMA à Paris) – at the Fondation’s magnificent building in the Bois de Boulogne. Running through March 5, 2018, it is the first major exhibition of MoMA’s collections in France and showcases 200 of the 200,000 paintings, sculptures, drawings, prints, photographs, media and performance art works, architectural models and drawings, design objects, and film in MoMA’s collection.

As Quentin Bajac, formerly of the Pompidou Center in Paris and MoMA’s curator of the exhibition explains, “With Etre moderne, we hope to provide a history of modern art through the lens of MoMA’s ever-evolving collection.” And that it does.

The exhibition, which occupies all four floors of the Fondation, is presented in chronological order and includes both well-known and lesser-known creations.

The first part of the exhibition showcases works from 1929, the year MoMA opened, to 1939, and includes paintings by Paul Cézanne and Edward Hopper; photographs by Walker Evans; Constantin Brancusi’s iconic sculpture Bird in Flight; and a movie by Walt Disney. MoMA’s founding director, Alfred Barr, considered Cézanne “the father of modern painting,” and presented here is the artist’s The Bather (Le Baigneur). This painting was exhibited in MoMA’s inaugural exhibition, in 1929, along with nearly thirty of his other works. In The Bather, Cézanne breaks certain artistic conventions of the time, which explains Barr’s views on the artist.

The Bather by Paul Cezanne, 1885 / photo by Diane Stamm

Edward Hopper’s House by the Railroad (1925), painted when Hopper was just coming into prominence, was the first major painting to enter MoMA’s collection.

House by the Railroad by Edward Hopper, 1925 / photo by Diane Stamm

In keeping with its multidisciplinary focus, also included is footage of the Lime Kiln Club, filmed in The Bronx, New York, in 1913, and the earliest surviving feature-length film with an all-black cast. And Mickey Mouse fans will be delighted by Steamboat Willie, an eight-minute black-and-white film created in 1928 by Walt Disney and Ub Iwerks, the first sound cartoon in history and the first public appearance of Mickey. That MoMA had the foresight to recognize the cultural value of this short movie attests to the superb antennae of its founding stewards. It entered MoMA’s holdings in 1936.

Scene from Steamboat Willie by Walt Disney and Ub Iwerks, 1928 / photo by Diane Stamm

The exhibition proceeds through the works of the Cubists, Futurists, Dadaists, Surrealists, and abstract artists. Of particular interest is a triptych – The Castle, The Staircase, and The Return – by German artist Max Beckmann. Painted during the rise of the Nazis, several of his works were displayed in the notorious Degenerate Art exhibition in Munich in 1937, which was designed to inflame public opinion against modernism. Hitler gave a speech on the subject, and the next day Beckmann emigrated to the Netherlands. In 1942, MoMA mounted the exhibition Free German Art to highlight works that the Nazis had deemed “degenerate.”

Departure by Max Berkmann, 1932 / photo by Diane Stamm

Also included is Ernest Ludwig Kirchner’s Street, Berlin (Strassenszene Berlin). Painted in 1913, it focuses on two prostitutes. Using arbitrary colors and distorted forms, it presaged German Expressionism. It, too, was branded degenerate art and was sold to MoMA by the German government in 1939 after being removed from a state-owned German museum.

Street, Berlin (Strassenszene Berlin) by Ernest Ludwig Kirchner / photo by Diane Stamm

Salvador Dalí’s The Persistence of Memory and René Magritte’s The False Mirror are included as representatives of the Surrealists. Also on exhibition is Kazimir Malevich’s Suprematist painting, White on White. Removed from its stretchers, it was smuggled out of Nazi Germany wrapped around an umbrella.

Abstract Expressionism emerged in the postwar, Cold War world. As artists, especially American artists, unshackled themselves from European influence, there emerged such artists as Jackson Pollock, whose The She-Wolf (1943), the first painting by Pollock to enter a museum, and Echo Number 25, 1951, the quintessence of what critics Harold Rosenberg and Clement Greenberg called “action painting,” are included in the exhibition.

The She-Wolf, 1943, by Jackson Pollock / photo by Diane Stamm

Mark Rothko’s Color Field Painting No. 10, 1950, is also on display. It is a study in tone, value, harmony, and texture, and it seems so familiar today that it is difficult to fathom that, when MoMA acquired it in 1952, the work appeared so radical that one of the trustees resigned in protest.

No. 10, 1950, by Mark Rothko / photo by Diane Stamm

Things lighten up considerably with the evolution of art into Minimalism and Pop art, as represented by Ellsworth Kelly’s Colors for a Large Wall (1951), Jasper John’s Map (1961), and Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans (1962).

Kelly lived in Paris from 1948 to 1954 and was influenced by Matisse, Bonnard, and Arp. Colors for a Large Wall explores line, form, and color, and was gifted to MoMA by Kelly himself.

Colors for a Large Wall, 1951, by Ellsworth Kelly / photo by Diane Stamm

Jasper Johns’s Map, derived from the color maps of North America that children might use in elementary school, is a combination of chaotic brushstrokes and the grid of state lines. The primary colors are celebratory and even explosive and the overall effect uplifting. Johns would agree to sell the painting only to buyers who would donate it to MoMA, which is in fact what happened.

Map, 1961, by Jasper Johns / photo by Diane Stamm

And then we come to Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans, one of the works being exhibited for the first time in Paris. To quote Warhol, “If you want to know all about Andy Warhol, just look at the surface of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There’s nothing behind it.” We should believe him. But what he created was, nonetheless, art, and a product of the zeitgeist in which he lived, and epitomizes popular culture.

