‘A Giddy, Ridiculous Tower’: Historic Controversy over the Eiffel Tower

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

“Imagine for a moment a giddy, ridiculous Tower dominating Paris like a gigantic black smokestack, crushing under its barbaric bulk Notre Dame, the Tour Saint-Jacques, the Louvre, the Dome of Les Invalides, the Arc de Triomphe, all of our humiliated monuments will disappear in this ghastly dream.” – Artists against the Eiffel Tower, Le Temps 1887

The Eiffel Tower, one of the most iconic structures in the world, was not always embraced with open arms. In fact, its construction was met with significant controversy and criticism. Notable critics in France attacked the Eiffel Tower as it was being built, with some going as far as to predict that it would be the ruination of Paris.

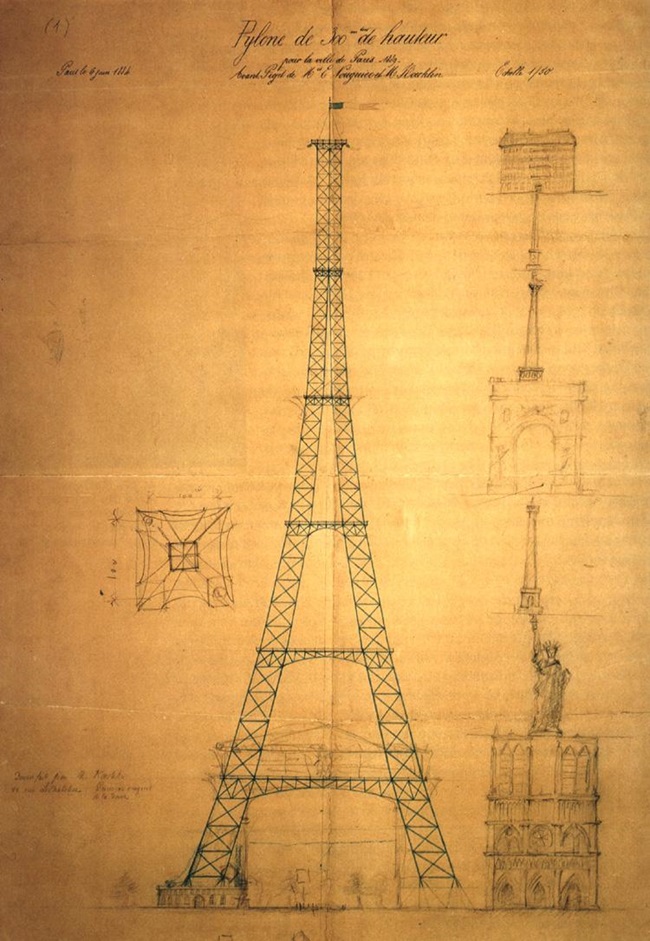

The 10th World Exhibition, held in 1889, marked the 100th anniversary of the French Revolution and to celebrate, a competition was launched to “study the possibility of erecting an iron tower with a square base on Champ de Mars, 410 feet wide and 984 feet high.” Of the 107 projects proposed, Gustave Eiffel’s concept won. The primary purpose of the tower’s construction was to serve as the entrance arch to the exhibition and showcase France’s industrial and technological achievements to the world.

Blueprint of the Eiffel Tower by one of its main engineers, Maurice Koechlin (ca. 1884). Authorization given by Koechlin Family. Photo: Maurice Koechlin, Émile Nouguier/Wikimedia Commons

“A truly tragic streetlamp” – Leon Bloy

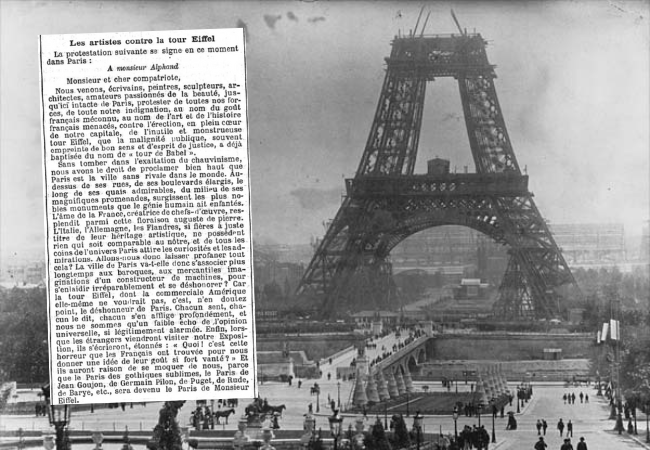

Artists, architects, and literary figures protested the tower, denouncing it as a useless and monstrous construction that threatened French art and history. Despite its initial intention as a temporary structure, critics were indignant in their objections and went as far as to sign a petition titled “Artists against the Eiffel Tower,” which was published in the newspaper Le Temps on February 14, 1887.

