On the Road with Jack Kerouac at the Musée des lettres et manuscrits

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

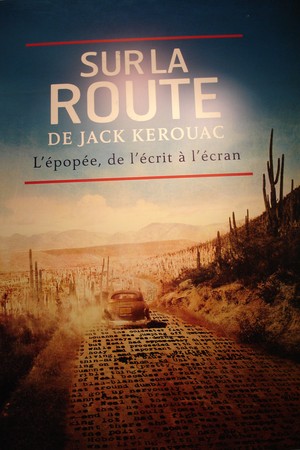

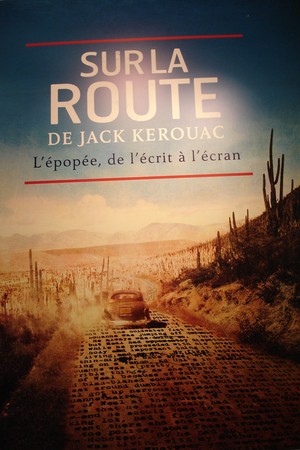

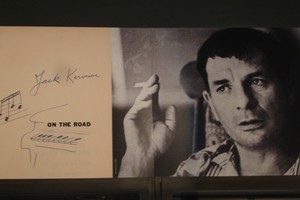

Leave it to the French to mount a pitch-perfect paean to that most quintessential of American symbols: the open road. The Musée des lettres et manuscrits (Museum of Letters and Manuscripts), in collaboration with the French film company, MK2 Productions, has done just that in its exhibition, “Sur la Route de Jack Kerouac: L’épopée, de l’écrit à l’écran” (“On the Road: The Epic, from Writing to the Screen”), at the museum until August 19.

Leave it to the French to mount a pitch-perfect paean to that most quintessential of American symbols: the open road. The Musée des lettres et manuscrits (Museum of Letters and Manuscripts), in collaboration with the French film company, MK2 Productions, has done just that in its exhibition, “Sur la Route de Jack Kerouac: L’épopée, de l’écrit à l’écran” (“On the Road: The Epic, from Writing to the Screen”), at the museum until August 19.

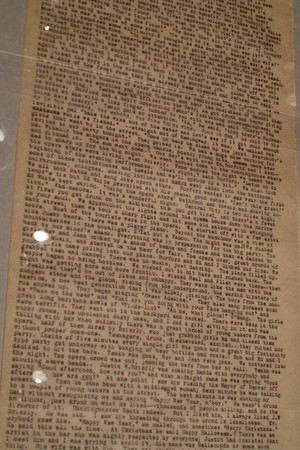

Kerouac had a story he wanted to tell, and he searched for years for a way to tell it. He wanted to write fast – “because the road is fast,” he explained. Having to change the paper in his typewriter broke his writing momentum and hampered the “spontaneous prose” style he sought. He considered typing on a roll of shelf paper, but in the end he glued together sheets of tracing paper, which he trimmed to fit his typewriter wheel. The final product was the 120-foot-long scroll of 370 pages and 125,000 words, with no paragraphs or page breaks, which is the centerpiece of the exhibition.

Fueled by coffee, not the Benzedrine of the myth, Kerouac wrote his magnum opus between April 2 and April 22, 1951. He was 29 years old. He averaged 6,000 words a day, including 12,000 on the first day and 15,000 on the last. “I rolled it out on the floor and it looks like a road,” he wrote.

Jack Kerouac was born Jean Louis Lebris Kerouac on March 12, 1922, in the working-class town of Lowell, Massachusetts. His parents were Quebec immigrants with Breton roots. Kerouac’s first language was joual, a dialect of Quebecois French, and he didn’t become fluent in English until he was six years old.

Kerouac lived a peripatetic life even before meeting Neal Cassady, who became a pivotal influence in his life. He attended Columbia University, joined the Merchant Marines, and was drafted to fight in World War II but was declared unfit for service on the grounds of “schizophrenia.” Eventually, he adopted a bohemian lifestyle and met writer William Burroughs and poet Allen Ginsberg. In 1946, he met Cassady, who had just been released from prison and was seeking unrestrained freedom.

Kerouac was fascinated by Cassady and become an unapologetic acolyte, willing to follow his leader anywhere. That he happened to have the desire to write was integral to his friendship with Cassady. Kerouac’s life was working class and dull. He was seeking experiences to write about, and Cassady and the road were his ticket.

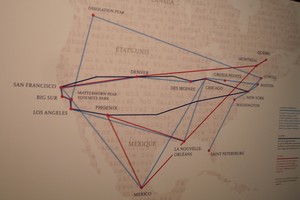

Life on the road, as depicted in the original scroll, was raw and tough and full of sex, drugs, alcohol, and trips crisscrossing the United States and Mexico. The loneliness and searching are evident. Kerouac kept detailed notes on the trips, and it is from these notes that the scroll was created.

Life on the road, as depicted in the original scroll, was raw and tough and full of sex, drugs, alcohol, and trips crisscrossing the United States and Mexico. The loneliness and searching are evident. Kerouac kept detailed notes on the trips, and it is from these notes that the scroll was created.

Although Kerouac wrote the scroll in less than three weeks, the book wasn’t published until 1957. It was rejected by multiple publishers as being too raw or too controversial for post-World War II America. It was sui generis, and few people were willing to take a chance on what would come to be recognized as a groundbreaking work.