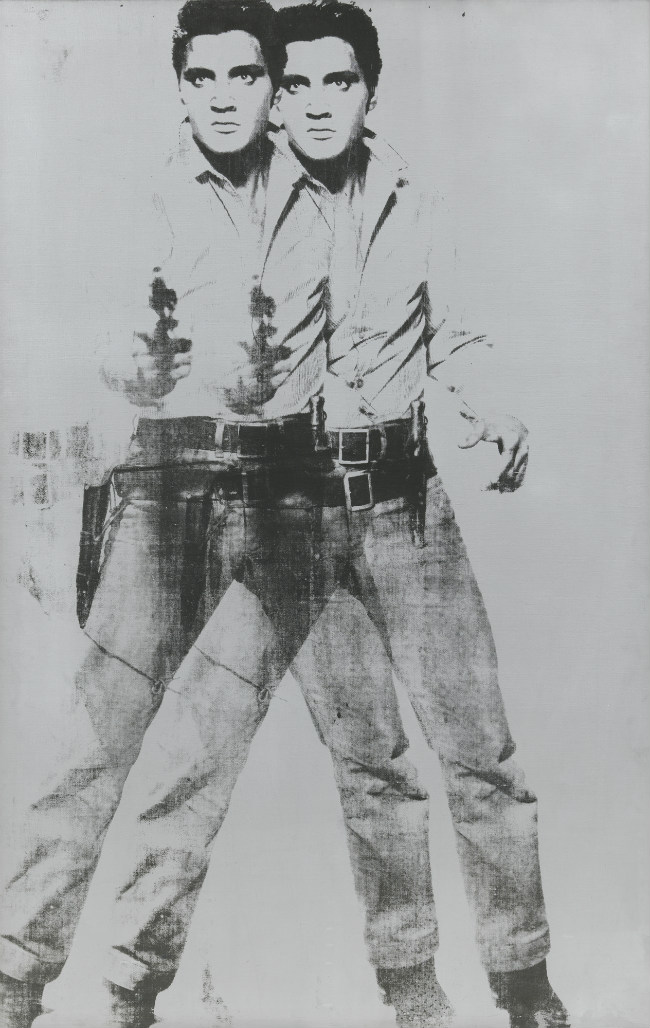

The exhibition also includes Warhol’s Double Elvis (1963), which was given to singer Bob Dylan in exchange for a modeling session at The Factory, Warhol’s New York City studio. Dylan then traded it to his manager shortly afterward for a couch.

Double Elvis, 1963, by Andy Warhol / Courtesy of the Fondation Louis Vuitton

Besides the paintings and films mentioned, the exhibition includes architectural renderings of Mies van der Rohe, drawings by architect Rem Koolhaas, digital imagery, performances, and 21st century works. The latter include the original set of emojis, which MoMA acquired in 2016. The word emoji is a Japanese neologism – a contraction of “image” (“e”) and “letter” (“moji”). They are offered as an example of the way we now exchange information. The original set of emoji comprised 176 symbols made available to subscribers of a Japanese mobile operator. Their creator, Shigetaka Kurita, derived them from mangas (Japanese comics), typographic symbols, and emoticons. Today there are more than 1,800 emoji, and, as everyone knows, they are ubiquitous.

Emoji, 1998–99, by Shigetaka Kurita / Courtesy of the Fondation Louis Vuitton

The exhibition includes installations that trace the origin and development of MoMA within a greater historical context. The names of three great ladies – philanthropists Lillie Bliss, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, and Mary Quinn Sullivan – cannot be mentioned often or loudly enough as the moving force behind the museum. They are a reminder of the great good that can come from those with time, money, intelligence, taste, and generosity.

The exhibition is extensive and worth the time it takes to explore in detail, including the information about MoMA’s history. The Fondation has a restaurant, Le Frank, named after Frank Gehry, the building’s architect, where you can relax over coffee, tea, or something more substantial if you need a break.

Your entry ticket also allows you to enter the Jardin d’Acclimatation, a 47-acre children’s amusement park, also in the Bois de Boulogne (just exit out the “back” door and you are in the Jardin). Opened in 1860 by Napoléon III and Empress Eugénie, it is a wonderful place to bring kids, and worth a walk-through on your way back to the metro. Note that the Jardin is currently undergoing a large-scale renovation project.

Fondation Louis Vuitton

8 Avenue de Mahatma Gandhi, Bois de Boulogne, Paris 16th. Tel: +33 (0)1 40 69 96 00 (+ 33 1 40 69 96 00)

Website: http://www.fondationlouisvuitton (click upper right corner for English)

Métro: Line 1, Les Sablons; take the exit Louis Vuitton Fondation. The Fondation is a 10- to 15-minute walk from the metro.

Open: Mon, Wed, and Thurs 11am to 7pm; Fri 11:00a to 9pm; Sat and Sun 9am to 9pm

Closed Tuesdays. Entrance fee: Full price 9 euro; reduced price 4 euro; the admission ticket includes access to the Jardin d’Acclimatation.

See http://www.fondationlouisvuitton.fr/Informations-pratiques.html for further ticketing information and on shuttle service available (2 euro per person), as well as events related to this and other exhibitions

Lead photo credit : Map, 1961, by Jasper Johns / photo by Diane Stamm