The open letter was addressed to Adolphe Alphand, curator of the 1889 World Exhibition, and explained the opposition’s belief that the Eiffel Tower would be an eyesore detracting from the beauty of Paris.

An extract from the open letter:

“We, writers, painters, sculptors, architects and passionate devotees of the hitherto untouched beauty of Paris, protest with all our strength, with all our indignation, in the name of slighted French taste, in the name of art and of French history threatened, against the erection, in the heart of our capital, of the useless and monstrous Eiffel Tower, which public malignity, often marked by common sense and the spirit of justice, has already named ‘Tower of Babel’. Without falling into the exaltation of chauvinism, we have the right to proclaim that Paris is the unrivaled city of the world. Above the streets, the widened boulevards, and the magnificent walks rise the most noble monuments that the human race has produced. The soul of France, creator of masterpieces, shines amidst this august flowering of stones. Italy, Germany and Flanders, so justifiably proud of their artistic legacy, possess nothing comparable to ours, and from all corners of the globe Paris attracts curiosity and admiration. Are we going to let all this be profaned? Will the city of Paris go on to associate itself still further with the eccentric, mercantile imaginings of a machine builder, to become irreparably ugly and dishonor itself? For the Eiffel Tower, which the commercial-minded America itself would not want, is, doubtless, the dishonor of Paris. Everyone feels it, everyone says it, everyone is deeply aggrieved by it, and we are but a weak echo of the universal opinion, so legitimately alarmed. Finally, when the foreigners come to visit our Exhibition, they will exclaim, astonished: ‘What? It is this horror that the French have found to give us an idea of their taste, so much vaunted?’ And they will be right to make fun of us, because the Paris of the sublime Gothic, the Paris of Jean Goujon, Germain Pilon, Puget, Rude, Barye, etc., will have become the Paris of M. Eiffel. It suffices, moreover, to realize what we are doing, to imagine for a moment a vertiginously ridiculous Tower dominating Paris, as well as a gigantic factory chimney, crushing with its barbarian mass Notre-Dame, Sainte-Chapelle, the dome of the Invalides, Arc de Triomphe, all our monuments humiliated, all our architectures shrunken, which will disappear in this astonishing dream. And for twenty years, we will see, stretching out over the entire city, still quivering with the genius of so many centuries, we will see the odious shadow of the odious column of bolted sheet metal stretch like an ink stain. It’s up to you, those who love Paris so much, who have embellished it so much, who have so often protected it against the administrative devastation and the vandalism of industrial enterprises, that it is the honor to defend once more. We leave it to you to plead the cause of Paris, knowing that you will deploy all the energy, all the eloquence that must inspire, in an artist such as yourself, love for what is beautiful, what is great, what is right. And if our cry of alarm is not heard, if our reasons are not listened to, if Paris persists in the idea of dishonoring Paris, we will have at least, you and us, heard a protest that honors it.”

Among the long list of signatories are well-known figures such as renowned architect and constructor of the Opera Garnier, Charles Garnier, as well as Charles Gounod, William-Adolphe Bouguereau, François Coppée, Alexandre Dumas fils, Charles-Marie Leconte de Lisle and Sully Prudhomme.

