The Smart Side of Paris: The Meaning of Métier

As far as tourist attractions in Paris go, the museum of Arts and Métiers doesn’t rank very high. With a week to explore Paris, one rarely has the energy to move beyond the Louvre, the Orsay, and perhaps one other, such as the Orangerie. Even with the trendy République neighborhood just five blocks away, tourists don’t often venture down to the area around the museum. This might be a mistake because not only is the museum itself a spectacle of inventions and intellectual history, but the area surrounding it is quite pretty.

If you happen to take the metro to the museum, the first sight worth seeing is the metro station itself. Dressed in gold metal with huge bolts holding everything in place, the station gives the impression of being inside a finely polished submarine. The ceiling is adorned with giant gears and wheels, reflecting themes from the museum above it.

As you exit the metro, you are confronted with the lovely Café des Arts et Métiers.

Metro station Arts et Métiers. ©John Eigenauer

Café des Arts et Métiers. ©John Eigenauer

What does a museum of “Arts and Métiers” hold? A quick translation tells us that this is a museum of Arts and Crafts, making it sound like a Sunday craft fair in a park in the US. That is very far from being the case. The difference lies in the difficulty of translating the word “métier” and in the cultural differences between France and the United States surrounding this word. “Métier” might be translated as “craft,” “profession,” “trade,” or even “job.” But none of those translations quite captures the cultural depth of the word for the French.

To see how difficult it is to grasp this difference, the author of the book The Writing Life grapples with the French phrase, “C’est le métier qui rentre.” She writes, “In working-class France, when an apprentice got hurt, or when he got tired, the experienced workers said, ‘It is the trade entering his body.’” This is a noble attempt to translate the French phrase, “C’est le métier qui rentre.” The original French phrase lacks the words “his body.” The verb “rentrer” means “to return” and often carries a connotation of the destination being one’s home. The idea is that if inexperienced workers — workers who haven’t completely integrated their métier—made a mistake or perhaps got injured because of a mistake on the job, the métier had not fully taken hold of them. The time would come when they would truly master their métier, and such accidents and mistakes would not happen.

Exiting the metro at Arts et Métiers. © Connie Ma/Wikimedia Commons

One might have translated this passage, “It is the craft coming home,” or, less literal and perhaps less precise, “The craft is teaching him.” The term “his body,” was a good choice to convey a phrase that is difficult to translate to an English-speaking audience; she might have chosen “mind” or “life” equally well. But perhaps the best translation of métier is “calling.”

English has, to some degree, tried to compensate for this cultural distinction by adopting the French word itself. In fact, the 2023 Merriam Webster dictionary wrestles with the meanings of various synonyms in English, such as “employment,” “job” and “occupation.” But, the authors caution, “Métier, a French borrowing acquired by English speakers in the 18th century, typically implies a calling for which one feels especially fitted.” Indeed, one hears French people speak frequently of their métier; I have seen metro advertisements featuring testimonies from individuals expressing their gratitude for certain social projects helping them to find their métier.

And so, as we enter the museum of Arts and Métiers, we do so knowing and understanding that it is dedicated to the products created by people devoted to their various callings — callings that helped define themselves as people and in which they took great pride.

Lavoisier’s laboratory at the Musée des Arts et Métiers. ©John Eigenauer

The museum’s first exhibit is Antoine Lavoisier’s laboratory. To a large degree forgotten today, one of his biographers lists Lavoisier as, “along with Copernicus, Galileo, Newton, and Einstein, one of the greatest and most important scientists ever.” That is some elite company. As the founder of modern chemistry, Lavoisier earned his place there.

Lavoisier’s dedication to scientific discovery is legendary. He once tried “ingesting nothing but milk” to see how it might affect is health; he supposedly tried living in a completely dark room to learn how the human eye responded to slight difference in lighting; and he kept a flask of water just below boiling for more than 100 days to see if it might be distilled into some solid form. He was the first person to truly understand combustion, the first to propose the Law of the Conservation of Mass, the first to discover that water was composed of oxygen and hydrogen, and he played a key role in the formation of the metric system. He was devoted to political reform and to extending human rights for all; sadly, he was guillotined during The Terror.

