Eiffel: The Magician of Iron and the World’s Tallest Tower

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

2023 marks the centennial of the death of Gustave Eiffel. It is impossible to think of Paris without the tower named after him; for almost 130 years the Eiffel Tower has been the global symbol of the city. But Eiffel was far more than the builder of a one-off tower. An innovator in iron construction across the world, he experimented in aerodynamics and pioneered airplane design.

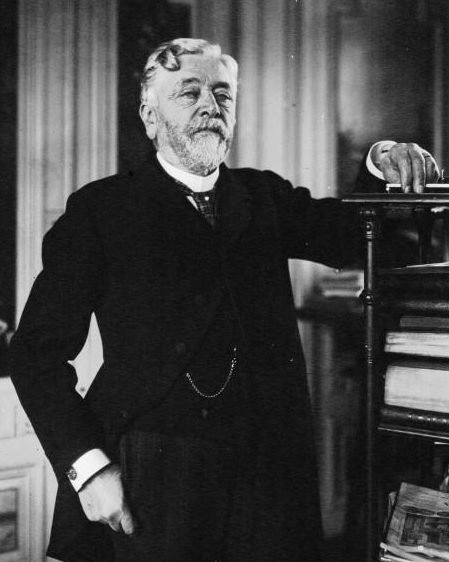

Eiffel in 1888, photographed by Félix Nadar. Wikimedia Commons

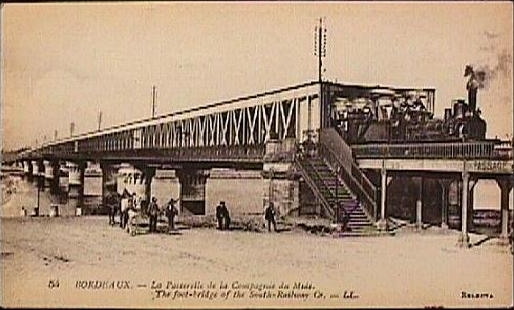

He was born in Dijon in 1832 and studied metallurgy before entering the employ of an engineer-builder called Nepveu. He quickly became Nepveu’s “right hand man” and at the age of 26 was more or less put in charge of building a new bridge over the River Garonne in Bordeaux. Measuring 500 meters, the iron girder bridge was one of the longest in France at the time. Its foundations stand on chambers of compressed air, a technique that Eiffel would specialize in.

The Bordeaux bridge, Eiffel’s first major work. Wikimedia Commons

The years that followed saw Eiffel start his own business and build up an impressive portfolio of engineering projects, including bridges and even prefabricated churches in South America, the railway station at Pest in Hungary, and the Nice Observatory. He specialized in bridges and viaducts for the rapidly expanding railway network and two of his most ambitious projects were the bridge over the River Douro at Oporto, Portugal, and in 1879 the bridge over the Truyère Gorge at Garabit in the Cantal. They were both arched iron bridges, the Oporto bridge being built without scaffolding. Instead, it extended outwards from the riverbanks and met in the middle. The bridge at Garabit soared over the valley at a height of 122 meters, yet apparently rested on light-as-air lacy pillars; it was a marvel of modern engineering. It was also a trial run for the Eiffel Tower, although Eiffel obviously didn’t know this at the time. The complex calculations needed to ensure each piece was perfectly placed and aligned, and the methods of construction, as well as the team of engineers and technicians, would be used again nearly a decade later.

The Budapest Nyugati railway station. Credit: Herbert Ortner / Wikimedia Commons

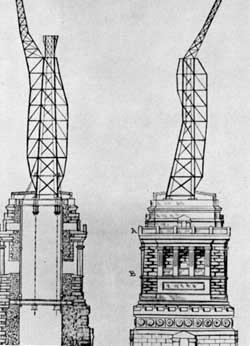

The other “dry run” was the building of the metallic support inside Bartholdi’s Statue of Liberty. This gift from France to the United States was going to be over 46 meters tall — how would it avoid collapsing under its own weight? Eiffel called on all his expertise acquired in Portugal and the Cantal and devised a column of four vertical girders held together with diagonal struts and trellis. The copper plates covering it — to minimize corrosion — were suspended so they did not bear their own weight.

Interior structural elements of the Statue of Liberty designed by Gustave Eiffel. Wikimedia Commons

By the 1880s, the “magician of iron” was in the top league of metallic engineers and in 1885, he won the competition to build a landmark tower for the 1889 Universal Exhibition. The tower is now such an integral part of the Paris skyline that it is hard to realize just how controversial it was at the time. At 300 meters it was by far the tallest structure ever built. It generated the same level of antipathy as the Tour Montparnasse would nearly a century later: a Petition des Artistes gathered the signatures of renowned writers, artists and sculptors including Guy de Maupassant, Alexandre Dumas fils, Charles Garnier and the composer Gounod. All deplored Eiffel’s design, claiming that it “dishonored” the city and replaced the “sublime Gothic” Paris with “M. Eiffel’s Paris,” ie. an ugly modern Paris. To be fair, several later softened their attitude: Garnier, who was a friend of Eiffel’s, wrote him to say that since the project was going ahead the important thing was to make it the best structure possible.