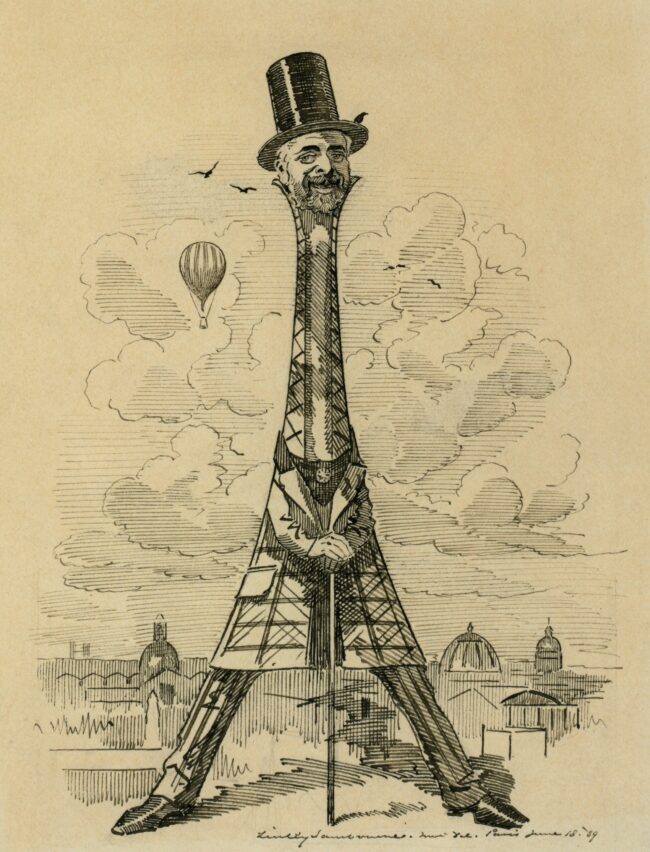

Caricature of Gustave Eiffel in the form of the Eiffel Tower by Edward Linley Sambourne. 1889. Public domain

Gustave Eiffel defended his project tooth and nail, responding to the criticisms by proclaiming the artistic and engineering merit of the tower. In his response, he also acknowledged concerns about its structural integrity, with some fearing that it might collapse due to its unprecedented height. He compared it to the Egyptian pyramids in an interview with the same newspaper, Le Temps.

“I will tell you all my thoughts and all my hopes. I believe, for my part, that the Tower will have its own beauty. Because we are engineers, do we believe that beauty does not concern us in our constructions and that at the same time that we make solid and durable, we do not strive to make elegant? Do not the true conditions of force always conform to the secret conditions of harmony? The first principle of architectural aesthetics is that the essential lines of a monument are determined by perfect appropriation to its destination. Now, what condition have I had, above all, to take into account in the Tower? Wind resistance. Well! I claim that the curves of the four edges of the monument, as calculated, starting from a large and unusual thickness at the base, tapering to the top, will give a great impression of strength and beauty; for they will translate to the eyes the boldness of the design as a whole, just as the many voids in the very elements of the construction will strongly assuage the constant concern not to deliver unnecessarily to the violence of hurricanes, surfaces dangerous for the stability of the building. There is, furthermore, in the colossal, an attraction, a particular charm, to which theories of ordinary art are hardly applicable. Would you say that it is through their artistic value that the Pyramids have so powerfully struck the imagination of men? After all, are they anything but artificial hills? And yet, where is the visitor who remains indifferent in their presence? Who has not come back from them filled with irresistible admiration? And what is the source of this admiration, if not the immenseness of the effort and the grandeur of the result? The Tower will be the tallest building that men have ever built. Will it not be so grandiose in its own way? And why would that which is admirable in Egypt become hideous and ridiculous in Paris?”

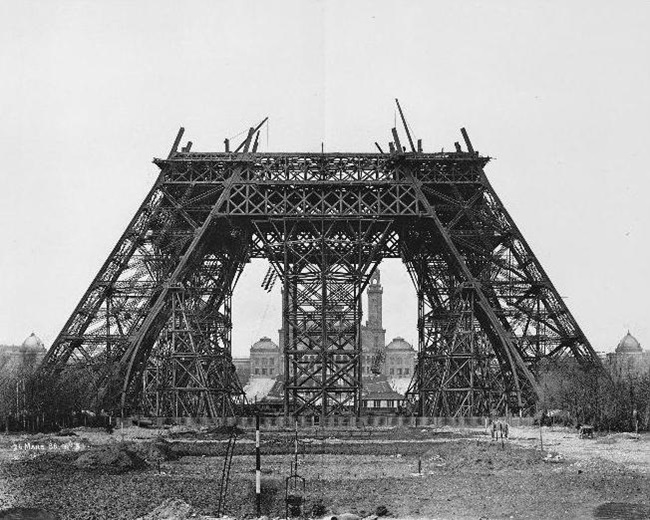

Eiffel Tower: Assembly of horizontal beams on the middle scaffolding. Wikimedia Commons

The birth of an icon

The controversy, however, died out in the presence of the completed masterpiece and its enormous popular success. The tower was inaugurated on March 31st, 1889, when Gustave Eiffel climbed its 1,710 steps to raise the tricolor French flag at the top. For 40 years, it was the highest building in the world, before the Chrysler Building overtook it in 1929.

