Paris with My Father: A Story of the Second World War

- SUBSCRIBE

- ALREADY SUBSCRIBED?

BECOME A BONJOUR PARIS MEMBER

Gain full access to our collection of over 5,000 articles and bring the City of Light into your life. Just 60 USD per year.

Find out why you should become a member here.

Sign in

Fill in your credentials below.

Even as a child, I had known that my father had been in Paris during WWII. He had a book called Our Leave in Switzerland that featured pictures of American soldiers, but when I realized that none of them were of Dad, I lost my curiosity. In general, Dad never spoke about his experiences, so I did not know that there was something dramatic that I simply did not see. Perhaps, by the time I was born, the war had been over for several years and no longer compelled interest.

When my father died, I was in my own middle age, and as an only child, had to dispose of my parents’ apartment. It took me a long time, for each piece of furniture, each framed picture, every book had memories attached. The absolutely last box I examined, which I found in a closet, contained hundreds of photos, most of which I had seen before – and one I had never seen.

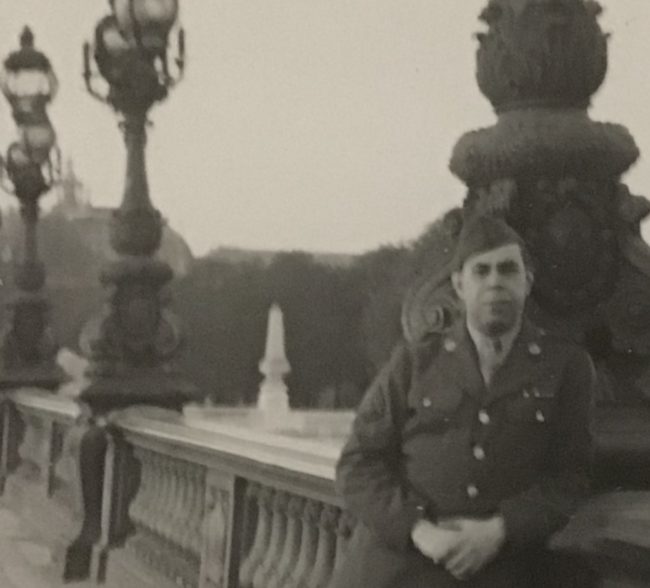

courtesy of Jane S Gabin

Most of the pictures Dad had taken in Paris showed a city happy to be free. People smiled, enjoying the moment. My father and his fellow soldiers were obviously savoring their time in a world capital, their faces reflecting a lack of worry.

But who were these others, obviously civilians, sitting around my father in a domestic setting? There were three women and a child, identified only by last names, pencilled in on the back of the picture by my father. Why were there no men, I wondered. And why didn’t my father ever tell me about these people?

The researcher in me saw a challenge. I checked the last name of the child in the French telephone books I found online. There were many matches. I asked a colleague to help me write a letter in French, saying I was the daughter of the American soldier in the picture – but I did not give his first name. I made copies of the photo and sent one along with the letter to every address on my list. I received only a few responses, all of them negative. Then one day, just before dawn, I got a phone call from a man who was laughing and simultaneously crying my father’s first name.

The author’s father on Pont Alexandre III. Courtesy of Jane S Gabin

The child in the photo taken over 60 years earlier had become a man past 80. A widower, lonely because he had outlived his colleagues, he still resided in Paris. And now that I had found him, I had to meet him. I had several months before I could travel, so I studied the French language, and began to read everything I could about life in Paris during the Occupation. Of course, I had known the rough outlines, but it was never personal before.

When I arrived in Paris, I started to see mementoes of the war and the Occupation everywhere. Mostly I saw plaques, large and small, on buildings, in courtyards, and affixed to the front of every school built before 1940.

I walked the routes my friend and his mother would have taken, I explored the neighborhood where they lived. I visited Drancy, where his father and grandfather had been kept for several months before being sent to Auschwitz, unaware of what was to happen there.

courtesy of Jane S Gabin

One day I went to the house on the rue de Turbigo, where my friend had lived in the days when my father visited. By a stroke of luck, the door was unlocked when I tried it, and so I entered a beautiful tiled hallway. At the foot of the curved stairway inside, I found the concierge polishing the brass handrail. I needed to explain my presence, and began in my hesitant and newly-acquired French, “Pardon, Madame, mais mon père était un soldat américain pendant la seconde guerre mondiale.” This was all that was needed. She smiled and indicated with her hand that I was welcome to look around.

I felt so close to my father then. Of course, I never mentioned any of this to my friend, who says, “I do not wish to talk about the past. Only about today.”

And so we discuss today, and our plans, and what should we get at the Monoprix, and what film shall we see, and which bakery has the best pain au chocolat, and if I am lucky he will tell me more about the past.

Eight years ago, Jane Gabin discovered the identity of a child in a photograph with her father (who was in the US Army) just after the Liberation of Paris. She located him – he is now a retired physician living in the 13th arrondissement- and she comes to Paris each year to see him. Based on his experiences, and the mystery of why her father never wrote to the family after he returned to the States, a family he had been close to, she wrote a novel called The Paris Photo, which can be purchased on Amazon below.

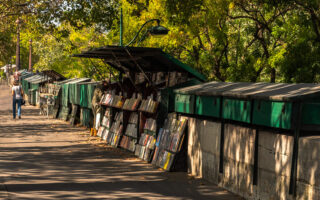

Lead photo credit : courtesy of Jane S Gabin

More in Liberation of Paris, WWII