Leaving Lavoisier’s lab, the museum is divided into exhibits on scientific instruments, materials (such as paper), construction (including architecture), communication technologies, energy technologies, mechanics, and transportation. As you walk through the museum, you are reminded how intimately connected technology and craftsmanship were, as is the case with the beautiful 18th century clocks on display, each part crafted by hand.

Clocks on display at the Musée des Arts et Métiers. ©John Eigenauer

Today, many of our technologies are opaque — how they work is obscured because so many of their functions depend on microprocessors (hidden) and software (hidden). The museum tries to lay bare the craftsmanship behind technologies such clocks, microscopes, and barometers that were foundational to the intellectual and scientific advancement of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. As I walk through the museum, I am reminded of scientific progress that went hand in hand with the craftsmanship at the heart of French technologies on display.

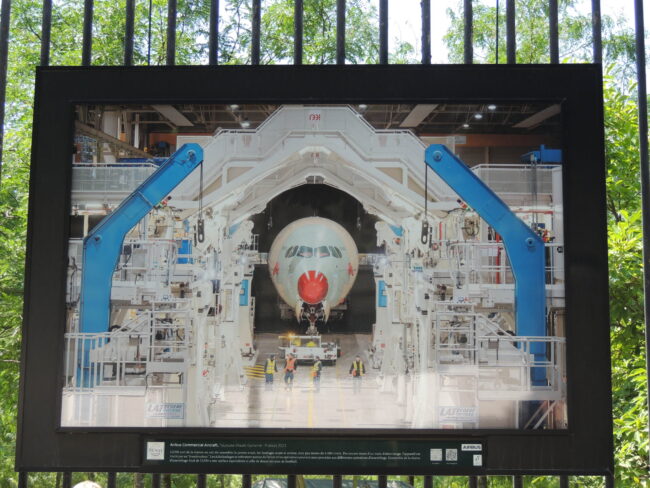

Continuing the long tradition of French dedication to métiers, from March 18th until July 16th of this year (2023), the gates around the Jardin de Luxembourg were decorated with an exhibition of 80 large photographs. The title of the exhibition was “The Beauty Hidden in Industry.” In descriptions of the photo exhibit, the word métier appeared multiple times. There were pictures of giant jet engines, human prosthetics, and pasta manufacturing; there was shipbuilding, shoe making, and bottle manufacturing. The images were stunning; equally striking was how frequently people appear in the images, practicing their métier in crafting car bodies, tiny watch parts, and of course, food.

Watches at the exhibit “The Beauty Hidden in Industry”. ©John Eigenauer

I sense that it is common for French people to see their “work” as their “craft,” that is, what they do for a living often coincides with a deep sense of pride in and dedication toward what they do and is deeply connected to who they are. For many French people, one’s “métier” involves their sense of self. The museum of Arts et Métiers, I think, is not merely a demonstration of the advance of technology from microscopes to microprocessors, but a celebration of the human devotion to one’s craft that is seen as part of being French.

Enjoy more articles in the “Smart Side of Paris” series here

DETAILS

Musée des Arts et Métiers

60 Rue Réaumur, 3rd arrondissement

Tel: +33 (0)1 53 01 82 00

Closed Mondays. Open Tuesday-Sunday from 10 am to 6 pm. Late closure on Friday evenings at 9 pm.

The full-price ticket to the permanent collection is 9 euros.

Recycling depicted at the exhibit “The Beauty Hidden in Industry”. ©John Eigenauer

An airplane depicted at the exhibit “The Beauty Hidden in Industry”. ©John Eigenauer

Lead photo credit : Printing press at the Musée des Arts et Métiers. ©John Eigenauer

More in Antoine Lavoisier, Café des Arts et Métiers, Musée des Arts et Métiers, Museum, The smart side of Paris