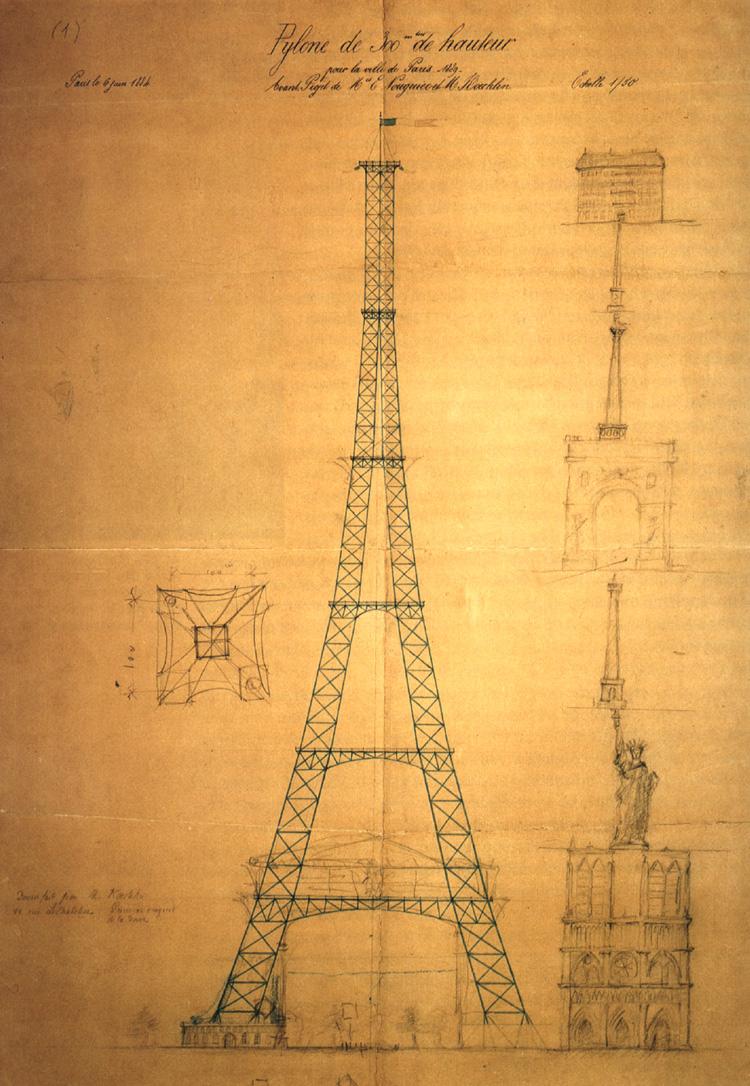

Koechlin’s first drawing for the Eiffel Tower. Note the sketched stack of buildings, with Notre-Dame at the bottom, indicating the scale of the proposed tower. Wikimedia Commons

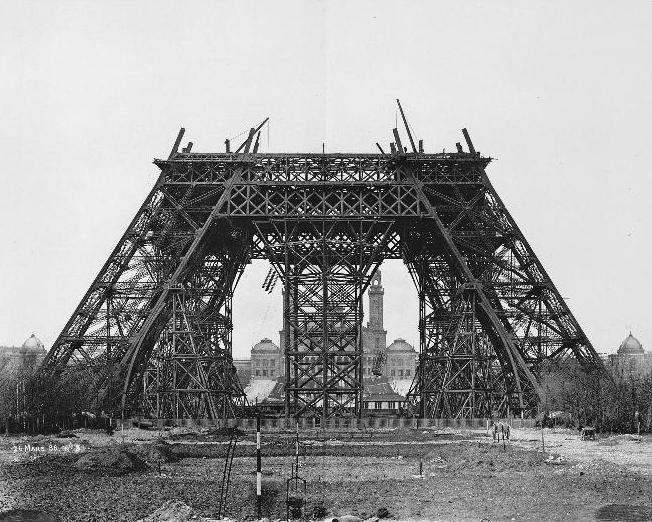

Despite his years of engineering experience, Eiffel had not attempted anything this ambitious before. He delegated much of the detail to his younger collaborator Maurice Koechlin who drew up more than 1,700 drawings and over 3,000 studies detailing more than 18,000 separate components. People had grave doubts about the tower; it seemed to defy the laws of physics. How could such a tall structure avoid collapsing or being blown apart by high winds? Was it leaning to the right… or to the left? Onlookers marveled at the workmen standing high in the air on wooden scaffolding (the tower might be built of iron but the scaffolding was still wood and rope, the same as had been used since the Middle Ages). Of course, there were no safety harnesses or helmets. Despite that, out of 250 workers there were only three accidents and only one death — and that occurred after the tower had been completed.