Finally, in 1955, Viking Press editor Malcolm Cowley agreed to publish the book if Kerouac made certain changes. Tired of rejections, Kerouac did what Cowley asked. He reworked and shortened the text, made changes in the vocabulary, and watered down explicit sexual content. The revised manuscript was finally published in 1957 by Viking Press and three years later in France by Gallimard.

It is this shorter version of the scroll that most readers are familiar with. Unlike the text published in 1957, the scroll uses the characters’ real names, which had been changed to prevent libel suits. Sal Paradise is Jack Kerouac, Dean Moriarty is Neal Cassady, and Carlo Marx is Allen Ginsberg. Of the published text, Ginsberg said, “The published novel has nothing to do with the uninhibited book that Kerouac typed in 1951. One day when everyone is dead, the original will be published in all its glory.”

As Ginsberg prophesied, the original scroll was in fact published – in 2007 by Viking on the 50th anniversary of its initial publication. Three years later, Gallimard published the French version, under the title Sur la route – le rouleau original (On the road – the original scroll).

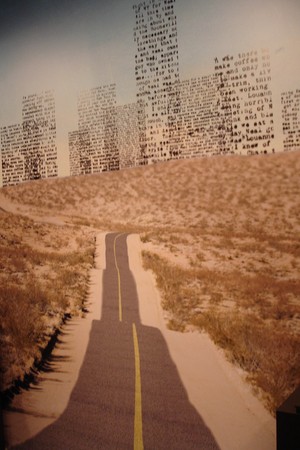

As for the scroll itself, it is displayed in a specially constructed case more than 29 feet in length, and the road leitmotif is artfully continued up one wall of the exhibition space.

As for the scroll itself, it is displayed in a specially constructed case more than 29 feet in length, and the road leitmotif is artfully continued up one wall of the exhibition space.

In May 2001, the scroll came up for auction at Christie’s in New York, where it was bought by Jim Irsay, owner of the Indianapolis Colts football team and a rock music aficionado, for $2.5 million. It is being displayed for the first time in Paris in the exhibition.

The final section of the exhibition is devoted to the making of the movie, “On the Road,” which was released at the Cannes Film Festival in May.

American film director, producer, and screenwriter Francis Ford Coppola acquired the rights to the book in 1968. Coppola finally found the director he was looking for in Brazilian director Walter Salles. Exhibition cosponsor MK2 Productions produced the film.

The exhibition includes Salles’s annotated screenplay, sketches for the sets, photographs of the filming, and a who’s who of actors and the characters they play. Included is a letter Kerouac wrote to actor Marlon Brando offering him the chance to buy the rights, to which Brando never replied.

On the Road became a worldwide best seller, and the exhibit includes a scrim of book covers from editions published in many languages around the world. It also became the manifesto of the beat generation. The exhibition shows Kerouac to be more serious and more substantive than one might have assumed; he was well read and was influenced by the work of both American and French authors, including Jack London, Mark Twain, Thomas Wolfe, Walt Whitman, Rimbaud, Céline, Balzac, and Proust. Through a quirky confluence of factors – Kerouac’s father had recently died, he was searching for something, he met Cassady, and he wanted to write – Kerouac managed to both create and capture a certain zeitgeist.

On the Road became a worldwide best seller, and the exhibit includes a scrim of book covers from editions published in many languages around the world. It also became the manifesto of the beat generation. The exhibition shows Kerouac to be more serious and more substantive than one might have assumed; he was well read and was influenced by the work of both American and French authors, including Jack London, Mark Twain, Thomas Wolfe, Walt Whitman, Rimbaud, Céline, Balzac, and Proust. Through a quirky confluence of factors – Kerouac’s father had recently died, he was searching for something, he met Cassady, and he wanted to write – Kerouac managed to both create and capture a certain zeitgeist.

After its publication, Kerouac was in demand and in the news. But he could not understand the superficiality of the media, and he withdrew. He continued to write, but he died on October 21, 1969, at age 47, from an internal hemorrhage, a result of a lifetime of heavy drinking.

This exhibition, which also celebrates the 90th year of Kerouac’s birth, captures the essence of Kerouac and all he stood for. It traces the trajectory of his life and of a movement that is long over. But the symbol of the road remains.

This exhibition, which also celebrates the 90th year of Kerouac’s birth, captures the essence of Kerouac and all he stood for. It traces the trajectory of his life and of a movement that is long over. But the symbol of the road remains.

Musée des lettres et manuscrits

Tel: 01 42 22 48 48

222 Bd Saint-Germain, Paris 7th

Metro: Rue du Bac – Line 12

RER C: Musée d’Orsay

Bus: 63, 68, 69

Open: Tues–Sun 10am–7pm

Thurs open until 9:30pm

Handicapped-accessible

Entrance fee: 7 euros

Reduced fee: 5 euros

Group fee (10 or more): 4 euros

Free for children 12 and under and for handicapped

Email

Subscribe for FREE weekly newsletters.

BonjourParis has been a leading France travel and French lifestyle site since 1995.

Readers’ Favorites: Top 100 Books, imports & more at our Amazon store

We update our daily selections, including the newest available with an Amazon.com pre-release discount of 30% or more. Find them by starting here at the back of the Travel section, then work backwards page by page in sections that interest you.

Current favorites, including bestselling Roger&Gallet unisex fragrance Extra Vieielle Jean-Marie Farina….please click on an image for details.

Click on this banner to link to Amazon.com & your purchases support our site….merci!

More in France artists, French artists, Musée des lettres, Paris art exhibits, Paris art museums, Paris writers, writers in Paris