During its design and construction, 50 engineers and designers created over 5,000 drawings and over 100 laborers prefabricated over 18,000 different pieces. On site at the Champ de Mars, between 150 and 300 laborers worked to assemble the giant construction. Today, nearly 800 people are involved in making the Eiffel Tower operational every day. From concessionaires to subtenants and service providers, the tower continues to offer direct employment while attracting tourists from across the world, contributing to both the local and national economy.

Eiffel Tower. Photo: William O’Such

Initially intended to be dismantled only 20 years after its completion, the Eiffel Tower was saved thanks to its proven scientific utility. When he first presented the project, Gustave Eiffel knew that only the tower’s scientific usefulness could preserve it from its adversaries and extend its lifespan: “It will be an observatory and laboratory for all, such as has never been made available to scientists. That is why, from the very first day, all our scholars have encouraged me with their best wishes.”

A meteorology laboratory was installed on the third floor and a small wind tunnel built at the foot of the tower. From August 1909 to December 1911, Eiffel performed 5,000 studies and tests at the Tower. On November 5, 1898, Eugène Ducretet transmitted the first radio contact from the Eiffel Tower to the Pantheon, covering 4 kilometers, which marked the beginning of utilizing the tower for radio transmissions, with subsequent transmissions extending to London. General Gustave-Auguste Ferrié, a pioneer in French radio technology, advocated for using the tower as an antenna for civilian broadcasts, leading to its role in public radio broadcasting from 1921 onwards. The tower became a crucial military building during World War I, facilitating communication with various regiments and even capturing German messages in 1918, thus hindering their advances.

A landmark dominating the Parisian skyline

In 1897, the Lumière brothers placed their camera in the lift and filmed the Palais du Trocadéro, the esplanade and gardens as it ascended through the monument’s metal structure. Since then, the tower has had a long love affair with cinema.

Over 300 million visitors have come to see the Eiffel Tower since it opened, with 75% from overseas, making it the most visited ticketed monument in the world. Known as an iconic landmark, the Eiffel Tower has become one of the most recognizable monuments globally. Initial concerns that the tower would dominate the Parisian skyline aren’t entirely unfounded, but it certainly hasn’t become the “dishonor of Paris” and has instead attracted “curiosity and admiration from all corners of the globe.”

The Olympic and Paralympic medals for the Paris 2024 Games will be unique as they will contain a piece of original iron from the Eiffel Tower. The medals are designed by Chaumet, a renowned jewelry house, and are inspired by the hexagon shape of France, with iron from the Eiffel Tower integrated into the center of each medal.

It’s not the first time that parts of the iconic Tower have been monetized or marketed. For Christmas in 2016, the Eiffel Tower sold 300 of its “Diamond Lights”, authentic bulbs from the tower as decorative collectibles. At a price of €450, purchasers could own a limited-edition, unique piece of history.

Oh the Iron-y

Despite the initial fierce opposition from influential individuals, the Eiffel Tower ultimately prevailed, becoming an enduring symbol of Paris. Its journey from a widely criticized structure to a beloved icon is a testament to its enduring power and appeal.

Claims from the “Artists against the Eiffel Tower” that “when the foreigners come to visit our Exhibition, they will exclaim, astonished: ‘What? It is this horror that the French have found to give us an idea of their taste… they will be right to make fun of us”, have been proven incorrect, as the tower has captured the hearts of people worldwide.

While their concerns were not entirely unfounded, history has shown that the Eiffel Tower has become an integral part of Paris’s identity, attracting millions of visitors and inspiring countless artists from around the world. Not all were convinced though, as it’s often claimed that famed writer Guy de Maupassant frequently ate at the restaurant in the tower, not because he admired the structure, but because it was the one place in Paris where he could not see it…

More in Eiffel Tower, Gustave Eiffel, Paris history