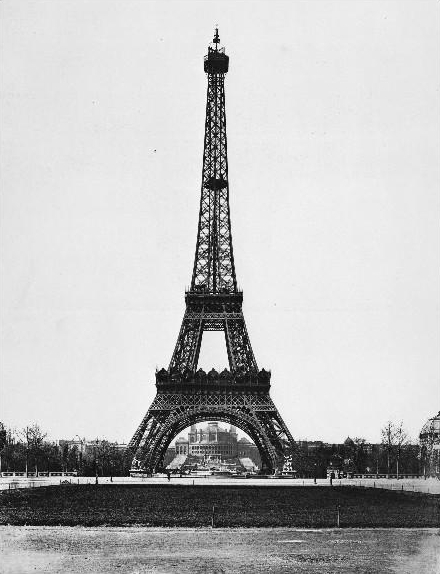

The Eiffel Tower in March 1888

Eiffel had just two years, 1887-1889, to build it and managed it to the exact day he had predicted in 1885, a record time in construction history. When the World Exhibition opened, the tower was an immediate success: in six months it welcomed almost 2 million visitors (including Thomas Edison who offered Eiffel his new phonograph in return). Ticket sales almost repaid the construction costs. People were especially delighted with its never-seen-before electric illumination. However, that didn’t stop them from calling for its demolition when the next Universal Exhibition was planned (1900). But by then Marconi’s wireless was the latest gadget and the mounting of a radio antenna at the top of the Eiffel Tower secured its future.

The Eiffel Tower in March 1889

Sadly, Eiffel’s reputation was severely damaged when he let himself get involved with the Panama Canal project. He had agreed to build six locks but the financing of the canal was based on a swindle. By 1892, the Panama Canal Company had collapsed amid a huge financial scandal, sweeping up Eiffel. He was put him on trial and despite the lack of real evidence of guilt, sentenced to two years in prison. Fortunately the sentence was overturned before it started.

By now aged 60, Eiffel decided that this would mark the end of his metallic engineering career. But he was never a man to seriously consider retirement and instead he turned his attention to meteorology, measuring wind speeds based on his earlier work on making tower safety. By the early 20th century, he was experimenting with aerodynamics and built a wind tunnel on the Champs de Mars. Here he conducted experiments to improve the efficiency of airplane wings and propellors for the fledgling French Air Force. In 1912 he moved to a purpose-built laboratory in Auteuil. He was extremely generous, taking out patents for his innovations but not enforcing them so that his designs were freely available; all he asked was a “name check.”

Eiffel in 1910. Credit: Agence de presse Meurisse – Bibliothèque nationale de France/ Wikimedia Commons

When the First World War broke out, Eiffel put the lab at the disposal of the Ministry of War and the Navy and tested wings on mono-, bi- and even tri-planes in an attempt to create a fast fighter plane that could compete with Germany. After the war he handed the laboratory over to the government aeronautical service. It is still in use today.

If there was one word which could describe Eiffel, it would be “driven.” He had a powerful personality, which shows in the portrait photographs that survive. He also aged from a good looking young man to “distinguished” in old age. He studied for his degree at night school and never stopped working. No letters or photographs exist that even hint at a life outside work and his family. He considered three women as potential wives, checking off their credentials as if he was interviewing them for a job. He eventually married the fourth woman but she has left barely a mark on history. Eiffel disliked her name, Marie, and insisted on calling her Marguerite. That seems to sum up his attitude to marriage and his wife: a good housewife and bearer of children (she bore seven and died at the age of 32). Even after her death, he scarcely mentioned the event to the rest of his family, as if she had been of no importance.

On the other hand, he poured all his affection on his daughter Claire. As she grew up, she took an increasing role in his business affairs and arguably took the place of her mother as Mme Eiffel (despite being married herself). He did not share his love with his other children: at his death Claire inherited the bulk of his estate while her siblings received much smaller inheritances and one daughter, Laure, nothing at all.

Gustave Eiffel passed away on December 27th, 1923, at the age of 91. A generous but not entirely likeable man, he pushed the boundaries of civil engineering and revolutionized the potential of metallic construction.

Lead photo credit : Eiffel Tower, Paris, France. Credit: Chris Karidis, Unsplash